30 May Perspective: The Salmungundi Club

Western art as we know it now was effectively born in the late 19th and early 20th centuries, a period wherein a handful of painters and sculptors took up their tools and trekked west, making pilgrimages to Wyoming, New Mexico and Arizona. Well-educated in the great traditions, they brought with them the visual vocabulary that was then being used in Paris, in London, in New York. Thomas Moran visited Yellowstone in 1871, then the Grand Canyon in 1873. Ernest Blumenschein threw a wheel in Taos in 1898, and E. Irving Couse bumped into Blumenschein, Joseph Henry Sharp and Bert Phillips in France, where he listened to them rave about the desert. Reading the biographies of these extraordinary painters, it soon strikes you that they had at least one thing in common, that the name of a single august club keeps cropping up.

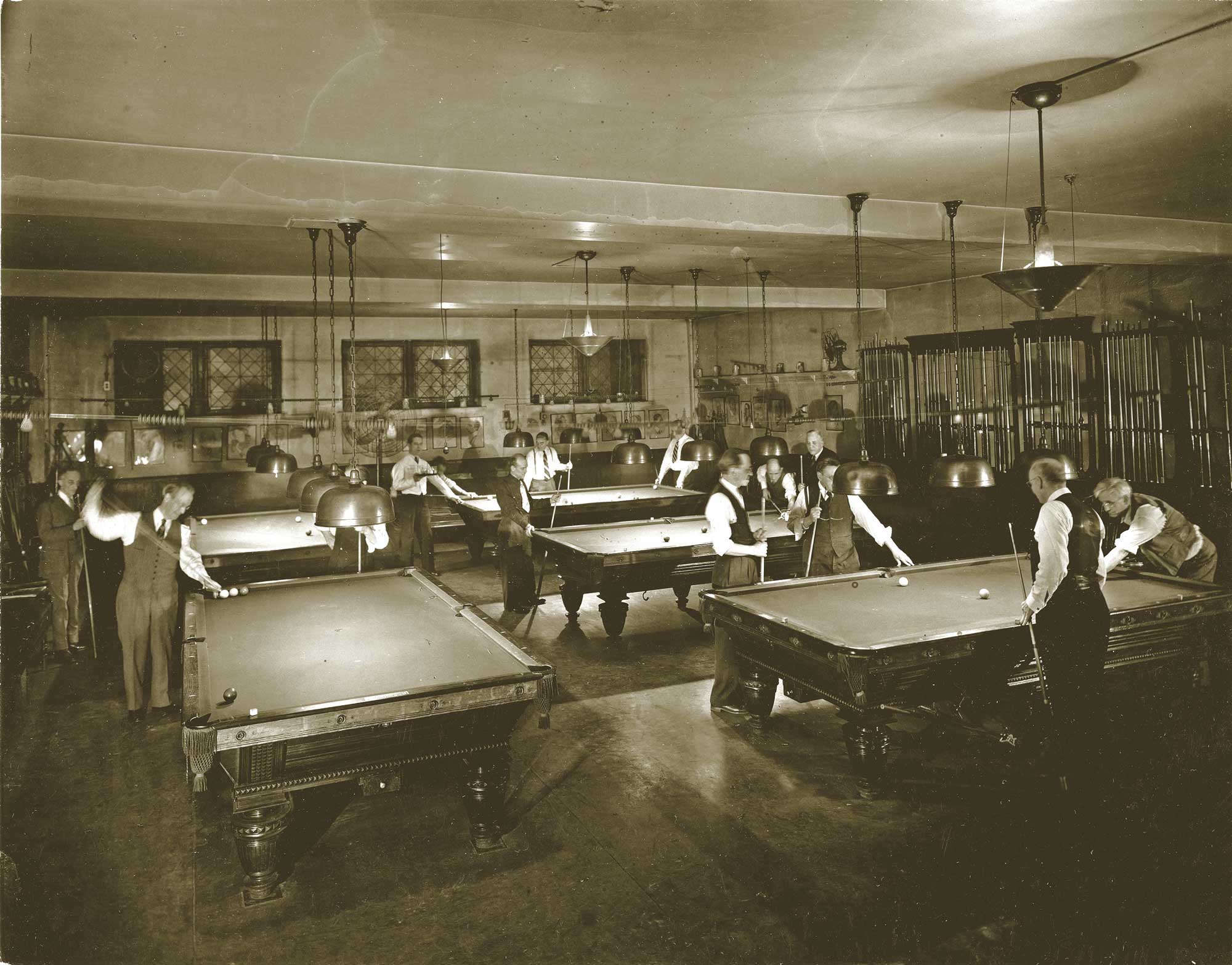

One of the oldest continuing art societies in America, the Salmagundi Club is housed in a beautiful four-story brownstone on Manhattan’s lower Fifth Avenue. An exhibition space, a restaurant, a library, a bar and a billiards room, here is a New York club in a faded tradition, a harkening back to those days when the word salon meant more than a place where you could go to get your hair cut. To tour its exhibition space, to walk up its grand staircase, to browse through the extensive reference library (including a complete set of Catlin’s American Indians) is to see firsthand the foundations of an entire tradition. It’s no great exaggeration to say that this club is where the great art of the West had its common start.

Founded in 1871 as a sketch club by a group of artists associated with the National Academy of design, the fledgling club gradually grew into one of the most influential artist’s groups of the early 20th century. In 1917, after finding a permanent residence in their current antebellum brownstone (the club had previously been housed in the home of sculptor John Rogers), Walter Ufer, Gifford Beal, W.R. Leigh and Ernest Lawson all put their feet up at the club, sipped beer and encouraged each other’s work.

It was an environment that allowed ideas to cross-pollinate, that allowed certain styles and methods to change hands, one to the other. According to Bob Mueller, current chair of the club’s curators committee, “A number of Salmagundi Club members taught the next generation. For instance, Howard Pyle was an early member whose star pupils, N. C. Wyeth and Harvey Dunn, also became members. Dunn passed his knowledge to the great Dean Cornwell, who considered himself a ‘grandpupil’ of Howard Pyle.”

