02 Mar Rendering: Form Finds A New Dimension

When Ana and Andy Khawaja bought a plain, mid-century pad in the hills overlooking Sunset Boulevard, their intent was to remodel in the minimalist modern vein they both love. With that established, connecting with Belzberg Architects Group was simply a matter of time. With their reputation for tucking expansive, glass-wrapped structures into gnarly Southern California slopes, and a collection of heart-stopping minimalist residences to back it up, the Khawajas knew Hagy Belzberg and his gang of skilled architects would give them a house equal to their dreams.

And they did. Just fourteen months after their first meeting, the couple’s four-bedroom residence had taken its place among the firm’s design successes. Sun-washed walls become an afterthought while the harmoniously configured space, natural light and surrounding Los Angeles hills come to the fore. A 50-foot-long steel beam stretches across the back of the house allowing an uninterrupted opening to the terrace from one side of the house to the other, the glass doors disappearing into the walls like magic.

“I love it,” says Ana, who grew up in Lithuania. “It feels light. The ceilings are high, and the water feature in the entryway is just what I wanted.”

Another happy Belzberg client.

On the other side of town, in its own glass-wrapped building a few blocks from the beach, Belzberg’s eager crew ply their imaginations and eyes to the fungible space that lies between what is plainly possible and what might be if given a shot. Widely known and lauded for its commitment to innovation, the firm has been using 3-D digital technology (CNC) to solve riddles of form and material since it became available to the industry in the late 1990s. In fact, in 2009, in large part as an acknowledgment of his contributions in the field, Hagy Belzberg was elevated to the American Institute of Architect’s (AIA) College of Fellows. Indeed, if the group has a design signature (and Hagy Belzberg hopes it does not), it would be its bold, even occasionally wild applications of CNC-generated features in its projects.

