24 Jul Perspective: Willard Clark [1910-1992]

Spend any time in Santa Fe and you’re likely to come across the work of Willard Clark. In fact his images are so ingrained in the culture of the town, his vignettes and scenes seem to be the indigenous graphic style, rather than the work of a single artist. Clark’s influence is seen everywhere in town: The unique woodcuts and etchings that still adorn local menus and advertisements throughout the city feel quintessentially “Santa Fe,” nearly 20 years after his death.

Willard Clark was born in Massachusetts in 1910, though he spent most of his childhood in Argentina, where his father was the regional president of General Motors. On his way to California, in 1928, Clark stopped in Santa Fe, and like so many artists before and since, was captivated by the landscape and culture of the town. He never left. Sensing a need, he opened a commercial printing shop, and quickly became one of the town’s premier graphic artists, complementing letterheads and business cards with images of burros and cacti and men in sombreros.

These simple figures captured the essence of “Old Santa Fe,” and lent a stylized regional character to the work. His illustrations were done in wood-block, a technique that was even then fairly outdated in commercial work. Clark loved using his hands, and quickly took to the demanding medium, largely on his own, going so far as to make his own tools. He ground his own inks, learning from master Gustave Baumann, who had himself been ensnared by Santa Fe’s charms 10 years earlier.

The attention to detail manifested in Clark’s carvings, ink preparation and paper selection was matched by the care he took in the printing process itself. He eschewed state-of-the-art automated presses in favor of hand-fed machines that he could control precisely by hand and eye. He would play with every detail, compensating where necessary for uneven, handmade papers, even changing the angles at which he inked the blocks to achieve desired effects.

The excellence of his craft in a city with centuries of tradition in handmade things did not go unnoticed, and the artistic scenes Clark produced became more and more prominent in his work, spilling beyond the margins to become the centerpieces of his printing. His reputation spread throughout the Southwest and clients included the Santa Fe Railroad and La Fonda Hotel, for whom Clark printed the menu daily. He also had to frequently reprint La Fonda’s “Do Not Disturb” signs, featuring a man and a burro asleep beneath a tree, as visitors often took them as souvenirs. In addition, Clark designed many of the advertisements for the local craft shops, which were rapidly becoming tourist destinations for those seeking Indian and Hispanic folk art.

As Santa Fe grew into a world-class center for indigenous arts and antiquities, Clark, with his street scenes featuring adobe buildings, wood-laden burros and artisans in native attire, was establishing a “look” for the city itself, both ancient and modern. His style, simple and unpretentious, was timeless, conveying in the fewest lines possible the iconographic elements of his beloved town. Black Cross on Hill (1935) is typical of his work: an almost glyphic depiction of a man with a sombrero on a burro amidst a landscape of variegated wood-block textures. Not unlike his chosen home, Clark’s work was marked by humility and industriousness, quiet and simplicity.

Another distinguishing feature of Clark’s commercial work was his use of the Neuland and Neuland Incised type-faces. Ubiquitous in his prints, notably the cover of the brochure for the Super Chief of the Santa Fe Railroad (1937), they have become the unofficial font of Santa Fe, spread nationally by The Santa Fe Tobacco Company’s American Spirit packaging, and in use today in signage and local publications.

The wood block scenes he carved — from simple one-color silhouettes to elaborate multi-color scenes — soon began to have a life of their own, removed from the typographic milieu of commercial work. His detail and craftsmanship gave his prints a certain “completeness” despite their often small size. Even in simple designs, with only three colors, his skill in overlaying his hand-mixed color, his seamless registration and his loving attention to each individual print run made for exquisitely realized works. A later work, Clouds (1986), shows how using only black, blue and an earthy red as glazes, he was able to intermingle and overlay them to create a storm sky with depth and richness. Clark would extricate favorite images and use them for book illustrations and prints in their own right. The work of Clark’s Studio and affiliated publishers was well-known across the country, appearing in book arts journals and such publications as Scribner’s Magazine.

Despite his success, the influx of larger printing businesses into New Mexico and the onset of World War II led Clark to sell out his business and go to work at the Los Alamos National Laboratory as a machinist. While he continued to paint and started designing jewelry, he would not print again for another 40 years. Had Clark’s story ended there, he would still be remembered for establishing a visual style as evocative of place and time as Hogarth’s etchings of 18th-century London.