As opposed to today, when most Western artists are natives of their chosen landscapes, in the early 20th century the portraits and vistas of the West were being painted by Easterners, by immigrants who were already part of an established community before they set eyes on Taos or Monterey. The Salmagundi Club saw its walls graced by painters the likes of Blumenschein, E. Irving Couse, Carl Rungius, Edgar Payne, Armin Hansen, William Ritchell and Frank Tenney Johnson. “Blumenschein became a member in 1898,” Mueller said, “and was instrumental in spreading the word about Taos to other artists who eventually gravitated there. Salmagundi was the great meeting ground, the place where the artists would meet and discuss their ideas. I’m sure the club played a vital role in the growth of that colony as it did with those in the East.”

But after this initial, fecund flourishing of art and influence, and as the fashions of the day moved away from Realism and toward abstraction, the club survived but failed to thrive. In recent years, however, the club is seeing a vibrant renaissance. Host to a continuing series of artists workshops and exhibitions, the Salmagundi keeps itself in the public eye, going to great effort to continue its historic contribution to the arts. Among the shows the club sponsors, perhaps the most prestigious, and certainly the most relevant to Western artists, is the annual American Masters Art Exhibition and Sale. (see pg. 132)

Preparing for only its third year, the show has already established a reputation all out of proportion to its youth. Tim Newton, founder and curator of the American Masters exhibit, said that this show has its roots in his friendship with Western artists. “Clyde Aspevig, Tucker Smith, that group of artists with whose work I’m so very familiar, by knowing them, that connection to them, it gave me the courage to create the show that I did.” Western artists that have exhibited at this show include Clyde Aspevig and Carol Guzman, Tim Shinabarger and Bill Anton, Scott Christensen and George Hallmark, Matt Smith and Bill Acheff, John Coleman and Ralph Oberg. And while these artists don’t have the physical proximity to the club that once made it the hub of a community, they are seeing benefits in other ways.

The club’s proceeds from the sale are earmarked for a period restoration of the gallery space, part of the club’s larger goal of bringing the club back to its former glory. Nevertheless, despite their fundraising needs, they are careful to keep the artists’ concerns first. Newton said, “Artists get 75 percent of every sale, which is very high. The club receives only 25 percent. Everybody knows artists are struggling nowadays. This is a way we can lend a hand. And for them to be able to hang their work on Fifth Avenue, in a venue where Rungius and Frank Tenney Johnson displayed, for them to follow in those footsteps, it seems like a great opportunity. And it’s wonderful for New York to have a chance to see some fabulous Realism. My desire ultimately is that it will be the best art show in America.”

