24 Jul Rendering: Windows of Soul

The driving force behind Tom Kundig’s architecture is simplicity.

He frequently recalls his roots to create the poetry of form that has launched him into stardom, not only in the world of architecture, but the international media. Growing up the son of a Swiss architect, architecture called and Kundig went grudgingly. Not because he wasn’t drawn, but rather he hadn’t found a comfortable place to be in its study. Kundig was naturally drawn to science, engineering and the outdoors. But how to meld them with architecture? It was a conundrum.

The conundrum was soon to be dispelled as Kundig began to define who he was as an architect. As a poet will struggle with words and rhythms in an attempt to define his deepest emotions and ideals, so Kundig struggled with how to marry the elements he was so passionate about with landscape and materials into functional structures.

In 2008, Kundig was awarded the National Design Award in Architecture from the Smithsonian’s Cooper Hewitt, National Design Museum. In 2009 his firm, Olson Sundberg Kundig Allen Architects, was named winner of the AIA National Architecture Firm Award. Accolades aside, Kundig’s dedication to the discipline of architecture and his own artful expression are what make him extraordinary in his profession.

Years ago, his watershed project was the Studio House: a combined home and studio of concrete and steel filled with micro-architecture. The kitchen island, stairs and master bathroom are artfully thought out extensions of the aggregate structure. Patinated steel, cast concrete and bronze contrasted with the verdant outdoors while light flooded into the living spaces that, with rearrangement, could be converted into workspace for the photographer/owner. Never without cleverness in his expression of wit, Kundig made the guest powder room in the Studio House frustrating for the user with its shallow sink and too small mirror, but soothed its irritating characteristics with an aura of simplistic elegance and grace. The master bathroom is quite the opposite. It is a successful amalgamation of raw steel and cold, hard concrete into a place of respite and communion with nature. The Studio House proved a valuable exercise for Kundig. His expression of a domicile in industrial materials, garnished with exquisite studies of engineering and delicacies of craft, proved superbly functional all the while wrapped like a precious gift in the lush milieu near the Puget Sound.

The Studio House served as a cornerstone for Kundig, one whose ideas and lessons have been drawn upon countless times as he moved from a place of trepidation into certainty of thought and process. With that conviction came commissions and evolutionary new work, much of it calling on the heavy influence the landscape of eastern Washington and northern Idaho had on him in his formative years. Its wide-open spaces filled with sagebrush, ponderosa forests, lakes and rivers are critical to how he thinks about nature and the response of humans to the different environs of cities and rural areas. His childhood also burned into his mind the beauty of old barns and wilderness cabins. One such structure was Royal McClure’s cabin on Lake Coeur d’Alene, which Kundig recalls vividly. “It was different; it was more about the forest than the cabin.”

Using the subtle lessons of the McClure Cabin, Kundig went to work rendering a commission down to its barest architectural minimum to create maximum exposure to its picturesque surroundings. Direction from the owners was easy: Make it simple. Simple, Chicken Point Cabin is, but not without profound thought and intricate engineering details. In Kundig’s words, “Big window, little house” was his goal.

The concrete-block shell of Chicken Point Cabin sits on the edge of Hayden Lake in northern Idaho. Its relatively small and compact body is accessed through a 19-foot-tall spot-welded metal door scaled to the surrounding pine trees. Approaching the home from land leads the viewer to believe that they are coming up to an intriguing structure in the wilderness, but they are not prepared for the very large detail that sets the dwelling apart from any other. At the front of the cabin is a 20- by 30-foot window. The glass and steel window weighs 6 tons. Through an engineering feat of wheels, gears and counterbalances, a 6-year-old child can open the enormous window to let in fresh air and provide uninterrupted views of the lake. Chicken Point is not just about its extraordinary window, but the joy of simple living. A 4-foot-diameter pipe, reclaimed from an Alyeska Oil Pipeline, makes up the fireplace. The stovepipe intersects the second-story plywood bedroom loft and doubles as a fireman’s ladder to the kids’ sleeping alcove. The kitchen table is a single slab of natural-edge wood supported by a recycled steel-spring coil. As Billie Tsien writes in the book Tom Kundig: Houses, “The work of Tom Kundig takes your hand and says, ‘Stop for a moment and be aware of what you are doing and where you are.’ ”

The words that percolate around Kundig’s work are profound and poignant. His work is a direct reflection of his upbringing. “My mother,” he says, “taught me to be sympathetic to the needs and desires of others.” He attributes his philosophy of life and thus his life’s work to the juxtaposition of his experiences with his parents and many hours with his mentor, sculptor Harold Balazs.

