10 Nov Collector's Notebook: The Art of Place

In the wild backyard of tony Aspen, the majestic twin peaks forming Maroon Bells — fronted by serene Maroon Lake — reign among the most painted and photographed Fourteeners in the entire Colorado Rockies. It is said that interior designers advising high-end clients on respectable décor for their new Great Lodge mansions consider it a cultural faux pas if a portrayal of Maroon Bells is not included in one’s collectible repertoire.

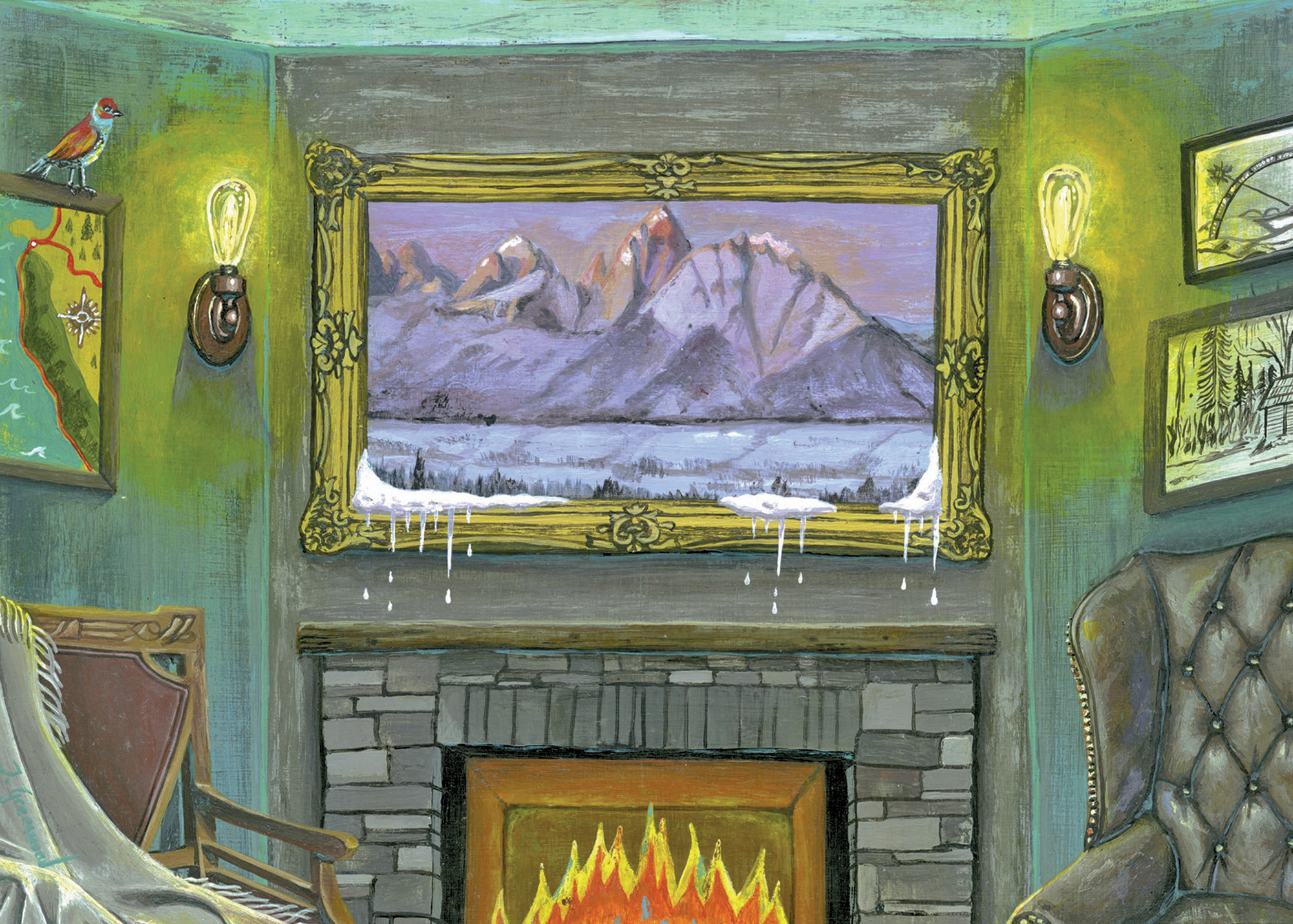

To the north, in Jackson Hole, the most prized pieces of real estate often share one thing in common: picture windows affording priceless views of the Tetons. In the absence of direct sightlines to the actual iconic mountains, the next best thing, of course, is owning a dramatic painting of them.

From historic works by Thomas Moran and Conrad Schwiering to more contemporary interpretations by Jackson Hole locals Jim Wilcox and Kathryn Mapes Turner, place-based art helps cement a sense of geographical connection for permanent residents and seasonal arrivals alike.

It’s the same for those who dwell in Maynard Dixon’s Southwest, Charlie Russell’s High Plains, Russell Chatham’s Paradise Valley, around Carl Rungius’ old haunts of the Wind River Range and Banff, venues intimately plumbed by the artists of Taos and Santa Fe, the late great Tucson 7 and the venerated landscape painters of California.

It’s not difficult to find place-based art; it resides in every local gallery.

The power that emanates from place-based art is something Ann Wolfe has devoted an enormous amount of time contemplating. As senior curator of the Nevada Museum of Art in Reno, she, along with an esteemed, multidisciplinary team of experts, has assembled a truly extraordinary exhibition running through early 2016.

Tahoe: A Visual History is a fascinating examination of the Lake Tahoe region. This unprecedented display of visual objects — and a must-have companion book of the same title — features more than 450 paintings, photographs and artifacts covering a 200-year span.

