16 Jul At Home with Billy Schenck

Bill (Billy to his friends) Schenck is one of the leading contemporary Western artists. As a protégé of Andy Warhol during New York’s Pop Art movement in the 1970s, his work is a mix of Photo-realism, Minimalism, and cowboy kitsch that has landed his paintings in the Autry Museum of the American West, Booth Western Art Museum, Denver Art Museum, Smithsonian Institution, Tucson Museum of Art, and too many others to count.

But if you ask him about his greatest creation, he’ll likely point to the compound he created in La Cienega, just outside of Santa Fe, New Mexico.

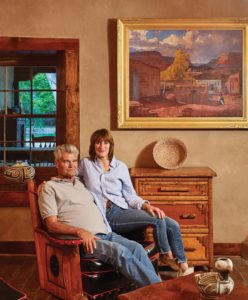

Billy Schenck and Rebecca Carter, his partner and business manager, relax inside their Santa Fe home, which is decorated with a painting of Jemez Pueblo by Carl Redin, circa 1935, and a red-on-buff Hohokam culture bowl, circa 600-750, resting atop a 1935 lodgepole pine dresser made by Bob and Jack Krannenberg of Jackson Hole, Wyoming.

“I’ve built a perfect world,” he says.

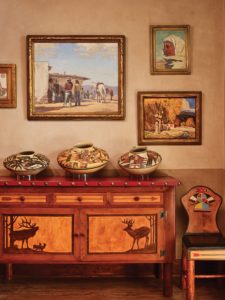

Schenck decorated his home with works by artists he admires. Clockwise from center are paintings by Carl Oscar Borg, Logan Maxwell Hagege, and Ben Turner; prehistoric Indian pottery (Sikyatki Polychrome, 1450-1550); and Thomas Molesworth furniture (a circa 1945 sideboard and circa 1939 chair).

Born in Ohio in 1947, Schenck studied at the Columbus College of Art & Design and Kansas City Art Institute before seeing his career skyrocket in New York in the 1970s — his first solo show, when he was 24, sold out. He then moved west in the mid-1970s, where he split his time between Jackson Hole, Wyoming, and Scottsdale, Arizona. By the mid-1990s, Schenck decided to settle down in Santa Fe. He called Margo Cutler, whose real estate company specialized in historic properties, land, and ranches.

“I gave her just a litany of requirements that I needed,” Schenck recalls. “I just was blabbering like a mad man, and she said, ‘Billy, I saw a property yesterday I think you’d like.”

Recalls Cutler: “It was totally unique, had water and a great location, it was built by an artist, and I thought it was just a wonderful property.”

The place was the home of the late John Brinckerhoff Jackson [1909–1996], Harvard graduate, Landscape magazine founder, author, teacher, and promoter of landscape architecture whom The New York Times called the “Guru of the Landscape.”

Jackson had bought the property in 1947, but did not move there until 1964, when he built a guesthouse at the top of the hill and the main house down below in 1965. “He put in every tree and bush all the way back to the creek, with the exception of one big, old cottonwood,” Schenck says.

But more than 30 years had taken a toll on the property, and when Schenck saw it around early November 1996, he found the house “in a terrible state of disrepair.”

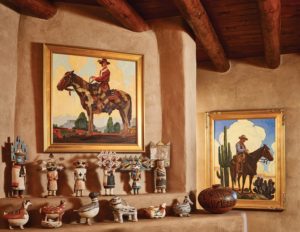

Above the mantel and to the near right are paintings by Logan Maxwell Hagege. The first kachina to the right of the fireplace is by Randy Brokeshoulder, the next kachina is by Brad Brokeshoulder, and the kachina in the corner is by Nick Brokeshoulder (sons and father). The painting over the sideboard is by Dennis Ziemienski. The large painting on the right wall is by Hagege, the drawing and painting next to that are both by Maynard Dixon. The couch, floor lamps, and red bench are by Thomas Molesworth. A Navajo “eye dazzler,” circa 1890, is draped over the back of the bench. The coffee table is designed by Schenck. The pots are almost all Anasazi, circa 1000 to 1300 A.D.

Above the mantel and to the near right are paintings by Logan Maxwell Hagege. The first kachina to the right of the fireplace is by Randy Brokeshoulder, the next kachina is by Brad Brokeshoulder, and the kachina in the corner is by Nick Brokeshoulder (sons and father). The painting over the sideboard is by Dennis Ziemienski. The large painting on the right wall is by Hagege, the drawing and painting next to that are both by Maynard Dixon. The couch, floor lamps, and red bench are by Thomas Molesworth. A Navajo “eye dazzler,” circa 1890, is draped over the back of the bench. The coffee table is designed by Schenck. The pots are almost all Anasazi, circa 1000 to 1300 A.D.

