04 Aug Rendering: The Swaback Synthesis

“On my second day … I was given a bucket of mortar and taken out to a partially completed tent: The softness of the fabric, the earthiness of the stone and the primitive use of fire made everything feel more like The Arabian Nights than anything to do with camping out,” recalls Vern Swaback, FAIA, FAICP, founder of 35-year-old Swaback Partners in Scottsdale, Arizona.

In January, 1957, the 17-year-old had traveled to Taliesin West, in what is now Scottsdale, from his native Chicago. There he had been inspired by Frank Lloyd Wright’s Oak Park homes and Unity Temple — their horizontality responding to the Midwest plains; their sensitive response to climactic extremes and lifestyle needs; the innovative materials used; and their affirmation of a distinctively regional American architecture, divorced from European paradigms.

A year before, Wright had interviewed Swaback at Taliesin, in Spring Green, Wisconsin. The future architect had finished his first year at the University of Illinois but wanted more than academic exercises. He wanted an architectural vision that looked beyond designing structures to one that was viscerally and intuitively created from a spiritual devotion to place, context and community.

So Wright said to Swaback, as he did to all apprentices since he had first chosen the site beneath the McDowell Mountains in 1935: Live in a tent and learn the materials of the desert.

“Living in direct exposure to nature allowed me to practice on myself,” Swaback later wrote in one of his books, The Custom Home. “My tent, ‘home,’ was an encounter with the fundamentals of form, space, light, air, and comfort — the very same variables that are critical in the design of homes from the smallest to the most grand.”

For the final two and a half years of Wright’s distinguished and vicissitudinous life, Swaback served as an apprentice at Taliesin West and practiced at the now National Historic Landmark for another 18 years.

But the master had to be left to move forward: “He either destroys you or you have to kill him in your mind,” Swaback says. “Imitation in architecture is a kind of death.”

In 1978, he founded what is now Swaback Partners, with John E. Sather, AIA, AICP, a graduate of the Frank Lloyd Wright School of Architecture, and Jon C. Bernhard, AIA, NCARB, educated at North Dakota State University and St. Cloud State University in Minnesota.

Today the highly awarded firm, including its interior design division, Studio V, directed by Katherine Pullen, Allied ASID, comprises 28 associates, including two landscape architects and four architects.

“Our varied work rests on three fundamentals,” Swaback explains. “The first is, for any program and budget, design is the greatest variable for creating value. The second is to focus on the relatedness of all things, from the smallest to the largest considerations. And the third is that we engage each client as a co-creator.”

The multidisciplinary firm allocates about a third of its time master-planning communities and cities, with residential and commercial components, including the 5,000-acre Village of Kohler in Wisconsin (1976–92); the 8,300-acre DC Ranch in North Scottsdale (1994–2008; residences to present); and currently, the 1,000-acre Kukui Ula on Kauai, Hawaii, and the 2,177-acre Martis Camp in Truckee, California.

Nonresidential work comprises a second third. This includes the paper-airplane-inspired Hangar One Jet Facility at the Scottsdale Airpark, and the acclaimed Univision headquarters in Phoenix. It also includes the firm’s oasis headquarters, the 14,000-square-foot studio, gateway to the historic Cattle Track arts neighborhood, once home to the world-famous artists Fritz Scholder and Philip Curtis.

In addition, municipal contracts have included the multi-award-winning Chaparral Water Treatment Plant in Scottsdale, built to integrate with the city’s famous Hayden Road greenbelt and community clubhouses, highlighted by the LEED Silver-certified lodge at Martis Camp — celebrating the handcrafted National Park Service lodges and clubs of the 1900s.

Current work includes the 165-room Iron Horse Hotel Arizona on the Salt River Pima-Maricopa Indian Community adjacent to Scottsdale; the Stanford University Golf Performance Center; the Fort Apache Master Plan to show-case the historic structures in the White Mountains of Arizona; and 19 million acres being master-planned for the Navajo Nation in Arizona, Utah and New Mexico.

Each partner, while most often working independently, thrives from many dynamic relationships: “We have enjoyed long-term relationships both with our clients and each other. The Swaback synthesis is a three-part commitment between each of us as individuals, with the future-enriching power of architecture and planning, all made possible by uncommonly varied, able and committed clients,” Swaback says. “We have given our best to the best.”

Luxury homes, especially hillside designs, are the final segment — organic designs in spirit with the place where they will be sited and the community they will join. “The exploratory design of every good house is a microcosm of creating community, including a thoughtful understanding of location, systems, materials and dreams,” Swaback says.

How does a great luxury home begin? “Experience combined with intelligent dreaming is how all great designs come about,” Swaback says. “The process of truly creative designs begins in the spirit with feelings — long before there are ideas, drawings and models.”

John and Mary Margaret Sather’s 2,500-square-foot hillside home in Sedona, an hour and a half north of Scottsdale, was sensitively built into 45-degree angle slopes, and Jon and Teri Bernhard’s 3,950-square-foot home is integrated with its boulder-strewn 1.5-acre lot in Fountain Hills, just east of Scottsdale. “This is a home that celebrates the character and spirit of desert life,” Bernhard says. “Teri and I wanted a home that married itself seamlessly to its environment.”

Similarly configured is Vernon and Cille Swaback’s own home, the 5,000-square-foot “Skyfire,” completed in 1997 in the high desert of Pinnacle Peak, north of Scottsdale. “‘Skyfire’ is my family version of what it felt like as a teenage apprentice, living in close contact to the desert at Taliesin West,” he says. “When architecture is created with respect for the desert, the desert becomes the architecture.”

