04 Aug Perspective: The Taos Society of Artists

When New York and Chicago art critics got their first look at paintings by members of the Taos Society of Artists, formed in 1915, some described the work as unrealistic and overly romanticized. The colors were radically vivid, the subject matter exotically quaint, the light too intense. What these modern, urban critics couldn’t know was that this was indeed what northern New Mexico looked like, with its vast, sun-washed landscape, earthen architecture and ancient Pueblo and Hispanic cultures.

Art historian Virginia Couse Leavitt, granddaughter of Taos Society member E. Irving Couse [1866 – 1936], remembers living with her grandfather for her first six years. “When I was a child growing up in Taos, everything looked like those paintings,” she says. There were blanket-draped Pueblo Indians on horseback under golden aspens; Hispanic families in colorful fiesta dress; majestic mountains looming under dramatic skies. These were images that enraptured the Society’s founders and brought out and nurtured the best of their artistic skills. In turn, the Taos Society of Artists introduced to the world what would become the historic Taos Art Colony and current-day arts destination, helping put what was a tiny mountain community on the international map.

This year marks the 100th anniversary of the Society’s founding, a milestone being celebrated through exhibitions, lectures and performances throughout the year at venues around Taos.

What began in 1898 with a broken wagon wheel, according to the fabled account, blossomed into an economic alliance of painters consisting first of six, and eventually 12 full members: Bert Geer Phillips, Ernest Leonard Blumenschein, Joseph Henry Sharp, E. Irving Couse, Oscar E. Berninghaus, W. Herbert Dunton, Kenneth Adams, Walter Ufer, Victor Higgins, E. Martin Hennings, Catharine Critcher — the sole female member — and Julius Rolshoven. When the Society disbanded in 1927, there were also a handful of associate and honorary members.

While Blumenschein and Phillips became enchanted with Taos in the spring of 1898, the genesis of the Taos Society of Artists predates its founding by more than 10 years. In 1893, Joseph Henry Sharp [1859–1953], already an established painter and illustrator, traveled from his Cincinnati home to Taos on an illustration assignment for Harper’s Weekly. The following year Sharp continued his studies at the Academie Julian in Paris. There he became acquainted with two younger art students, Phillips [1868 – 1956] and Blumenschein [1874–1960], and enthusiastically related to them his impressions of New Mexico.

The younger artists, who shared a studio in New York City, needed to see for themselves. In 1898 they traveled to Denver and purchased supplies for a painting trip by horse-drawn wagon through New Mexico to Mexico. Twenty miles north of Taos, the rugged terrain caused one of the wagon’s wheels to break. The men flipped a three-dollar gold piece to decide who would carry the heavy wooden wheel on horseback the rest of the way to Taos to be repaired, and who would stay with the wagon.

Blumenschein rode to Taos. Yet before he even reached the village, he knew his way of seeing the landscape had changed. “My destiny was being decided as I squirmed and cursed while urging the bronco through those many miles of sagebrush,” he later wrote. “I realized I was getting my own impressions from nature, seeing it for the first time with my own eyes, uninfluenced by the art of any man.”

This last point was significant. After three months, Blumenschein returned to New York City and Phillips remained in Taos. As they began corresponding about forming an art colony, the idea of a uniquely American art had become increasingly compelling. Along with Sharp, they envisioned employing their academic training on fresh, distinctly non-European subjects far removed from anything they had painted before.

Other factors converged to draw to Taos those painters who would travel there for summers of painting and eventually become Society members. By 1915 the horrors of World War I were taking place in Europe. Industrialized cities were becoming increasingly crowded, dirty and alienated from nature. At the same time, anthropologists were helping reshape the perception of Native Americans, especially in the Southwest, from savages to a dignified, peaceful people, skilled in sophisticated age-old arts.

With its ancient, agrarian culture and beautiful pottery, textiles and baskets, Taos Pueblo symbolized for many an enviably simple and sane way of life, in harmony with the land. This vision was especially compelling to painters who lived and had studied in East Coast cities and Europe. Their Taos studios, in old adobe houses, were soon filled with collections of Indian and Hispanic artifacts and crafts.