“Balazs sensed there was so much to do in this world and we were lucky to be born into it. With that he brought with him a relentless work ethic,” recalls Kundig. Compared to his reserved European upbringing, Balazs was the Yin to his parents’ Yang. The dichotomy gave Kundig a vibrant and contrasting window to life.

“He grasps life as if it is about to expire!” says Kundig of Balazs. It’s a philosophy Kundig himself embraces. He lives his life with zeal. Artistically, he expresses it with fervor in his unique and thoughtful architecture.

The window of life has been one full of challenges for Kundig, many of which were realized on mountains for which he had a passion to climb. Later he appreciated the substantial degree to which those climbs and experiences impacted his work. Clinging to granite by fingertips gave him a heightened sense of touch and appreciation for tactile experiences. Praying for the light of day to warm his precarious perch on a mountainside shed on him the pure value of light; and when he found himself looking helplessly into blinding snow, Kundig fully realized the power of nature. In life, he learned to think with free form, embracing the West and the freedom it represented, unafraid to strike out and be a pioneer, a maverick.

Freedom of thought and respect for Mother Nature led Kundig to believe that landscape is more important than architecture. “Architecture is an armature for the landscape,” says Kundig. Consequently, the materials that her patina paintbrush works so brilliantly on are those that he favors. Steel in the raw state is fascinating to him; as are aluminum, copper, concrete, brick and wood. He wants them to weather and become as much a part of the landscape as possible. As a student, the buildings he found most influential to his work were those that were rational and useful, and those that were solving issues: lumber mills, mining buildings and working agricultural buildings. Their functional status was made even more fascinating because they were unconsciously beautiful in their attire of basic building materials; materials distinctly hued with endless seasons of snow, rain, sun and wind.

Functional and favorable canvas becomes a mantra of sorts for Kundig and in 2008 he created Rolling Huts in response to a client’s need to add space for visitors. The huts are low-tech and low impact, almost Thoreauesque structures with their primitive looking wheels and pared-down appearance.

They are designed to sit above the ground, providing unobstructed views of the surroundings. In the simplest of terms, they are steel boxes, on a steel and wood platform. Walls are topped by clerestory windows, a wall that rises above an abutting roofed section of the box. Over the clerestory float SIPs (Structural Insulated Panels) in an inverted lopsided V. Guests of the huts enjoy both the 200 square feet of living space and the 240 square feet of deck space that surrounds each one. Inside the quarters are simply created from cork and plywood. The exteriors are no maintenance steel, plywood and car decking.

The Rolling Huts are viable for any season and bring nature up close and personal in any season. They are low impact and meant to be herded into groups where views are spectacular. The huts are a direct response to Kundig’s belief that small spaces are significant spaces: “I think intimate human structures allow for experience of many human issues.”

The Rolling Huts, Kundig’s latest trump in the world of architecture, are the product of varied experience in life and profession. Kundig’s affinity for nature and its impact on his favored materials forms the foundation for his personal style. Add to that his passion for craft, a sincere appreciation for the simplistic elegance of Japanese style and a fascination for engineering, and you have Tom Kundig: an architect unafraid to express his thoughts outwardly, which ultimately become poetic structures.

Thea Marx is fifth-generation born and ranch-raised from Kinnear, Wyoming. Much of her career, including her book and Web site, ContemporaryWesternDesign.com has been dedicated to Western craft and style. Her work also appears in Living Cowboy Ethics, Mountain Living, Western Horseman, American Cowboy and Western Lifestyle Retailer.

- The interiors of the cabin were kept simple, but strong colors were used to balance the strength of the materials that make it so unique. It is a carefree place without pretense, meant to be low maintenance and fun. In every piece of Kundig’s architecture, you see the same thread: a connection to nature.

- In the historic Washington Shoe building on Pioneer Square, Olson Sundberg Kundig Allen makes its home. The skylight, another heavy piece of machinery, is a testament to the firm’s commitment to uniting as many attributes as possible into one element. The skylight provides natural light for the firm, ventilation and it serves as a natural heat stack while giving the staff a form of free art as shadows from the sun play across the white wall just beneath it.

- Big window, little house, is how Tom describes Chicken Point. The 20- by 30-foot window wall is a weighty six tons of steel and glass operated by a hand crank. The wall is slightly canted and through a combination of the drift shaft, gears and fly ball governor, it operates relatively easily.

