11 Jul Artist Spotlight: Allison Leigh Smith

Through her work with animal rescues and sanctuaries, cleaning cages and transporting injured wild animals to urgent care, Allison Leigh Smith translates her intimate knowledge about each animal into a personal portrait. Her paintings contain more than just the animal. They reference subjective experiences with subtle imagery, textures, scratches, or scribbles, speaking not only to the perilous condition of the animal, but to our humanity.

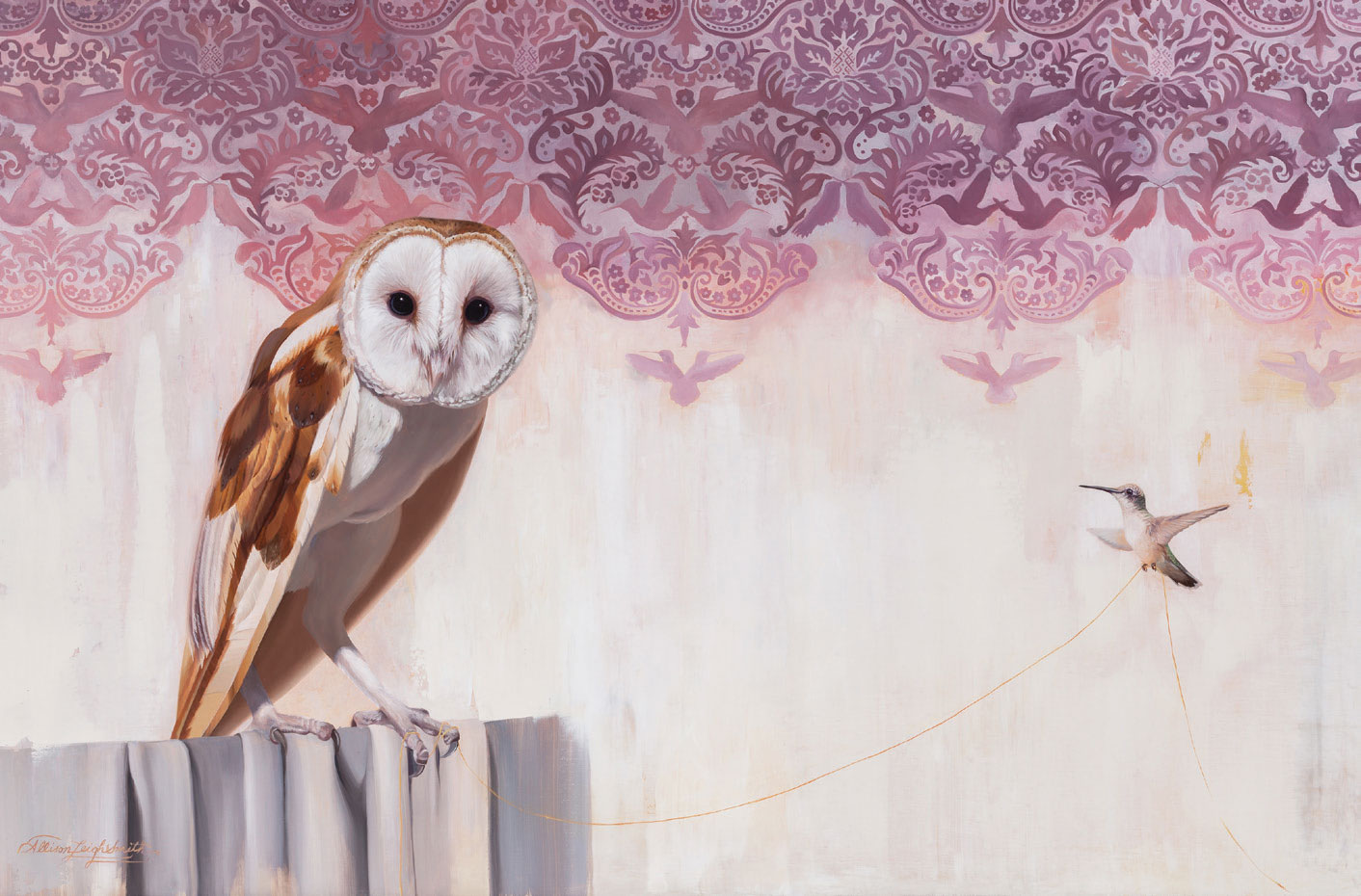

Rise | Oil on Canvas | 18×38 inches

“The rehab work I do is humble,” she says. “It includes emergency pick-ups. I’ve done raptor pick-ups, and that is scary. I feel like it makes my work more authentic. I try to incorporate the awe and emotion that goes into the injured wildlife and the people who save them. That’s how the paintings developed.”

Many sanctuaries keep the animals that can’t be released, and those are the ones she paints the most. She brings her camera into the facilities and concentrates on getting to know each one.

“The personalities come through in the eyes,” she says. “There’s always a connection, a direct conversation between the animal and the viewer, so you feel like you’re looking into their eyes. I want people to experience the love I feel for the animal. That’s why I eliminate the foliage or background, so it’s just about the animal.” Behind the portrait, Smith adds abstracted elements that may reference her personal experiences. “It describes what I felt when I was with them,” she says.

The Samurai | Oil on Canvas | 24 x 38 inches

For instance, when she was in Mexico photographing a heron for her work, she included her dog (who came with her), some feathers, a stingray she saw while there, as well as other wildlife. While looking at the textured background of the finished work titled The Samurai, these images are integrated into a damask-like wallpaper. Another painting of a deer is a personal story. “We had a horrific wildfire, and I was worried about the wildlife,” Smith says. “The deer is about the circle of life and death; there are flowers and bones, and the color of the background suggests a fiery red.”

The writing that appears in some of her pieces comes from her grandfather, a pianist who fortified his income with calligraphy. “Street art and graffiti are a kind of modern-day handwriting,” Smith says. “If I include handwriting, it’s very gestural and imperfect, but it speaks to my ancestry and my family.” Recreating her history, a nod to where she came from, and her grandfather is how she keeps the work personal. The more of herself she contributes to a piece, the more authentic it appears. She aims to access a kind of universal history, saying something new about the wildlife that many people love.

She also uses degraded brushstrokes to portray her empathy and deep concern about the animals’ place in the world. “I feel compelled to do this mysterious background; to show an environment that evokes an uncertainty,” she says. “The animal has to look hopeful and healthy, but they’re in an environment that doesn’t echo that, and it speaks to my fear of our role as conservators of the planet.”

Smith’s painting, The Common Thread, was recently added to the permanent collection at the National Museum of Wildlife Art in Jackson Hole, Wyoming, which will show her work September 7 through October 6 during Western Visions. Her work is also in the permanent collection of the Leigh Yawkey Woodson Art Museum. Smith is represented by Astoria Fine Art in Jackson Hole, Wyoming; Horton Fine Art in Beaver Creek, Colorado; and Trove Gallery in Park City, Utah.

No Comments