“I think America was ready for Taos, and the Taos Society of Artists in 1915 gave it to them,” observes Dean Porter, director emeritus of The Snite Museum of Art at Notre Dame University in Indiana. Porter, who has studied the Society since the mid-1970s, is the author of Taos Artists and Their Patrons, 1898-1950 and an important book on Victor Higgins, and is working with Stephen Good on a monograph on Walter Ufer.

Joining the Taos Society of Artists meant meeting strict requirements and being voted in by existing members. Artists had to have painted in Taos for three consecutive years, which for most meant only summers until electricity, running water and other comforts made life in the remote village sufficiently appealing for the artists and their wives to stay year-round. Prospective members had to be recognized as established artists who had exhibited in respected galleries, museums or salons. With this level of professionalism the members were able to achieve their primary objective as a group: to promote their Taos paintings and introduce their work to the museum and gallery world, and to the American public.

Other than the artists’ studios, there was almost nowhere in Taos in the early days to show their art, and virtually no collectors. So the Society arranged a circuit-traveling exhibition, each year shipping a selection of paintings to New York City, St. Louis, Chicago and other cities, and often to the Museum of Fine Arts in Santa Fe following its establishment in 1917. After the Harwood Foundation (now The Harwood Museum of Art) opened in Taos in 1923, the Foundation’s small gallery space became another of the earliest New Mexico venues for Society artists, says Harwood Museum Director Susan Longhenry.

While sales at stops on the traveling exhibitions were never strong — many times the group was lucky to sell a total of a half-dozen paintings during the entire circuit — the effort led to solo gallery exhibitions for a number of the artists. Individual members, especially Couse, Blumenschein, Higgins and Ufer, also did well in competitive juried exhibitions at preeminent museums between 1917 and 1926, taking top prizes at the Museum of Modern Art in New York, National Academy of Design in New York, the Chicago Art Institute and others. Today, paintings by some Taos Society artists bring more than $1 million at major auction houses.

In the village of Taos in the early 20th century, where European-Americans were a distinct minority after Taos Pueblo Indians and Hispanics, Taos Society artists became an important part of the community. They enjoyed each other’s company socially, but did not paint together; they were a “loose federation of individuals,” as Porter puts it.

In the late 1920s, that alliance lost its footing as economic conditions faltered and tensions among members arose, including Blumenschein’s cofounding of another group, the more stylistically progressive New Mexico Painters. When the Society disbanded in 1927, it had “served its purpose,” Couse Leavitt says. “Its members were well known by then and were in demand for solo exhibitions.”

Although the Taos Society members worked in a variety of representational styles, they shared, either directly or indirectly, the influence of the academic training of the day, with a strong focus on mastery of the human form. From there, Sharp, Couse, Phillips and others continued in a conservative approach, while Blumenschein, Higgins and Ufer moved in more experimental and even Modernist directions. Collectively, their impact on later generations of artists was not so much related to style as it was the expression and dissemination of “a feeling about Taos, that there was something special about this place,” Porter says.

That attitude, along with later recruiting efforts by arts patron Mabel Dodge Luhan, the Santa Fe Railway, Fred Harvey and others, brought increasing numbers of artists and visitors to New Mexico and produced a flourishing art scene, the allure of which remains strong.

“On a larger scale,” Couse Leavitt says, “it is now recognized that the Taos Society of Artists played an important part in the history of American art in the early 20th century by promoting a truly American art through depictions of new landscapes and subjects, using the brilliant light and color of the Southwest. This was a breath of fresh air at the time. The quality and integrity of their work gives it lasting appeal to collectors today.”

Gussie Fauntleroy (gussie7@fairpoint.net), based in southern Colorado, has been writing about art, architecture, design and other subjects for 25 years. She contributes regularly to regional and national magazines and is the author of three books on visual artists.