In the early 1980s, Pam Smith of the Print Shop of The Palace of the Governors in Santa Fe became enchanted with the prints she discovered from the 1930s and ’40s, and sought out the retired Clark, encouraging him to resume his work. Delighted to find there was still interest, Clark did just that. He had saved many of the fine art prints he produced in the ’30s, and more importantly, he had carefully stowed away all the original blocks. Purchasing a 1910 Potter proof press, and taking on his grandson, Kevin Ryan, as an apprentice, Willard Clark was once again a printmaker.

Some of the blocks he saved had never been printed, waiting 40 years from inception to completion. And not only did he start printing again, he started making blocks again. Though in his 70s, Clark’s work as a precision machinist at Los Alamos and his jewelry making had kept his hands nimble. In fact, he gravitated more in this period to wood engraving, producing works in the stubborn end-grain of various hardwoods with up to 130 lines per inch. Starry Night (1987) contains all of his familiar forms rendered in delicate lines. These moody black-and-white images, together with the multi-color woodblocks resurrected from his past, established a portfolio of more than 150 prints that he made available to visitors at his home studio.

“Starting in 1984 or ’85, Pam would come over to my grandfather’s studio and they would have lunch and discuss many things. But, she got him excited about the woodcuts again,” recalls Ryan.

Meanwhile his work was finding new life. Pam Smith featured him in a book arts show at The Palace of the Governors, even inviting him to design the poster. Old works were showing up in magazines, sometimes uncredited, as they had the feel of “public domain.” And Clark was asked to design book covers, notably for Santa Fe and Taos: The Writers Era, 1916–1941, as his work personified the age. For a city so defined by its heritage, Clark had become a part of that heritage. The bohemian early 20th century was another layer of history gone but still present in Santa Fe, and Willard Clark was once again in high demand to depict it.

In 1985, Clark decided to create his own homage to the Santa Fe he had found as a young man. He began Recuerdos de Santa Fe: 1928 – 1943, a series of 46 brief word sketches of life in this simpler time, each illustrated with a wood engraving. With the help of his grandson, Clark hand-printed and bound the first 50 of the edition before his health gave out. Ryan, now very accomplished in the handiworks he learned at his grandfather’s knee, finished binding the original edition of 100. In its trade edition, Recuerdos or Remembrances of Santa Fe has become a local classic, embodying for many what it is that makes Santa Fe so special.

Willard Clark died in 1992, leaving his follow-up to Recuerdos, The Simple Life, unfinished, though some engravings were completed. These pieces — his last works, done at age 82 — show the same attention to detail and whimsical nostalgia as his earlier works.

“Late in his life, Grandpa worked more on wood engravings. He enjoyed the process and spent many hours looking through books filled with other artists’ engravings,” explained Ryan.

Since his death, Clark’s work has become highly collectible, not just in Santa Fe, but to aficionados of 20th-century American printmaking. His original prints are rarely parted with, most on the market coming from his estate, and can command up to $10,000 each. Clark, who always maintained that he was just a humble craftsman, rarely signed his work, and such pieces are especially valuable. Kevin Ryan, who controls the Clark’s Studio estate, has continued to make prints from the original blocks his grandfather left behind, though because of the ephemeral nature of the materials used, only small runs are produced. Having learned from Clark himself, and using the old techniques and hands-on care passed on to him, Ryan’s restrikes admirably maintain the standards and feel of the originals. It is through these works, displayed in select galleries and shops in the city, as well as in the posters and gift cards and graphic sensibility seen throughout the town, that Willard Clark, chronicler of a romantic era, stays alive and ever relevant.