- The small scale of Kundig’s Rolling Huts in Mazama, Washington, is intentional, the meaning profound. In this beautiful valley you are not meant to stay inside. Inside is a place of refuge at night to sleep and really nothing more. You can stay in one if you like; make a reservation at www.rollinghuts.com.

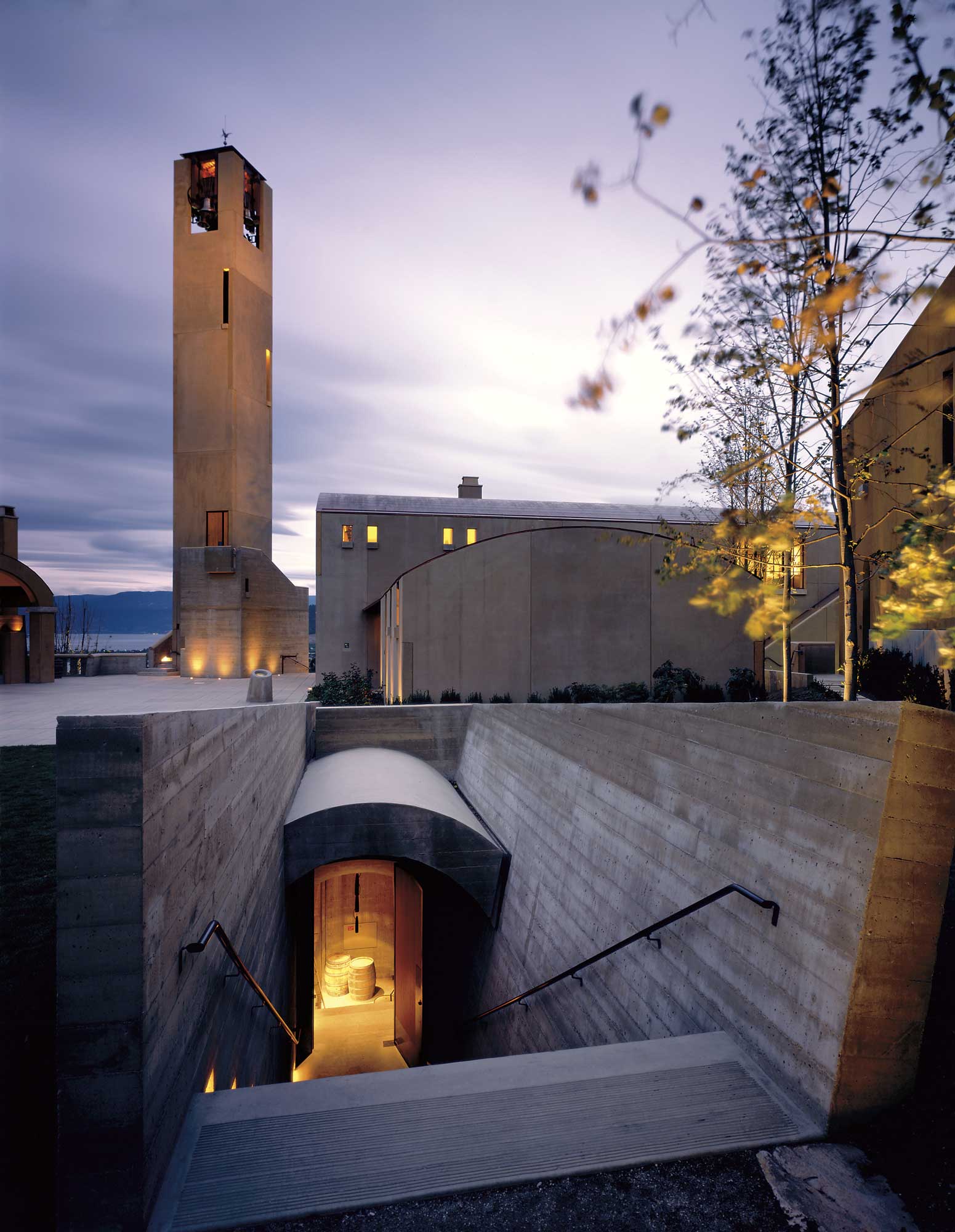

- The Mission Hill Family Estate Winery in West Bank, British Columbia, takes into consideration the basic elements that make wine: sky and earth. Kundig united the two through his award-winning architecture. The cross axis of the cellar is where the architecture from the sky, the tower, meets the earth, the cave. In an artful dance the cycloidic arches make up the supports of the cave that was blasted from the rocks. The 12-story tower is a conduit uniting all the attributes in the wine making process, its bells chiming melodically over a winery that was laid out to create view points back to nature.

No Comments