- Kenneth Adams, “Ranchos de Taos Church–Moonlight” | Private collection

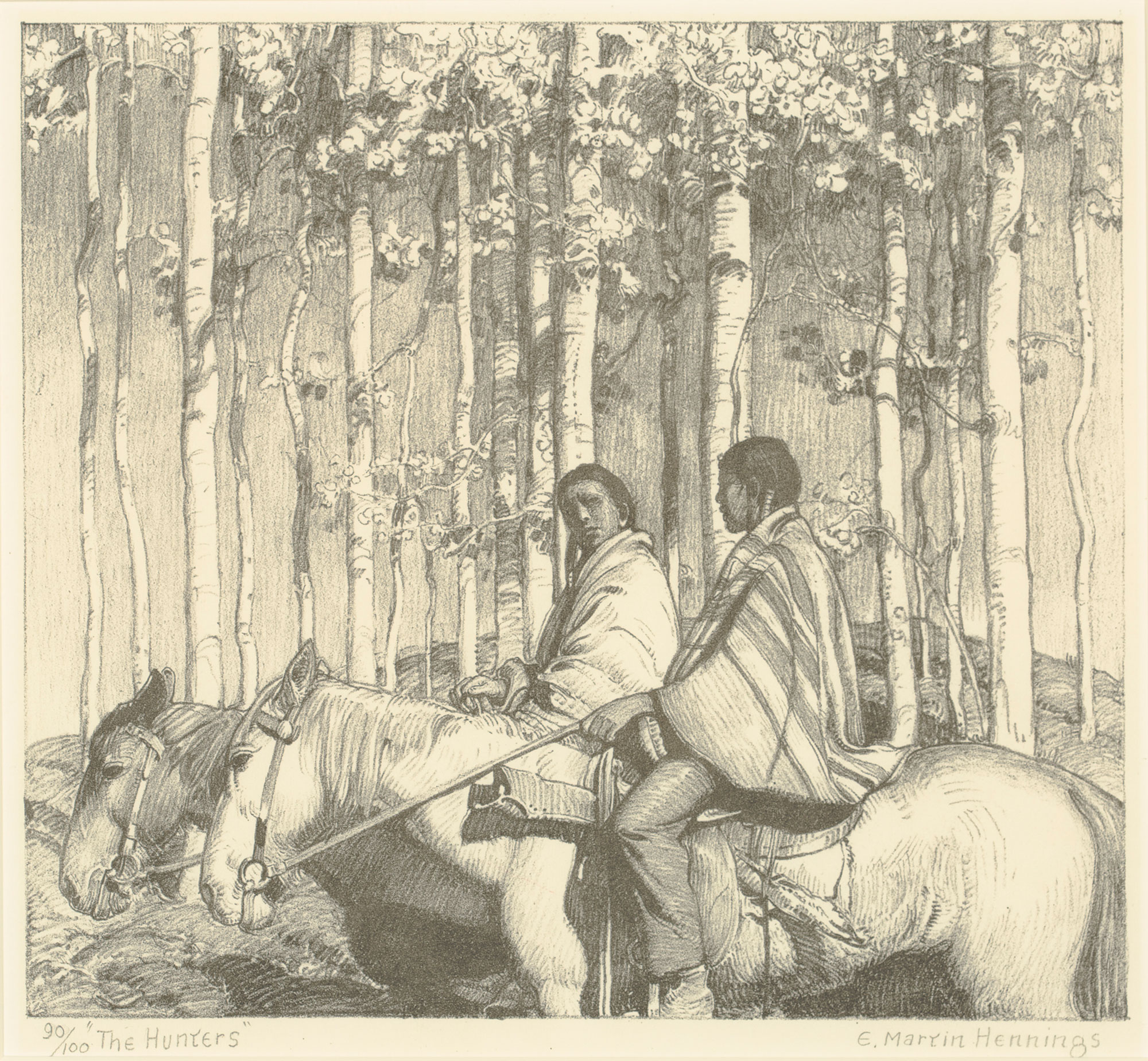

- E. Martin Hennings | “The Hunters” | Lithograph | 15.75 x 16.375 inches (framed) | Gift of Van Deren and Joan Coke in memory of Caroline Lee, Collection of The Harwood Museum of Art

- Oscar E. Berninghaus, “Haytime and Showers” | Oil on Canvas | 35 x 40 inches | c. 1940 | Private Collection

- Ernest L. Blumenschein, “Sandia Mountains” | Oil on Canvas | 21 x 25 inches | c. 1950 | Private Collection