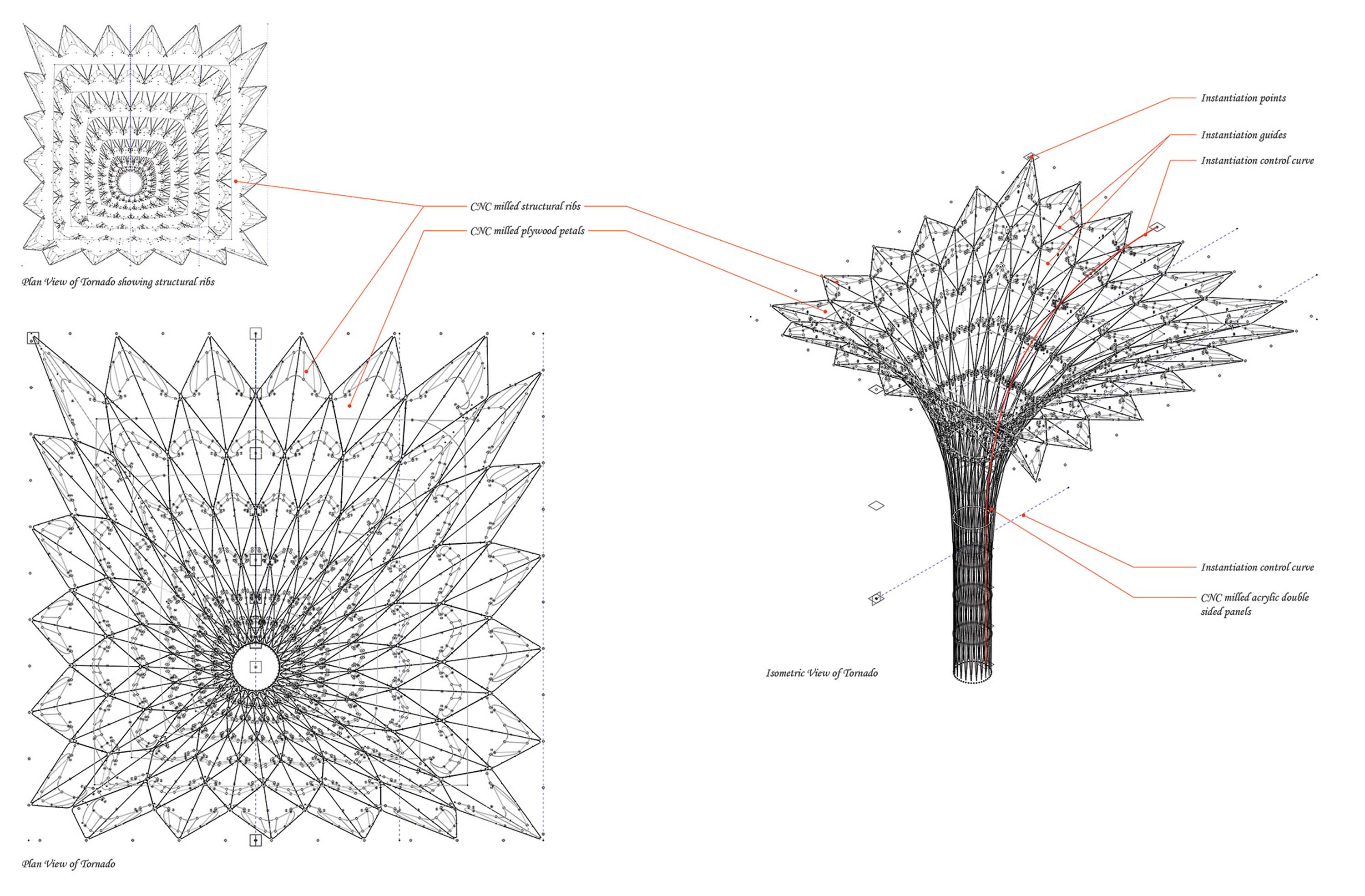

Consider the firm’s 2008 design of the Conga Room at L.A. Live. Faced with the dilemma of a live-music venue located up a flight of stairs in an office building, Belzberg’s award-winning design uses a multitude of triangular-shaped wood panels assembled in shapes like flower petals. The creation rises into a 20-foot-high form, like a tornado, through the dance floor, then expands out to become the club’s ceiling. All of it was configured with CNC digital technology and later fabricated in a local mill shop.

Hagy Belzberg was 27 and newly graduated from a Harvard master’s program when his proposed design for the lobby, bookstore and restaurant of Los Angeles’ Walt Disney Concert Hall — Frank Gehry’s famously curved building — won a national competition. He lined the walls of the ensuing restaurant, Patina, with walnut panels, the soft ripples of which suggest a curtain. Fabricated from a CNC digital file in a mill shop, they lend a sense of elegance without becoming ornate.

The symbolism of the curtain (the stage of the concert hall has none) was Belzberg’s method of drawing patrons into the architecture. The design earned an AIA Merit Award, among many others.

“Early on, we wanted to sort of tell you the meaning [of the symbolism in our designs,” says Brock DeSmit, an architect with Belzberg Group since 2002. “Now [we are] purely about studying these forms and shapes from an experiential standpoint. We don’t want to tell people anymore.”

Since Belzberg’s success at the Walt Disney Concert Hall, institutional, commercial and residential commissions have been steady. Notable among them are the Ahmanson Founders’ Room, The Los Angeles Museum of the Holocaust, which garnered eleven awards including an AIA Honor Award for Architecture, and the Gores Group’s Wilshire Boulevard corporate office building. That building’s exterior features a series of four varying slumped glass panels arrayed in a tiled pattern. Each was configured with CNC software and made by a Los Angeles glass fabricator.

But getting the glass to slump in the right way and in a manner that could be replicated took 18 months of experimentation and mock-ups, says DeSmit. “[In the process of] discovering what’s possible and what’s not possible, and trying to achieve a result, the desired result can sometimes change. I think that’s where the art is in what we do.”

“Before CNC digital, [architecture] was constrained by unit sizes and certain materials,” says Hagy Belzberg. “Digital fabrication allows us to create hyper composition in very dynamic forms, and that’s a hard thing for a human brain to contemplate.”

What’s not difficult for the human brain to contemplate is the peacefulness that a well-designed structure in harmony with its setting exudes, such as the Khawajas’ home in the hills above Sunset Boulevard. A pair of square, two-story apartmentlike wings faces each other from opposite sides of the otherwise single-story dwelling. Like counterweights, each contains a second-floor study — one is Andy’s, the other Ana’s. It is just as they dreamed it would be — minimalist, with easy symmetrical lines and a flow that is wide open and flooded with light.

- Floor-to-ceiling windows and white terrazzo floors allow natural light to flood into voluminous rooms and hallway.

- With its white terrazzo floors, the formal living room is a canvas of beige, ivory and brown hues and a showcase for Los Angeles artist Briggs Solomon.

- The soft curved ridges carved into a walnut ceiling in the residence’s master resemble palm fronds.

- For a house in Kona, Belzberg architects used digital design software to create features that would reflect Hawaiian culture; an entryway pavilion shaped like a woven basket is one example.

- The residence’s exterior is a mix of cut lava rock and teak timber reclaimed from 19th-century barns and railroad ties by the New York company Ter-Mai.

- This 5,800-square-foot residence in the Hollywood Hills takes advantage of 180-degree views of the city. Economic constraints meant only locally manufactured materials were used and grading was kept to a minimum.

- A renovation of a 1960s-era commercial office building for the Gores Group, a private equity firm, gave Belzberg Architects the opportunity to explore different forms that glass and stucco panels can take on a building’s exterior.

- One of L.A.’s premiere venues for Latin music, the design for the Conga room’s new 14,000-square -foot location in 2008 included a tornado-like structure that flows up from the ceiling of the lobby through the club’s dance floor.

- Hagy Belzberg is principal architect at Belzberg Architects Group and AiA Fellow.

- Collaborating with Cuban artists Jorge Prardo and Sergio Arau, Belzberg Architects made diamond-shaped plywood panels, clustered to resemble a series of flower petals, the foundation of the club’s design. serving both aesthetic and utilitarian functions, the panels’ thickness varied according to their need to hide audiovisual, lighting or fire-safety equipment. The design won eight awards including the 2011 AiA Honor Award.

- Eighteen months of trial and error yielded a unique pattern of slumped glass panels. Four different panel forms alternate on the building’s exterior to create an effect that is playful, modern and eye-catching.

No Comments