With no heirs, Jackson had left the property to the Santa Fe Community Foundation. When the place was sold, proceeds were to fund scholarships for underprivileged children studying arts and crafts.

“They wanted $520,000, and this was 5 acres, water rights with springs going back to approximately the 1850s, it had a guesthouse which was grandfathered in, because you can’t build a full, other house with a main house anymore in the county. I thought, ‘This is perfect. I always have people coming and going and staying, so I don’t have to worry about them running over me, or privacy. Plus, I could live there while I’m renovating this place.’”

Schenck wrote a letter of intent, asked for right of first refusal, and put his home in Jackson Hole and three properties in Scottsdale on the market. When his places sold, Schenck wrote the check. It wasn’t his last.

In the library, both paintings are by Dennis Ziemienski. The mantel displays Hopi kachinas, circa 1900-1940, and Anasazi effigy pots (antelope, mallard duck, bulldog, parrot, dog), circa 1000-1325.

He spent the next 18 months restoring the main house, adding a barn, and building a painting studio and a business studio.

“I kept selling everything else I had to pay for everything. Altogether, we spent another $625,000 making improvements.”

Jackson had added New England charm to a Southwestern-style home with 24-inch adobe walls and 10-feet-high ceilings. “Each room has one door leading to an outside courtyard, and there are formal wood treatments,” Schenck says. “There were wooden floors, and the floors were layered. But at the same time it looked like a rich, out-of-control hippie had built this place.”

Every room was a different color, so Schenck hired help to start stripping wood, sanding floors, sandblasting ceilings, and building an additional bedroom above the Jackson-engineered acequia (an irrigation ditch, common across the Southwest).

Rebecca Carter’s office includes Kayenta Anasazi pots, circa 950-1285, on the Schenck-designed file cabinet; and a Thomas Molesworth desk, chair, and lamp. Schenck also created the chandelier.

Today, the 4,200-square-foot house with two bedrooms, two-and-a-half baths, and five fireplaces is decorated in a blend of Southwestern and log cabin styles.

Navajo rugs decorate most of the floors. Prehistoric Native American pottery, which Schenck has been collecting for years, lines the tops of many shelves, desks, and dressers, and Thomas Molesworth antique furniture — another Schenck passion since his Wyoming days — can be found in every room. Paintings are those of contemporary and historic artists he admires: Logan Maxwell Hagege, John Moyers, Roseta Santiago, Dennis Ziemienski.

Schenck added to the property, designing and building a home on an adjoining lot for his mother, who died in 2014. His main compound includes a 1,500-square-foot guesthouse; a 1,100-square-foot painting studio; and a 1,200-square-foot studio where his partner, Rebecca Carter, handles the business end of Schenck Southwest.

That “perfect world” totals 12 acres, with cattle so that Schenck can practice his ranch sorting (he has a world championship in that sport). “I wanted to live and be Junior Bonner,” he says, referring to the 1972 Sam Peckinpah rodeo movie starring Steve McQueen.

And paint.

“My day starts usually around 6,” Schenck says. “I read the newspaper, so I can throw up and keep my weight down, and go to work around 6:30, quarter to 7, and I paint till about 3 or 3:30. Rebecca helps me full time, I’ve got part-time help, and a studio assistant. We just keep fine-tuning the collections and keeping up the maintenance.”

How often does he leave?

“Not often,” he concedes. “There’s no need to. We’ve fine-tuned it to such a degree, it’s Shangri-La. I know that’s a cliché, but it’s true.”

And like the house’s original owner, Schenck plans to leave his Shangri-La to Carter and a niece to run it as a by-appointment museum.

Schenck designed the dining room table around 1999. He topped it with Tonto and Gila polychrome pottery, circa 1300-1450. The chairs are by Thomas Molesworth, circa 1938, and the back bar, made by Bob Krannenberg in 1940-1941, came from the Cowboy Bar in Jackson, Wyoming.

Schenck designed the dining room table around 1999. He topped it with Tonto and Gila polychrome pottery, circa 1300-1450. The chairs are by Thomas Molesworth, circa 1938, and the back bar, made by Bob Krannenberg in 1940-1941, came from the Cowboy Bar in Jackson, Wyoming.

“I had the chance to visit the place about a year ago,” Cutler says, “and I was really happy to see all Billy had done. He just did an incredible job.”

Says Schenck: “I’d say, ‘Mission accomplished.’”

No Comments