29 Dec Perspective: Ralph Meyers [1885-1948]

In the first half of the 20th century, Taos was bursting with the artistic genius and creative energy that would transform it into one of the premier art towns in America. And right in the middle of this creative burst was a painter — and a colorful character — named Ralph Meyers.

Meyers wasn’t the most famous of the Taos artists. But he was probably the most versatile. A true Renaissance man, Meyers taught himself how to paint in the house/trading-post/studio he owned on Kit Carson Road, depicting with a singular style and skill the landscapes and lives and culture of the Indians he came to love. In addition, he was the most skilled silversmith in town. He was also a master furniture-maker, helping to define the Spanish-Colonial/Southwestern style. He created intricate beadwork, deerskin clothing, ceremonial pieces and woven goods. Meyers even took a turn at writing. And his legendary parties attracted Taos’ top artists and writers to his living room.

Night after night, Meyers and his young wife, Rowena, entertained artists including Joseph Sharp, Walter Ufer, Buck Dunton, Nicolai Fechin and Ansel Adams; writers including Frank Waters and D.H. Lawrence; and arts patrons including Mabel Dodge Luhan and Millicent Rogers. The conversation was loud and animated, liquor flowed and the raucous merriment often lasted well into the wee hours. In their gatherings, their communications and most importantly, their work, these revelers were defining one of America’s most significant artistic movements. And Ralph Meyers was at the center of it all.

Ralph Meyers was born in 1885 and raised in Denver, Colorado. He had shown an early interest in art, and, taken by the colors and the landscapes of the Southwest, he moved to Taos in 1903. To support his artistic bent, Meyers took a job as a “fire guard” on vacant land. He eventually opened a trading post, and was considered the first white man to openly trade with the Indians of the Taos Pueblo, and to exhibit and sell their crafts at fair prices. Meyers had his first painting exhibition, when he was 32, at the Museum of New Mexico in Santa Fe.

His works eventually came to be exhibited at The Smithsonian, the Museum of Natural History in New York, the Karl May Museum in Germany, the Denver Art Museum and the highly-regarded Millicent Rogers Museum in Taos.

In his book, Serenading the Light, noted art authority David Clemmer wrote this about Ralph Meyers: “Meyers’ work is scarce, but its high quality reveals him as a painter who was part of a second stream of talented Taos artists who worked in the shadow of their more famous contemporaries.” Of those contemporaries, Clemmer noted their probable impact on Meyers. “River Landscape … shows why Leon Gaspard considered him to be a superior colorist. The low horizon line, distant mountains, and large sky suggest a kinship with the work of O.E. Berninghaus, and the paint handling is somewhat reminiscent of that of Walter Ufer. The ‘small gem’ paintings by Meyers are actively sought out and highly appreciated by aficionados of the Taos School.”

