09 Jun Rendering: Collision, Overland Partners

At the front entry of Overland Partners, there are three steel gates that interrupt the red brick of the building, a recently renovated 1918 warehouse located in San Antonio’s art district. Each gate is covered in dozens of circles with varying circumferences. And if you stand at a distance to take in the full perspective, a pattern begins to emerge — a methodology behind what otherwise appears as a series of randomly cut shapes in a sheet of steel.

The gates replicate a Jackson Pollock painting, explains architect Timothy Blonkvist, a principal at Overland. Pollock’s work was digitized, enlarged to four times its original size and turned into a pattern with each circle representing a drop of paint. The smaller dots will eventually be filled in with translucent acrylic material in various hues.

“So, the art has been transformed into architecture. Or is it still art? What is it? A gate or [a version of] a painting on the wall?” Blonkvist asks. This question, of defining the border between art and architecture, is one that the architecture firm often addresses. And as the front entry to a firm that tends to blur these boundaries daily, there couldn’t be a more appropriate primer for the ideas formed inside.

But Overland’s quest to curate artful structures goes well beyond aesthetics. Clearly articulated in the firm’s mission statement — “Modeling how we should live and influencing the world through the practice of architecture” — Overland Partners is value-driven rather than motivated by a particular stylistic achievement. Their design process emphasizes collaboration with clients, “engaging people at an intellectual and emotional level,” that often results in buildings that are well loved.

“We can either have the idea that our clients are our patrons — a funding source for our creativity — and they can buy our work of art that we create, or they are our co-creator. … And what we realize is, all people are creative.

Inevitably born creative and sometime during our life it’s squelched and we’re told, ‘Don’t do this, do that instead.’ But when someone is invited into that process and guided, they get really excited when they see their thoughts and ideas come to life. They take ownership,” says Blonkvist. “Our clients could be more like patrons that pay us to do one thing repeatedly, or we can take the attitude of being the servant rather than the artist.”

Established in 1987, Overland Partners was founded by four college friends: Richard Archer, Timothy Blonkvist, Robert Schmidt and Madison Smith, who each went in different directions after earning architecture degrees from the University of Texas at Austin, gaining valuable experience in architecture, construction and real estate development. Robert Schmidt left in 2012, but remains in close contact with Overland, and the firm subsequently acquired four additional principals: Bob Shemwell, James Andrews, Jim Shelton and Becky Rathburn. With an ever-expanding list of clients, Overland grew from 40 to 60 employees in the last year, with representation from across the world, including Zimbabwe, Italy, India, Wales and China.

Bringing a wide range of talents and global knowledge about architecture, Overland has designed projects throughout the United States, Europe, China, India and Saudi Arabia. The award-winning firm has been recognized for its design excellence with some 150 awards, from local to international.

The scope of the firm’s work ranges from art museums to Fortune 500 headquarters, homeless shelters, libraries, university buildings, luxury private homes and ski lodges. The common thread in each project is the intent to create an artful setting and narrative structure that “unlocks the embedded potential” of a landscape and the client’s wishes.

“This is a deeply rooted philosophy,” offers Blonkvist. “There’s always more there if you are willing to take time to look for it. This requires more time and it’s a patient search, involving the client in the dialogue and creative process.”

Beyond in-depth conversations that encourage client creativity, questions such as how the structure will be used, its greater purpose, its narrative function, its educational role, how others will participate in the structure and what happens to it once the owner is gone, are all factors the firm ruminates over to discover a building’s potential, Blonkvist explains.

