05 May Rendering: Designed for the Desert

Ask Michele Shelor and Allison Colwell to explain their Phoenix, Arizona-based landscape architecture firm’s philosophy, and they immediately jump to the practical — sustainability.

“It’s part of every project,” Shelor says. “Another is really strong bones, the hardscape. We’ve been told we’re the architects of landscape architecture. What is meant by that is we have simple, modern, and timeless hardscape, and the garden around that provides the romantic, the poetic delight.”

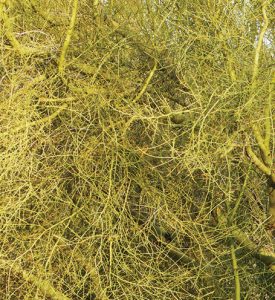

The client wanted something completely unique, asking for “strange” cacti and succulents. The plant palette includes octopus and monstrose apple cacti and a rare Boojum tree. Photo: Marion Brenner

The two opened Colwell Shelor Landscape Architecture in 2009, at the very bottom of the recession. That optimism has since been recognized with dozens of awards for both residential and public projects that reflect their profound love and respect for the desert.

Neither came directly to landscape architecture. Shelor graduated from Arizona State University (ASU) with degrees in history and political science with an emphasis on Latin American studies. She figured the next step should probably be either law school or teaching, and she went for the latter. She lasted three weeks. On a whim, she took a gardening design class at the local community college, where her obvious talent was recognized, and she was encouraged to pursue it seriously. So it was back to ASU for a degree in landscape architecture.

The collaborative effort with the client transformed the garden into a landscape that has inspired appreciation for the desert and conservation. Photo: Caitlin Atkinson

Colwell, on the other hand, was inspired by a drafting class during an elective course in construction management at Colorado State University. She went on to graduate from the University of Oregon’s School of Architecture and Environment and worked for architecture firms until relocating to Phoenix and having children. But architecture was too time-consuming for the mother of small children, so she answered a help-wanted ad in the newspaper for a part-time job at a landscape architecture firm. “That’s how I ended up working for Steve Martino,” Colwell says, “and Michele and I met there.” Martino is an acclaimed landscape architect, and the women agree they couldn’t have had a better starting ground.

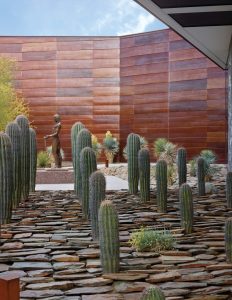

Around the entry courtyard, sculptural arrangements of cacti form a gallery. Photo: Marion Brenner

Once Colwell’s children were school-age, Martino urged her to take up landscape architecture as a profession. “At first, it was like, ‘Oh no, no, no,’” she says. “And then he had such amazing projects, and over time it just felt like a better fit for my soul.”

Shelor and Colwell agreed that once they had their licenses, they’d start their own firm, which happened to coincide with a recession. Their first project was a wedge-shaped pocket garden fronting a Scottsdale office building. The architect wanted a way for the building to interact with the public, and Colwell and Shelor designed a bench, a triangle of golden barrel cacti, and a raised concrete planter of horsetail reeds bordering a small water feature.

From the pool house, the view ovelooks Camelback Mountain. Wildflowers splash the area with color. Photo: Caitlin Atkinson

“It was a postage stamp of a project,” Shelor says.

“I think we got paid in beer,” Colwell laughs.

It also won them their first award.

“We look at the exterior spaces very differently than an architect does,” says Colwell. “And it’s important. It’s our specialty.”

From the pool house, the view ovelooks Camelback Mountain. Wildflowers splash the area with color. Photo: Caitlin Atkinson

The firm’s relationship with light, water, and color sets them apart. “We don’t use color in our hardscapes. Not at all,” says Colwell. “We try to keep the hardscape very clean, modern, and minimal, and the color comes from the plant material. We try to choose plants that have seasonal color, so you’re always getting some kind of bloom. But in lieu of color, we also employ texture and shadows. And we often use rock in playful ways.”

“I think one thing that’s very difficult about living in the desert is that we can’t always use all the great new sustainable materials because they disintegrate in the heat,” Shelor says. “We use concrete, and we know that’s not sustainable, so we’re always looking to reduce the amount we use in our hardscapes. But it’s one of the few materials that can hold up in the desert. Wood? Forget it! A wood bench doesn’t last more than a year. We do have wood in some projects, but they’re big huge chunks. We use stone, a lot of stone and gravel and so forth.”

In a project titled the House of Desert Gardens, gardens divided into galleries provide a year-round show of cacti and blooming desert flowers.