Lining the second floor library, just above the bookshelves, the club displays more than 100 artists’ palettes, the largest collection of its kind in America. To sit at the long table and consider the rows of smeared colors (some dating back more than a century), the occasional faded doodle under a puddle of hardened paint, is to see the effort behind the art, the tactile history behind an untold number of masterpieces. It’s a display that is, in a way, symbolic of the club itself. A collection of gestures that demonstrates a sense of community, an aggregate of artists that collectively helped each one become more than they might have otherwise been. With the help of Newton, Mueller, club president Claudia Seymour, a loyal staff and board, the Salmagundi Club is well on its way to reproducing that golden era.

“My ambition,” Newton said, “is to create an awareness of what a gem the Club really is. It’s a national treasure.”

Allen Morris Jones is the author of, among other books, A Quiet Place of Violence: Hunting and Ethics in the Missouri River Breaks, and a novel, Last Year’s River. He is also the owner and principal editor of www.manuscriptmedics.com.

- Salmagundi Club Exterior

- The main gallery set for an awards dinner, n.d.

- Charles Shepard Chapman | The Wolf | Oil on Canvas, 14 x 14 inches, n.d.

- Frank Desch, La Robe de Boudoir, Oil on Canvas, 36 x 30 inches, c.1923

- Emil Carlsen, Still Life with Copper Pan, Oil on Canvas, 32 x 30 inches, 1901