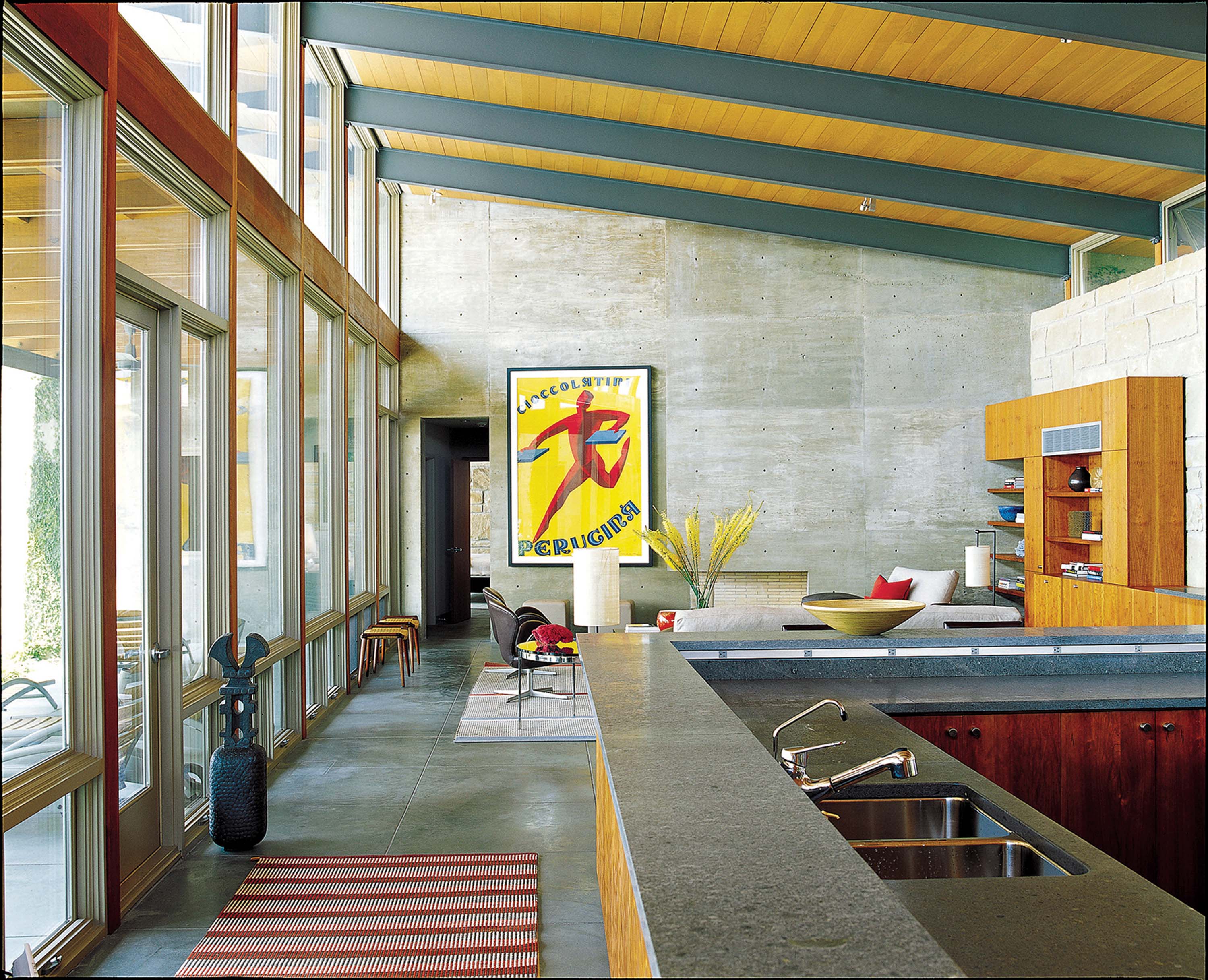

These concepts and the marriage of art and architecture is experienced, quite literally, in the Dallas Residence for Art, which the firm completed in 2012.

The home’s design highlights an extensive contemporary art collection through a series of layered planes and volumes. The 11,109-square-foot home — constructed of limestone, zinc and glass windows walls — was designed to exhibit 60 years of Post-war art, including works by Ellsworth Kelly, Martin Kippenberger, Richard Reimer, John Chamberlain and Andy Warhol, among many others. But it is also a family home that needed to be warm and comfortable.

“The design of the house grows out of an understanding of this art in this period of time, so it would be not just a backbone or blank canvas, but something appropriate for the art,” Blonkvist says. In dedication to the concept, Overland placed every work of art from the homeowner’s collection in the 3-D model of the home during the planning phase. Walls and rooms were adjusted to accommodate certain works and thought was given to how to facilitate the placement of new works the couple might acquire.

The home is at once a livable and relaxing space that maintains a museumlike feel, with open spaces, meticulous lighting design and an unencumbered flow. The home also needed to harbor large groups of people as the couple opens their home to the public for viewings and invites major institutions to host art programs onsite. In addition, a 1,000-square-foot guest curator’s suite was added during construction.

Careful consideration of the site led to a structure that is nestled among the trees and straddles a natural creek.

Water rushes below the master bedroom, providing a serene acoustic. “We try to find a way to meet the programmatic needs, but also listen to the landscape. We could have kept the whole house on one side of [the] creek and left unused land across [the] creek and packed more in, cut more trees. But instead we explored the idea of crossing the creek,” says Blonkvist, noting that not a single tree was removed during construction. “That’s engaging the site in a different way. It’s really incorporating the natural assets of the site into the design and it also allowed us to protect and preserve the landscape that was there.”

The thoughtful and collaborative approach to architecture ensures that Overland Partners will continue to build structures that tell artful narratives in their placement, intention and design.

- The retreat’s design was inspired by the historic culture of stone and adobe building materials found in the southwest. Rainwater and greywater harvesting systems are used to irrigate roof top gardens. abundant use of natural light and the building’s orientation capture views and natural breezes to reduce the need for mechanical and electrical systems.

- Overland Partners’ headquarters, in san antonio, texas, is a renovated Hughes Plumbing warehouse built in 1918. the building is organized around am exterior courtyard. these three steel gates, designed after a Jackson Pollack painting, were once loading docks.

- Located just minutes from the historic Santa Fe plaza in New Mexico, this 24,000-square-foot private retreat and residence served as a prototype for a sustainable compound, earning LEED Platinum standing.

- Exterior materials of stone and concrete are brought into the house to further emphasize the blending of indoor and out-door spaces.

- Overland worked with L’Observatoire International, a lighting designer and consultant that’s worked with major institutions, including the Guggenheim Museum, for the home’s lighting design. Hidden beneath coves, there are two or three types of light bulbs that change at dusk so an even distribution of light washes down on the walls and the art can be viewed at any time of day with clarity.

- Lakeside Residence; Horseshoe Bay, Texas

- The Dallas Residence for Art is a family home designed to highlight a major contemporary art. Art works were placed in the house depending on their size, association with one another and sensitivity to natural light.

- The 1.5 acre site of the Dallas Residence for Art straddles a tributary of a creek. Consideration of the site lead to a home organized in a series of transparent and solid planes oriented to the creek and natural surroundings.

.jpg)

.jpg)

No Comments