- This doorhanger was made for La Fonda Hotel in Santa Fe in the 1930s. A woodblock print on heavy paper, 4.5 x 6 inches

- “Simple Life #2” | Woodcut (restrike) | 6.5 x 3.5 inches | circa 1992

- “Black Cross on Hill” | Woodcut (restrike) | 3.5 x 3 inches | circa 1935

- “Simple Life #2” | Woodcut (restrike) | 6.5 x 3.5 inches | circa 1992

- “Starry Night” | Woodcut (restrike) | 2.5 x 5 inches | circa 1987

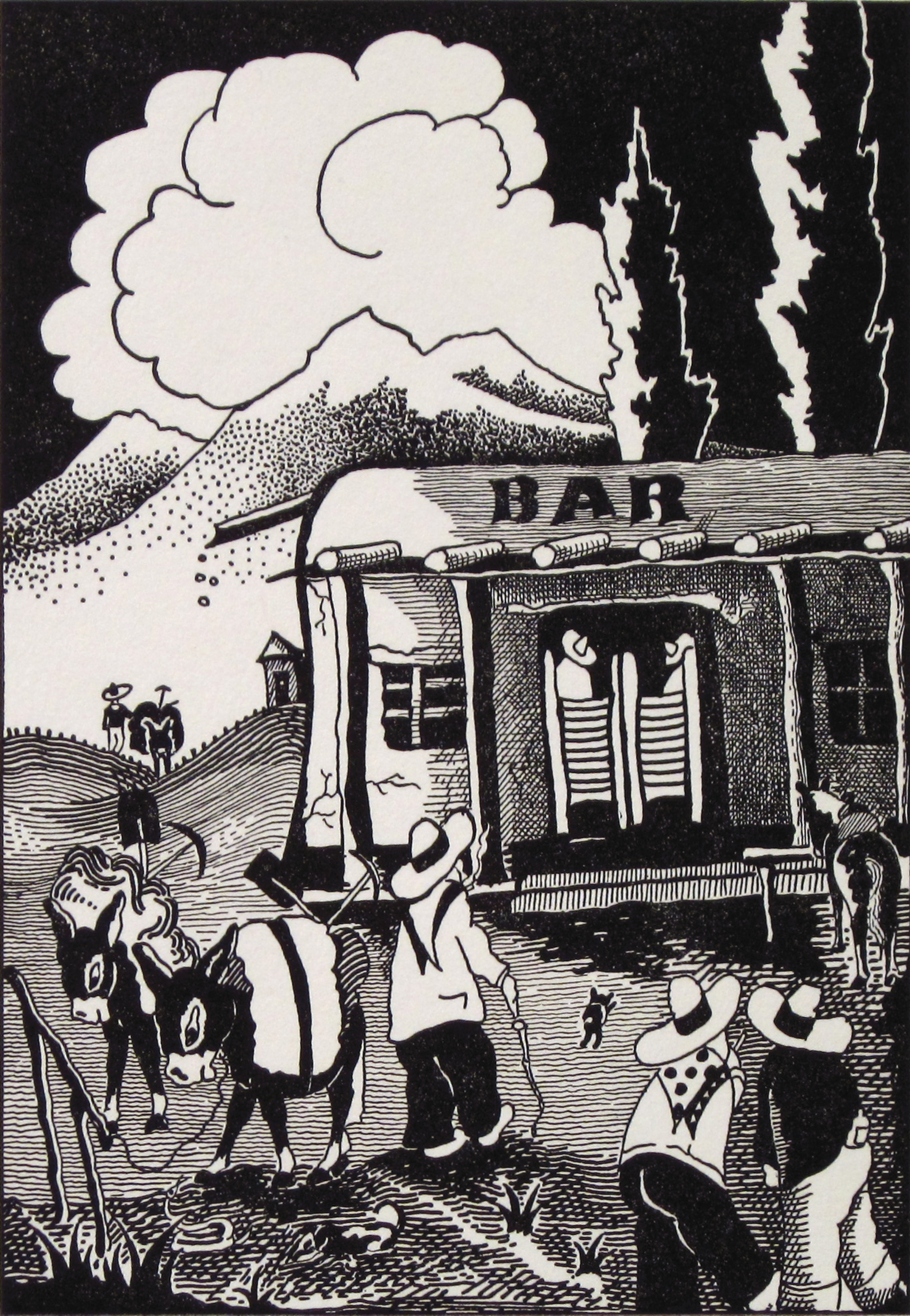

- “Bar” | Etching (restrike) | 6.5 x 4.5 inches | circa 1935

No Comments