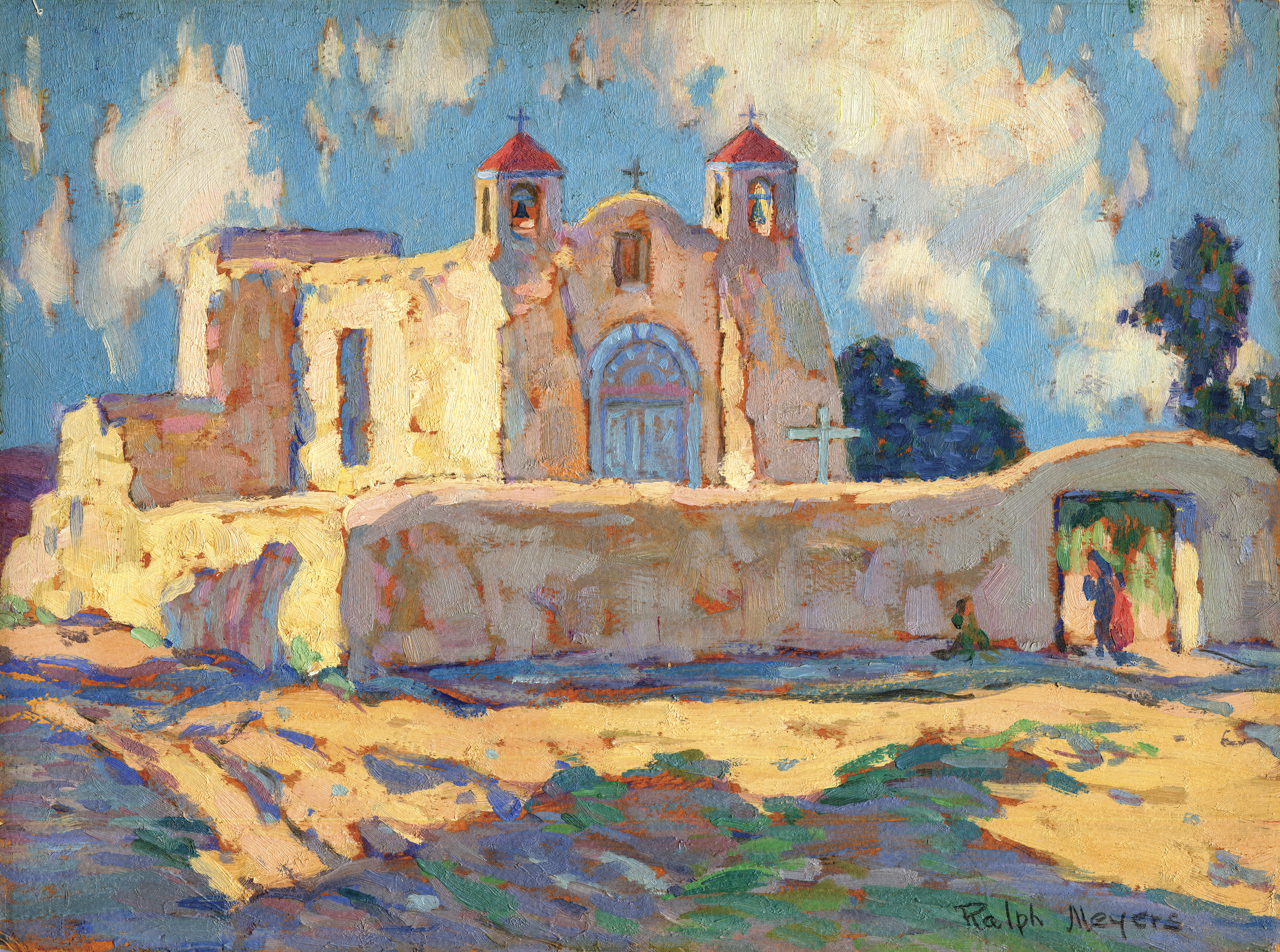

Meyers painted in the Taos style, emphasizing the traditional and the mystical, and the rich colors of the region. He painted what he loved — the majestic mountains and rivers, and his Indian friends on the Taos Pueblo. And his works — Indians On Horseback, In Full Bloom and A Taos Landscape With Stream among them — are still held in high esteem by the Southwestern art community.

“My favorite Ralph Meyers painting is The Studio of the Copper Bell, circa 1915,” says Richard Lampert, co-owner of Zaplin Lampert Gallery in Santa Fe. “Ralph’s flown a bit under the radar at times, because his work is not easy to find. But every time we’ve had one here in the gallery, it’s sold very quickly. He had an interesting Impressionistic style that just seems to connect with the viewer, and draw them in.”

Unfortunately, all the luminaries who knew Ralph Meyers are long since gone. Except for one.

Ralph Meyers’ son, Ouray Meyers, born in 1941, is a noted Southwestern artist in his own right. Ouray Meyers says that, in those days, Taos was still a place where no one looked twice as Ralph rode down the street on his paint pony, wearing a ten-gallon hat. His own talent aside, Ouray is a living legacy to his father. His memories tell the story of a unique artist caught up in the whirl of an extraordinary time in history.

“My Dad was a seeker of knowledge,” Ouray Meyers says today. “He would talk with anyone — old-timers, gambling-hall girls, cowboys, Indians. He was a fourth-grade dropout … but he was always trying to expand his horizons.”

If the company he kept was any indication, Meyers’ horizons were indeed expansive. His son has indelible memories of the great artists who gathered in his parents’ living room night after night. His recollections piece together the incredible community that comprised the Taos School. In his own studio, Ouray identifies his parents’ closest friends, spouting marvelous stories with encyclopedic detail. …

Nicolai Fechin [1881–1955]: Fechin was a Russian émigré who came to Taos and created one of the most astonishing homes in America. Now home to the Taos Art Museum, the exterior is a white adobe structure with vigas sticking out. The interior, however, combines elements of both Southwestern and Russian style, creating an Alice-In-Wonderland-like effect where surprises appear, one after the next. There are hidden doorways; miniature shelves recessed into the walls behind miniature mahogany doors; narrow, winding staircases; secret closets; stone Southwestern fireplaces accented with Russian paintings; obscure alcoves; and Russian samovars sitting atop Pueblo blankets.

“Fechin was a good friend to my dad,” Ouray says. “He came to America to teach art, bringing a 17-year-old bride with him, and ended up as one of the greatest artists in the country. He was a very free spirit — as you can see by his home. And he was so intense when he worked that he was pretty much oblivious to anything else — including his wife, who eventually tired of his rants and walked out.”

Millicent Rogers [1903–1953]: Rogers was the granddaughter of one of the founders of Standard Oil, and became a legendary fashion designer. Yet, she eventually left that gilded world and moved to Taos.