The trove includes historical paintings by Albert Bierstadt, Maynard Dixon, Thomas Hill, Lorenzo Latimer, Marianne North and Thomas Moran; photography by Ansel Adams, Anne Brigman, Imogen Cunningham, Dorothea Lange, Carleton Watkins and Edward Weston; and the largest-ever assemblage of Native Washoe baskets by noted weavers such as Scees Bryant, Lena Dick and Louisa Keyser.

In addition, there are early maps, survey sketches and journals from the likes of John C. Fremont and John Muir. Topping it off, and no less intriguing, are architectural drawings and photographs that speak to an evolving language associated with the built environment, and design plans from Bernard Maybeck, Julia Morgan, Frank Lloyd Wright and contributions from Maya Lin, Hung Liu and Richard Long.

Tahoe: A Visual History could also be considered a case study for how connoisseurs and younger buyers might approach putting together their own place-based collection.

“Art produced in and about a place helps define its cultural identity,” Wolfe says. “Without knowledge or shared understanding of a region’s art and history, it is impossible to celebrate or critically examine its contributions to the broader culture.”

Dating to the dawn of the Hudson River School, Thomas Cole, Bierstadt, Hill, Moran and other masters cut their teeth cementing the iconography of Niagara Falls, the Catskills and the Hudson River corridor before turning their attention west. Stunningly, in spite of the artist line-up mentioned above, Wolfe says, the Tahoe region historically did not attract a mass convergence of big-name artists the way other places did. Even though, as she points out, a budding newspaper scribe named Mark Twain did gaze upon Lake Tahoe in 1870 and described it as “the fairest picture the whole earth affords.”

Instead, and often at the influence of patrons, Bierstadt, Moran and others were depicting Yosemite Valley, the lower falls tumbling into the Grand Canyon of the Yellowstone, Pikes Peak and Donner Pass, the latter commemorated not only for its beauty but because it became a main thoroughfare for settlers trying to cross the Sierra Nevada.

Bill Rey, co-owner of Claggett/Rey Gallery in Vail, echoes Wolfe in saying that a place-based collection becomes more dynamic when it moves beyond paintings and sculpture, including the significant contributions of native artisans who, after all, have expressed their bond to place for millennia.

There’s no doubt, Rey says, that organizing a collection around place can enhance the experience of owning art. Plenty of evidence exists confirming that place-based pieces rendered by reputable painters and photographers can accrue astounding value over time, though it is, of course, requisite to state there are no guarantees.

Landscapes, human portraits and wildlife scenes closely identified with certain artists and their favored venues have commanded higher purchase prices at auction. And, if one has the time, means and ambition to carry out research, Rey says, assembling collections around place are both profoundly rewarding and educational.

Most contemporary artists are regional with regional markets. That’s where the strength of their reputation resides, Rey says. But occasionally a painter might make a living off of certain landscapes and then throw work into a national auction. “Very few artists from the West fare better at auctions in New York or Boston than they will do in Jackson Hole, Scottsdale or Reno,” he says.

Collectors need to know not only where to buy, but where to sell, too. Collections with a unifying focus tend to possess more marketability than an eclectic smattering of works.

Stuart Johnson of Settlers West Gallery in Tucson and a force in the Coeur d’Alene Art Auction urges caution. Tackling recognized landmarks with a new interpretation sounds intriguing, but what’s the point of redundantly mining locations that are considered clichés, he asks. “So many of these locations have been done a bazillion times. As an artist, wouldn’t you want to present material using a different approach? And, as a collector, I can understand one’s desire to have one of those iconic images, but not 12 of them.”

Many place-based collections are born on the whims of people’s travels and then, when they find a locale where they want to settle, their level of discrimination deepens. The rule of thumb, Rey says, is that it’s better to choose quality when it comes to an artist’s portrayal of place rather than just buying a piece.

“The greatest strategy if you want to revolve around place is to build a collection with focus,” he says. The collection as a whole may take on appeal and more intrinsic value than it would if a collector just randomly buys things as they move through life, he explains.

“It’s not just a matter of getting a piece painted of a place by a well-known artist. If the goal is holding value, then we suggest carefully identifying works of quality that aren’t merely competent, but exceptional works that add weight to a collection.”

Rey mentions Taos artist Joseph Henry Sharp. “He made thousands of Indian paintings, but probably only 10 to 25 percent are high quality and another 25 percent are relatively worthless by comparison,” he says.

Like Wolf, Rey also believes collectors should think broadly. “If a client’s interest is having a Western motif, I’d advise them to think about incorporating vernacular furniture and lighting and books and Native American pottery and objects of antiquity,” he says. “I’d encourage them to explore what’s out there in terms of antique Fred Harvey curio items that were sold to railroad passengers and original furniture by Thomas Molesworth.

Place-based collecting becomes an adventure,” he says.

Collections with a centrifugal place-based emphasis can increase the probability of selling whole rather than being broken up if the collectors or next of kin decide to divest themselves of it. Heartwarming for Rey is that he’s witnessed how the impact of place-based collecting created tighter bonds within families themselves.

They realize that art can move them miles away, in heart, mind and grounding, closer to the pieces of terra firma they love together. It can also convey the spirit of a perceived home even when they live on the other side of the country.

When it comes to having an aesthetic relationship with the world around us, doesn’t everyone pine to have rooms with views of our favorite places, Rey asks. Fortunately we all can have them, whether dwelling in a castle on a hill or in the recesses of a hovel, simply by bringing art into our lives.

No Comments