Colwell Shelor hardscapes echo the pale, sun-bleached shades of the desert floor, which reflect rather than absorb heat and light. They treat the harsh desert sun with all the respect it demands, orchestrating shadows into changing patterns that are both soothing and contemplative. In the same vein, they celebrate water.

Aside from their brilliant red color, the tubular blossoms of golden torch plants provide nectar for pollinators.

“In our large public projects, we do big water harvesting moves,” Colwell says. “But that also applies on a smaller basis to residential projects. We’re often educating the client on sustainability. Most people simply want to keep their water bills lower.”

For the landscape surrounding Scottsdale’s Museum of the West, they designed a “weeping wall” that collects rainwater from the roof and the air-conditioning system. Plants, which are organized into outdoor galleries to mirror the ones indoors, purify the water, which is then either absorbed or reused.

The shady gallery between the guest parking and entry to the house is marked by more tender and colorful succulents, which provide a series of blooms that explode in color for months.

They love public projects for their ability to make a city more vibrant and to affect more people. But they are equally absorbed by residential landscaping. “With residences, there’s that level of detailing,” explains Shelor. “You can experiment more on the residential.”

One project with views of Camelback Mountain has a hardscape that echoes the chalky quality of the desert floor the owner observed while cycling, and nowhere is this more striking than in the contrast between the white painted concrete around the black swimming pool. But the design also makes use of rich green elements, including creeping fig vine, native plants, and palo verde trees, along with sculpturally placed cacti.

The entry drive and perimeter line were reconstructed and replanted to reflect the surrounding Sonoran Desert and provide a decompression from city life.

In the case of The House of Desert Gardens, the clients were advocates of Phoenix’s Desert Botanical Garden, but their own home had little to do with the arid landscape they loved. Shelor completely transformed their garden to truly reflect the Sonoran Desert.

In Paradise Valley, Arizona, the firm designed the setting for Ghost Wash by removing a water-intensive 1970s plant palette, 6,000 square feet of turf, and a 20-foot-tall hedge of Oleander. Then they planted cacti, wildflowers, and grasses native to Camelback Mountain to connect the home to its location. “We still go over to Ghost Wash every year and walk the site,” says Shelor. “Because plants are living. They die. A garden constantly evolves.”

Golden barrel cacti tumble below a dozen majestic candelabra cacti.

That’s not the only project Shelor and Colwell monitor. Since their living design elements are in constant flux, they maintain far longer working relationships with clients than many architects. And they’re often exasperated by clueless gardening services that over-prune plants and trees. “They can destroy your trees in a couple of years of over-pruning,” Shelor says. “So we babysit our projects a lot. Having a relationship with the maintenance crew, whether public or private, is crucial, and we say, ‘Okaaaaay, don’t touch! Let it get overgrown!’ And the more we do that, the more people buy into the vision.”

These days the two are far too busy to work on every project together, so they divide most of the work. “We definitely review each other’s work, and every time we do that, it becomes better,” says Colwell. “We value each other’s addition to each project. So we both have our hands on it, but it’s not as intense as it used to be, except maybe with the big projects.”

Each gallery along the pathway has its unique presence and focal point. Here a towering totem cactus provides a contrast with the white wall behind. Photos: Marion Brenner

Of the staff of six, whoever’s free to work on the next project becomes part of a team, but in the end, they all have a chance to engage in every design, getting the kind of education that Colwell and Shelor received with Martino.

At Scottsdale’s Museum of the West, hand-placed slabs of Arizona brown schist provide texture and maintain moisture in a garden of a 65-year-old saguaro cacti, barrel cacti, and yucca.

If they had their way, Colwell and Shelor would collaborate with each architect from the beginning. This tends to happen more often with residential rather than public projects. They thrive on inspiration from architectural design and vice versa. On a nuts and bolts level, they can tell an architect who’s planning a northern courtyard, “Sorry, nothing’s going to grow there.” But on an aesthetic level, they enjoy the fruitful back and forth that elevates the design of both the building and the landscape.

Sandblasted concrete evokes the leather tooling and embroidered apparel of the American West and lead visitors into the museum.

“We always say,” Shelor concludes, “whenever people are reflecting on the best moments of their lives, it’s rare they’re thinking of being in a building. They’re outdoors — they’re in nature, they’re in a garden, in a park, or driving down a tree-lined street.”

The courtyard at Scottsdale’s Museum of the West features a steel “weeping wall,” which is fed by water from the museum’s HVAC system and rainwater from the roof. The 39-foot-long bench was hand-carved from a single beetle-infested ponderosa pine salvaged from Northern Arizona.

Writer and editor Laurel Delp is a frequent contributor to WA&A and other magazines and websites, including Town & Country, Departures, Sunset, and A Rare World.

No Comments