- A “spa for jets,” Hangar One (2003) in scottsdale comprises 129,000 square feet for up to 15 aircraft in two hangars, office space, a collector-auto gallery and entertainment areas. a 108-foot-long, 15,000-pound aluminum ‘paper’ airplane — a memory from the owner’s boyhood — readies for flight from the roof.

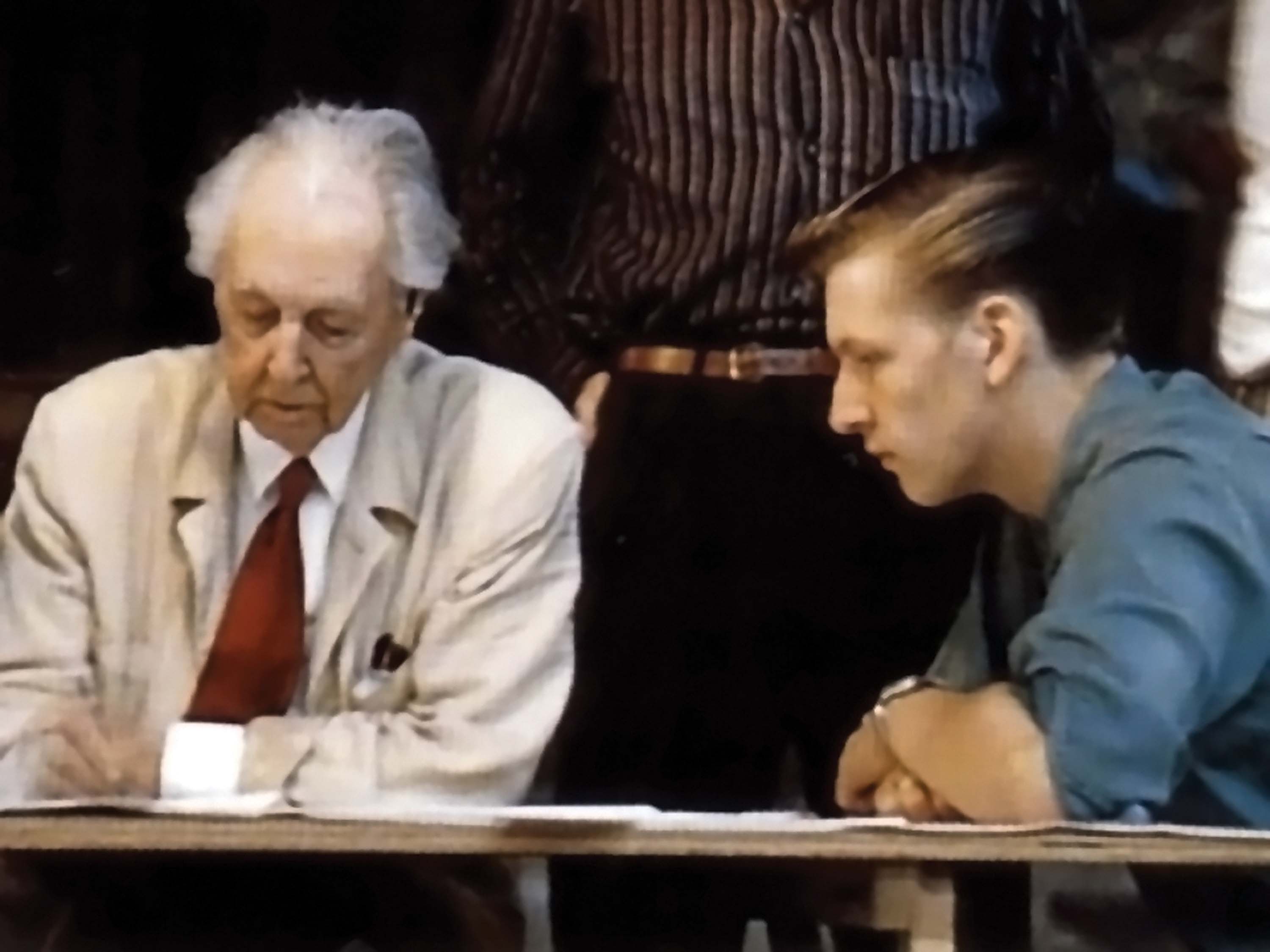

- Frank Lloyd Wright and Vernon Swaback were photographed together, circa 1958/59. Swaback, one of his last apprentices, was preceded at Taliesin West and Taliesin by notables such as John Lautner and Paolo Soleri, who recently died in Paradise Valley, Arizona. “Wright set the stage for all architects,” says Swaback. “[H]is life at such close range … enriches my every thought.”

- The 31,500-square-foot Univision television studio & Corporate Headquarters (2001) in Phoenix includes green principles such as rammed earth, solar sensitive and regionally appropriate materials and vegetation as well as fabric tensile shade structures and a natural water feature meandering and bridging the building and surrounding spaces.

- Designed by Jon Bernhard on 6-plus acres backed to a boulder-strewn desert preserve hill, the 9,000-square-foot Paradise valley Contemporary home (2011) masterfully conjoins art and architecture, offering dramatic approach, extensive water features, the finest materials and mountain and city lights views.

- Zenlike stillness, simplicity, mystery and clarity: the roots of this 8,240-square-foot Paradise Valley Contemporary (2004) are deep in the Far east. Designed by Vernon Swaback, assisted by project manager, Michael Wetzel, the one-level home occupies 1.7 acres, looking south and north, respectively, to landmark Camelback and Mummy mountains.

- This Vernon Swaback-designed home (2011) expresses the beauty of the exposed architectural block, smooth-faced and fluted masonry units, including their seamless use from the outside in. the north Scottsdale site offers views of a desert golf course and the McDowell Mountains.

No Comments