16 Jul Josh Tobey: A Sculptor’s Fingerprint

JOSH TOBEY’S HOME AND STUDIO are situated at the edge of Estes and Rocky Mountain national parks, tucked in amid pine and scrub oak on the rolling, arid foothills of Colorado. Wild turkeys wander into his studio when the doors are open. Hummingbirds dart like pixies, joyously sipping from feeders hanging from the eaves. Elk wander through the landscape, as does the occasional bear. When not sculpting or on the road keeping up with his grueling exhibition schedule, Josh takes on the essential chore of fire mitigation, thinning pines and clearing debris. All in all, it’s an idyllic life, one that has come after years of hard work in pursuit of his art, his voice, and his own vision.

After years of studying and experimenting, Josh Tobey designed his ideal patina composition. He is involved in the patina application on every sculpture. His wall-hanging works are textural and involve compositions and subjects different from his normal body of work. Those patinas are experimental and one of a kind, the artist says.

“Love is in the Air” | Bronze | 19.5 x 16 x 9.5 inches

In the art world, voice is everything. You either have your own voice, or you are imitating your teacher’s, or worse, following the latest trends. Artists can work their whole lives in search of voice, in search of who they are and how to tell their own story.

In Josh’s case, his first and arguably most influential teacher was his father, Gene Tobey, who, when Josh was 5, quit the security of teaching ceramics at Linn-Benton Community College in Oregon and moved to Santa Fe, New Mexico, to pursue a career in fine art.

Recalling those early days, watching his dad struggle, Josh says, “I remember hearing him say that maybe he’d have to sell Rainbow vacuum cleaners. To this day, I have more respect for artists who have had to struggle.”

His father’s determination and sense of humor have undoubtedly played into Josh’s own outlook. Indeed, listening to Josh recount his childhood spent traveling to his father’s art exhibitions across the country, riding horseback to the Shidoni Foundry to check his bronze work, hanging out in the studio helping polish and finish sculptures, it’s as if the road had been laid out before him from birth. Yet, always there was something imperative propelling him: a fierce desire to create work that was of himself.

To this day, Josh holds dear his father’s words of wisdom. Like the time his dad, noticing how diligently Josh had worked with the foundry artists developing new patinas, said, “Man, I love that you work on those patinas because they look really good on my sculpture.” In other words, “Son, you’re giving away your talent.”

That comment inspired Josh to take the highly artistic job of patination into his own studio, where he now personally patinas all his work, protecting and controlling his formulations.

“Airborne” | Bronze Relief | 14.5 x 26.5 inches

“Airborne” | Bronze Relief | 14.5 x 26.5 inches

“Josh takes the technology of patination and continues to grow it,” says gallerist Greg Fulton of Astoria Fine Art in Jackson Hole, Wyoming. “I’m sure, if Gene were here, he’d say his son had completed the process.”

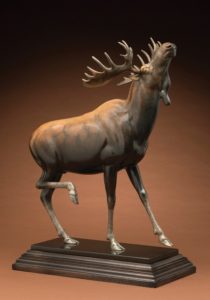

“Mystery” | Bronze | 66 x 43 x 53 inches

“Legend” | Bronze | 69 x 76.5 x 53 inches

Unique patinas, however, don’t tell the entire story. For Josh, the moment that finally signified a break from his father’s influence came in the form of a trio of bears, The Conspirators, in 2006. “When I was in college and guiding fly-fishing groups,” Josh recalls, “I encountered three bears getting ready to raid a campground. I’ve got a big sense of humor and they reminded me of my friends having a bad idea over a few beers. It was an image that I carried for years without a clear concept. … It was one of the first pieces [in which] I implemented something that is innate to me: an anthropomorphic spirit.”

That sculpture did something else: It blended the best of Gene’s technical teaching — smooth surfaces, simplified shapes, clean, clear concept — with Josh’s personal vision. The Conspirators was a breakthrough and helped cement Josh as a force on the wildlife art scene. With each new sculpture, Josh continues to stress the ideas of solid compositional form while allowing some part of himself to subconsciously wend its way into the finished work.

“Discovery” | Bronze | 65.5 x 41 x 59 inches

“Autumn Ballad” | Bronze | 43 x 25 x 18 inches

“I’m not always sure how I do that,” he says, adding, “I think that’s my own artistic fingerprint.”

Over the last two decades, Josh’s oeuvre has expanded, always staying with the smooth surfaces that take countless hours to achieve but taking on a wider range of subjects. And he’s tackled larger-scale works — he took the original trio of The Conspirators, for example, and made them life-sized. He is also finishing up a life-sized herd of bighorn sheep. “I spend a lot more time studying the subject and knowing the anatomy,” he says of his recent work. “I’m more into my subjects and want to get the details correct. I used to worry about what I would sculpt next. Now, I’m so out in front of what I want to sculpt, I have enough ideas.”

Near the end of his life, Josh’s father asked his son if he was ever angry with him for getting him into this life. Josh’s answer was an emphatic: No.

“Jackson Symphony” | Bronze | 30 x 21 x 20 inches

“Jackson Symphony” | Bronze | 30 x 21 x 20 inches

“The Joy of Life” | Bronze | 56 x 13 x 8 inches

“One Too Many” | Bronze | 2.25 x 18 x 4 inches

No Comments