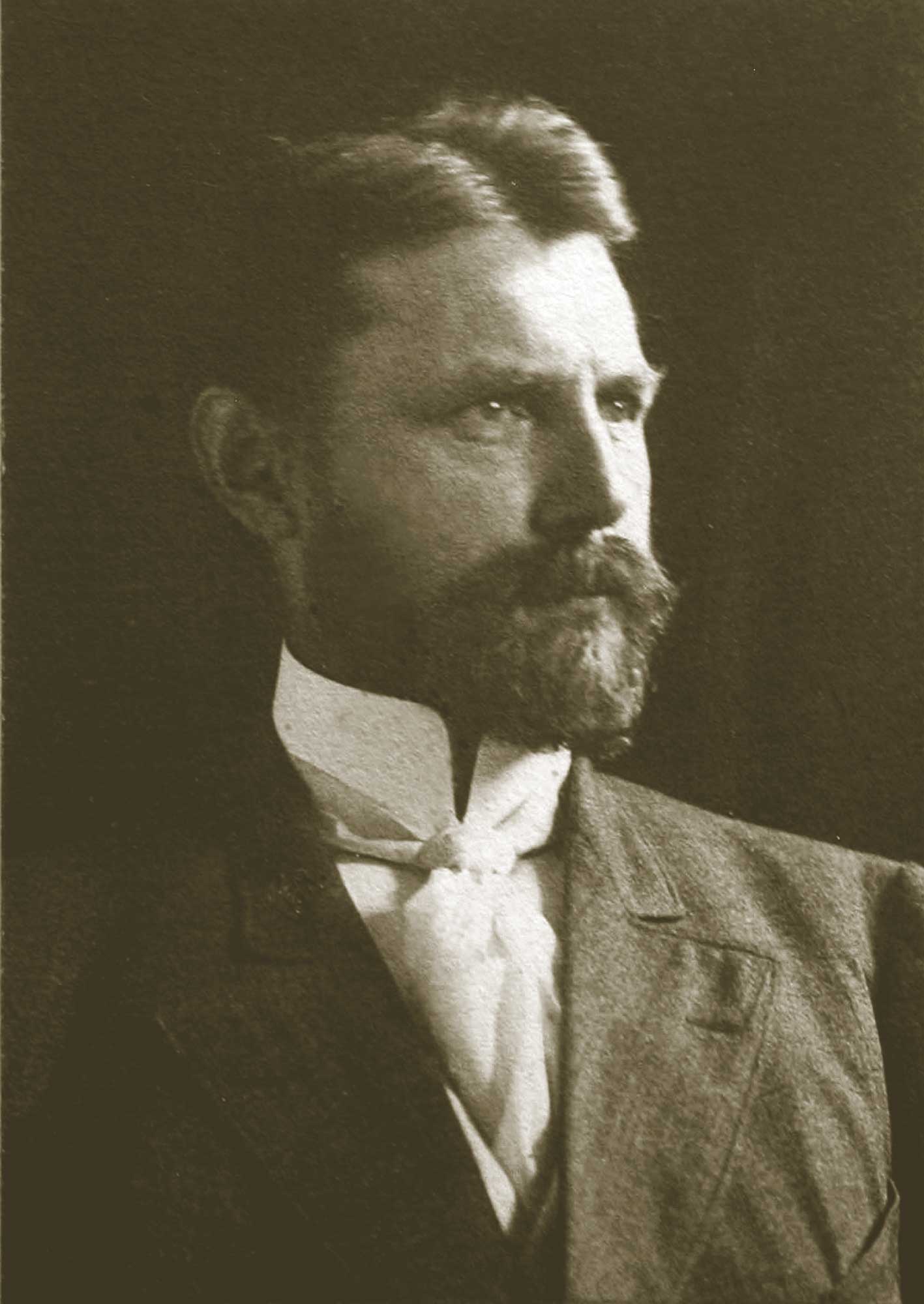

- Edward Potthast

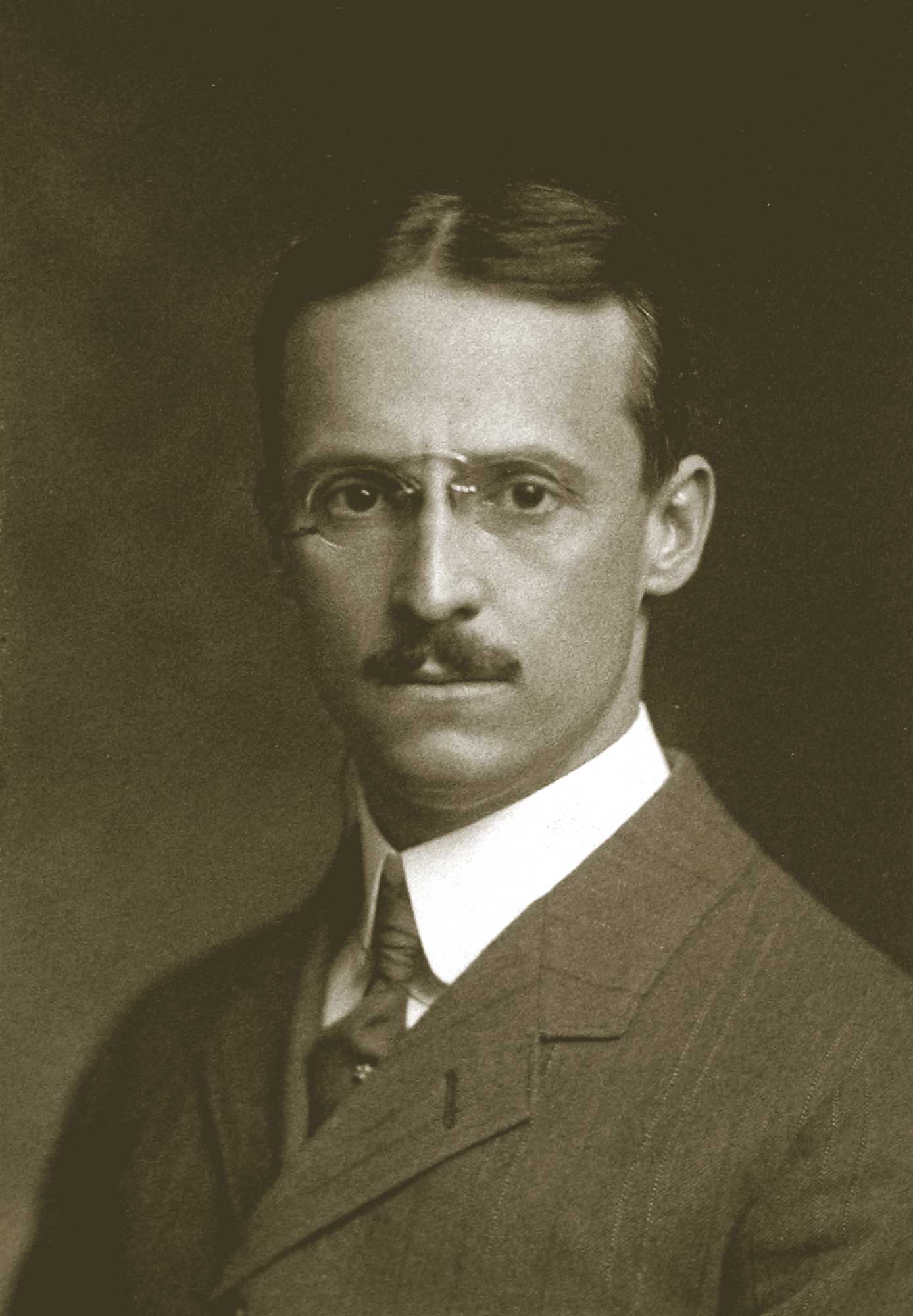

- Ernest Blumenschein

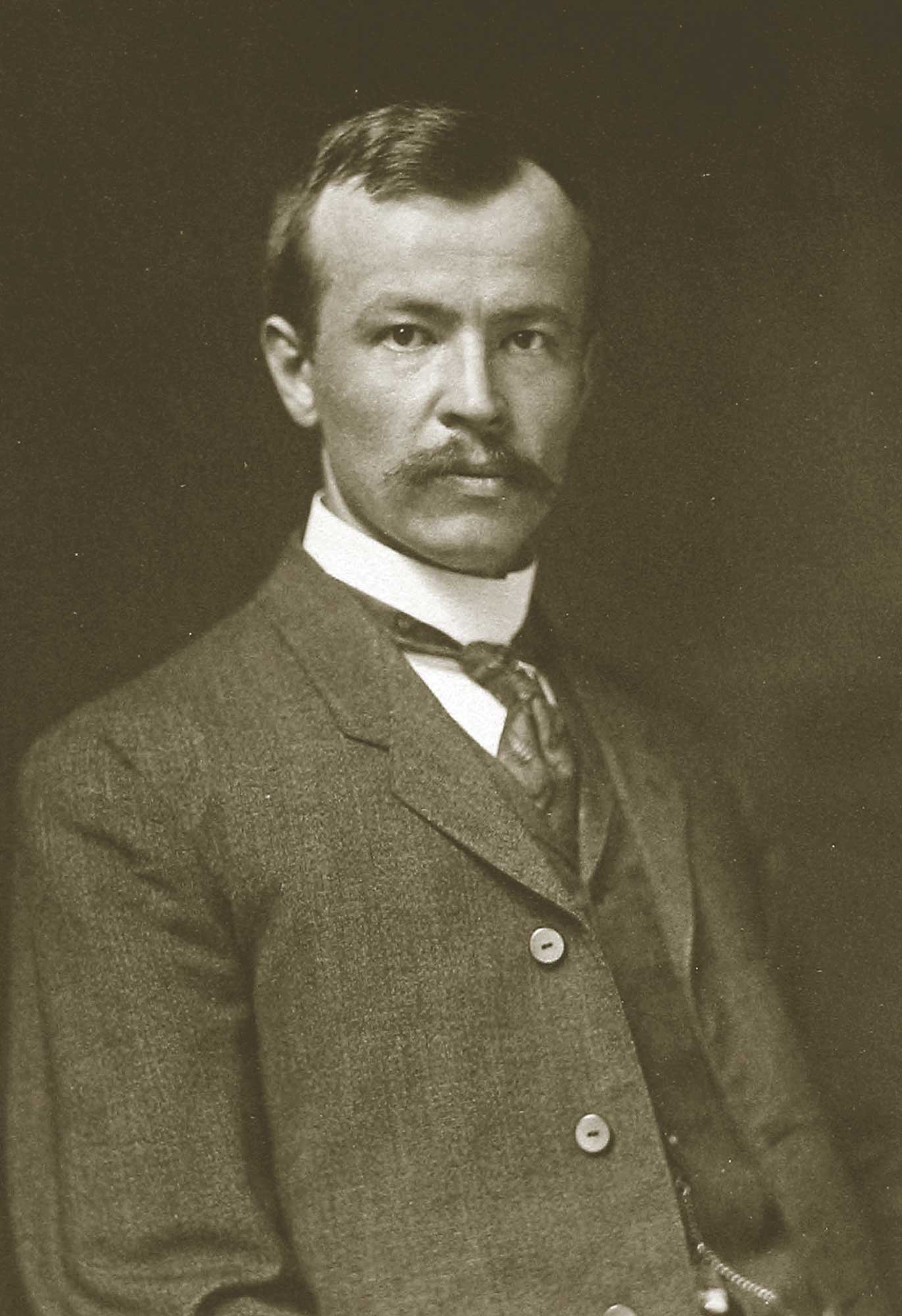

- Carl Rungius

- E. Irving Couse

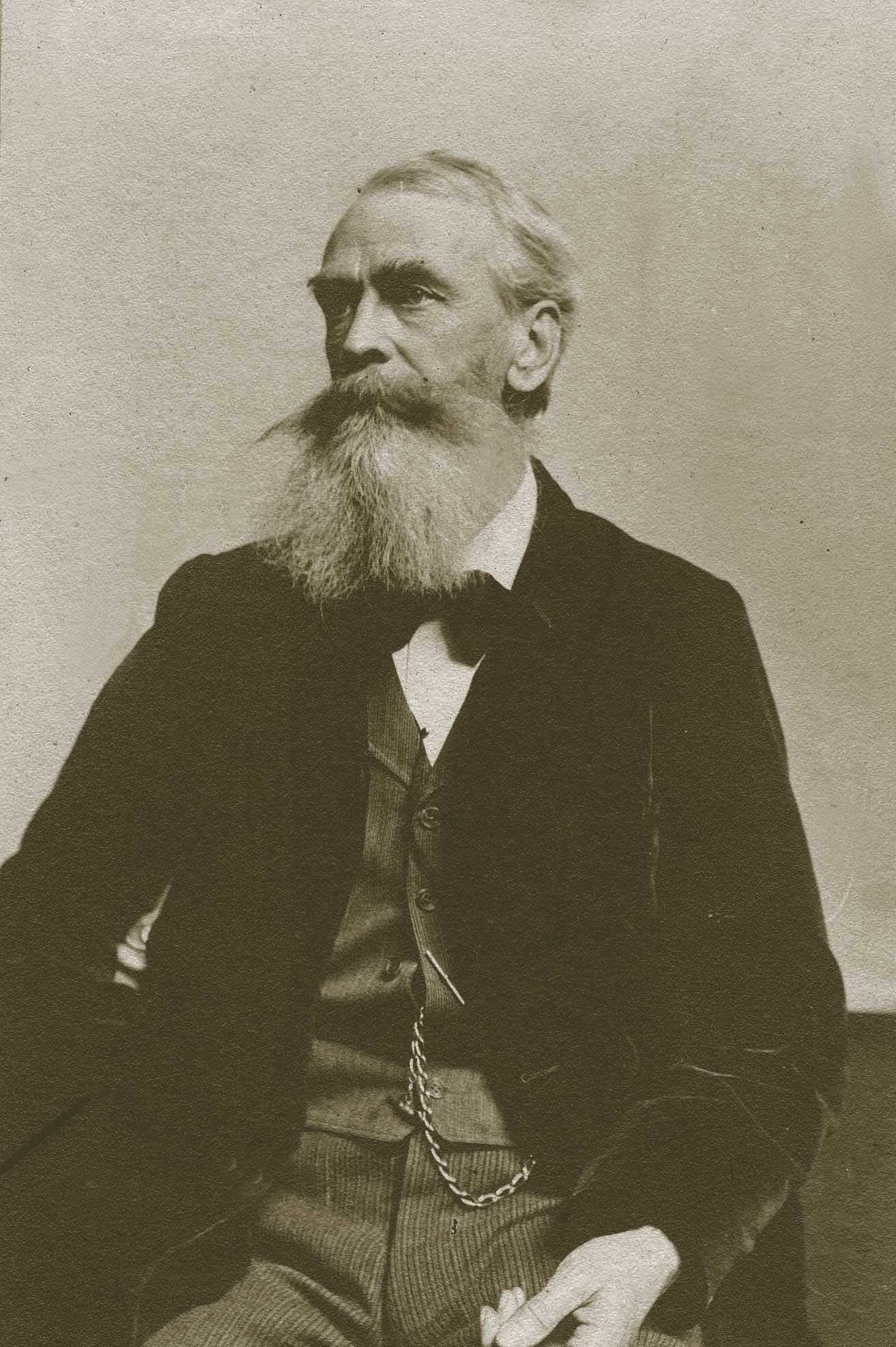

- Thomas Moran

- William Ritschel

- Salmagundi staircase by James Dow

- Salmagundi parlor by James Dow

- A friendly gathering in the Salmagundi Bar, c. 1945

- Hugh Bolton Jones | Quiet Stream | Oil on Panel, 20 x 30 inches, c. 1896

No Comments