- E. Martin Hennings, “Tending the Flock” | Oil Painting

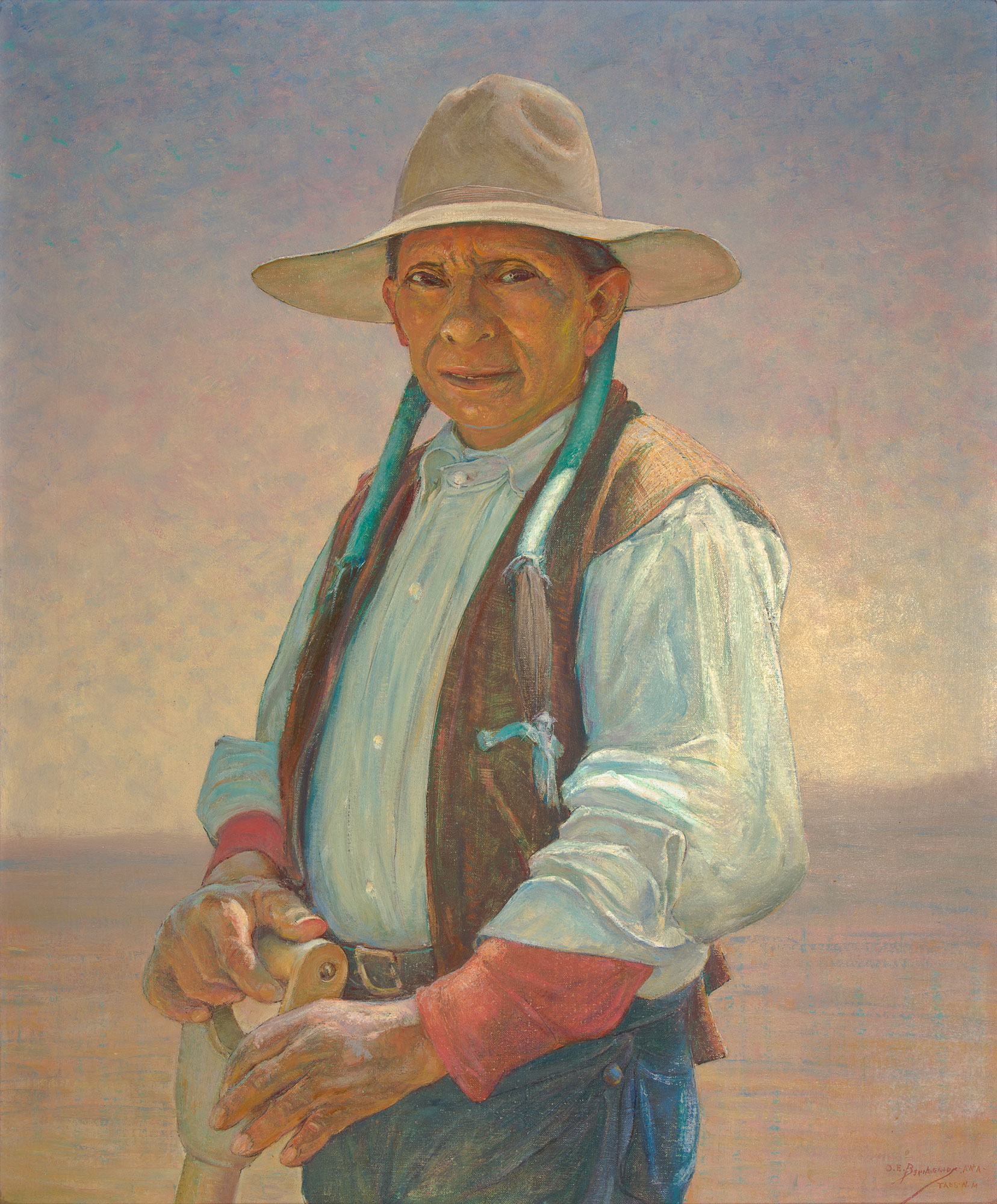

- Oscar E. Berninghaus, “Little Joe” | Oil on Canvas | 30 x 25 inches | 1941 | Private Collection

- Joseph H. Sharp, “Apache Plume” | Oil on Canvas | 20 x 24 inches | Collection of Stephanie Bennett-Smith and Orin Smith

No Comments