“She used her inheritance for good,” Ouray Meyers says, “donating generously to improve the lives of the Indians on the Taos Pueblo. And she was a passionate campaigner for human rights.”

Rogers’ love of Taos was evident in a letter she wrote to her son, Paul: “Did I ever tell you about the feeling I had a little while ago? Suddenly passing Taos Mountain I felt that I was part of the Earth, so that I felt the sun on my surface and the rain. I felt the stars and the growth of the moon; under me, rivers ran. …”

Ouray reveals that this beautiful, wealthy heiress, who moved comfortably in the arts, fashion and society worlds, was buried in Taos in an Indian blouse, skirt and moccasins, wrapped in a Navajo blanket.

Mabel Dodge Luhan [1879–1962]: A New York writer who left her artist husband behind to move to Taos, Luhan persuaded a lot of painters and writers (including Georgia O’Keeffe and D.H. Lawrence) to move there, as well.

“She’d put me up on the kitchen counter while she was making cinnamon toast,” Ouray Meyers says. “And I can still smell that cinnamon toast today.”

Mabel’s ghost is said to still inhabit her old home on Morada Street — today a B&B — as well as a few other places around Taos.

Frank Waters [1902–1995]: Waters’ The Man Who Killed the Deer (1942) is still considered one of the great American novels of the first half of the 20th century. He and Ralph Meyers were great friends, and Waters used Meyers as the basis for Rudolfo Byers in the book.

“In those days, women had their babies at home,” says Meyers. “My mother was due to give birth to me at six in the evening. So Frank Waters came over to keep my Dad company … and he brought a jug of homemade ‘Taos Lightning’ with him. There was only one problem — I wasn’t born until six the next morning. And by that time, my father and Frank were both too drunk to get up off the floor!”

Joseph Sharp [1859–1953]: Known for his paintings including White Elk, Pueblo Drummer and Crow Camp on the Little Bighorn, Joseph Henry Sharp was a brilliant and well-known Taos artist, in addition to being one of Ralph Meyers’ dear friends.

Ouray remembers Sharp’s hearing impairment. “He wore a contraption on his belt that amplified sounds,” says Meyers. “And you had to speak toward it if you wanted him to hear you.”

And Ouray remembers something else about Sharp, as well.

“I was 7 years old, and I had gone to the movies with my friends,” he says. “When I came out, Joseph Sharp was waiting for me in his car. He told me my dad was dead.”

Eanger Irving Couse [1866–1936]: E.I. Couse may have been the most famous of all the Taos artists. His paintings — The Water Jug and Moonlight Spring among them — often depicted calm landscapes or scenes of solitary contemplation by an Indian.

On the night that Ouray was due to be born, Couse’s daughters sent an Indian — the model for most of his paintings — down to the Meyers’ trading post to report back. And the Indian reported back that “the boy of the dawn has arrived.” The name Ouray, meaning “Pure of Heart,” was taken from an old Ute chief across the Colorado border.

His son is the first to point out that Ralph Meyers was hardly a saint. And, like many creative types, Ralph apparently dealt with some personal demons much of his life. “He was a moody person, particularly later in life,” Ouray Meyers says. “And he drank too much.”

And there was a self-destructive streak, as well. “My Dad, in an alcohol-fueled rage, once set fire to the manuscript of a book he was working on, along with 20 paintings,” says Ouray. “I was very young, but I’ll never forget it. And his relationship with my mother was never the same after that.”

His legacy, however, is without question his art. Ralph Meyers is celebrated for such paintings as Blizzard, depicting a winter storm in an Indian camp; two mounted Indians silhouetted against a stark rock tower in Two Riders and Shiprock; and his peek into the majestic Rio Grande Gorge in Gorge.

“Ralph Meyers fits in among the great names of the Taos artists,” David Clemmer says. “His work compares favorably with the greatest painters in that group. And it’s in high demand today.”

And Meyers is a man who was defined by his friendships and his family. He is buried next to his old friend, Mabel Dodge Luhan, and his tombstone is a 650-year-old petroglyph brought by a Pueblo Indian. On it is a child’s footprint, wandering off; a human handprint; and an eagle’s claw … symbolizing a child wandering off and snatched away by an eagle. A loved one lost.

- Rowena and Ralph Meyers in the front yard of their home/trading post on Kit Carson Road. Photo 1934, Ouray Meyers photo collection

- In front of his trading post, Ralph Meyers (C) embarks on a trading mission into Apache Country with two friends, Ellery Cheetham (L) and Candido Romero (R). Photo 1911, Ouray Meyers photo collection

- “Ranchos” | Oil | 1920

- “River Landscape” | Oil on Canvas | 6 x 16 inches | 1939

- “Santa Clara” | Oil on Canvas | 10 x 14 inches | 1915

- “Blizzard” | Oil | 1912

No Comments