13 Jul Movement & Emotion

SHE CALLS IT THE “PERFECT ACCIDENT.” As a fine art student focusing on sculpture at Colorado State University (CSU) in 1990, Sandy Graves completely misunderstood her professor’s assignment. He said to create a “hollow form” to demonstrate the lost wax process for producing bronze sculpture. He meant a wax version of something like the hollow Easter bunnies, made by combining two halves of a chocolate shell. Instead, Graves used wax to carve a horse whose stylized body contained negative spaces, empty all the way through.

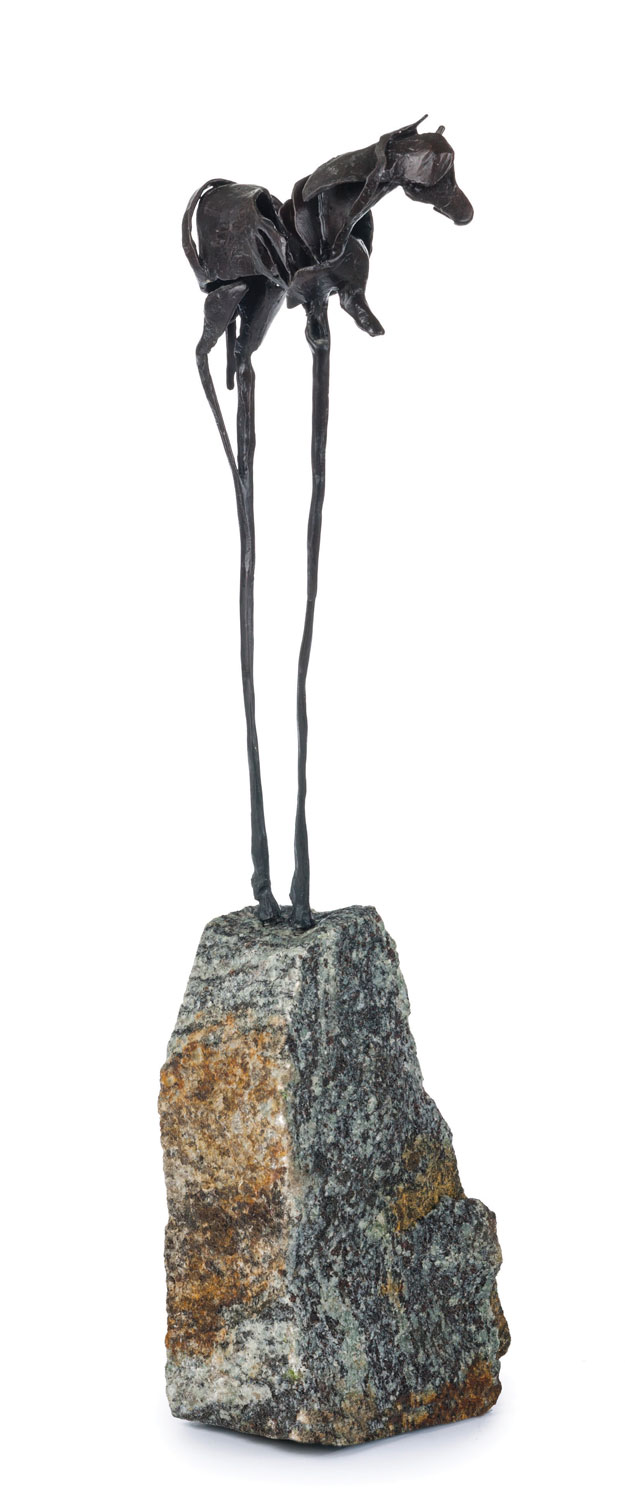

El Caballo de Salvador | Bronze | 15.5 x 7.5 x 3 inches | 199

The piece, El Caballo de Salvador, turned out to be the precursor to the award-winning sculptor’s widely collected animal and human figures. Although, at the time, her professor told her it could not be cast as an edition because it could not be made into a mold. The artist later discovered that wasn’t true. It could be reproduced; it’s just a complicated, labor-intensive process that requires advanced mold-making and foundry skills.

Graves was motivated to find out if her college “mistake” could be produced as an edition after its 2005 exhibition at the Steamboat Springs Art Museum in Colorado. Even though El Caballo was clearly marked “not for sale” — it had been on the artist’s coffee table for years — three potential buyers wanted it. The Chicago-based collector who eventually purchased it encouraged Graves to create more in that style, and bought many of those as well. Up to that point, Graves’ art had focused on realistic figurative bronzes, including a number of public commissions. With the new style, her career took off beyond what she ever dreamed.

Graves’ early career dreams were not of fine art at all. Believing she needed to be practical, she was thinking of sewing or fashion design. A shy child raised on a small farm outside Scottsbluff, Nebraska, Graves designed and created her first stuffed animal from a bed sheet at age 8. Throughout high school, she spent summers sewing in the basement of the family home, winning 4-H awards and regional and national sewing contests. Her father, an orthopedic surgeon, modeled an insatiable need to create, building and making things whenever he wasn’t at work. From her mother, a homemaker who later worked as a psychiatric nurse, the future artist inherited a perfectionist bent.

Graves was not exposed to much original art growing up, but one visit to the Denver Art Museum as a pre-teen made an indelible impression. Of all the works before her, she found herself mesmerized by a marble reclining nude. “I was amazed and in love, and I didn’t want to leave her,” she says. “I couldn’t touch her but was just looking at every little movement of that marble and was overwhelmed by the beauty I felt.”

Carrots | Bronze | 32 x 28 x 7 inches | 2015

Team | Bronze | 23 x 14 x 7 inches | 2007

Still, when it came time for college, Graves headed for the University of North Texas in Denton, intending to translate her sewing skills into a career. What she found instead was that although her high school art education had been negligible, she was already better at drawing and design than most of her fellow students. She remembers the revelation: “Oh! I’m not just a seamstress. I’m an artist.”

She transferred to CSU in Fort Collins where her older sister was enrolled. Partway through, Graves left school for a year to live and work as a teaching assistant in Chile, where she had spent a summer as an exchange student in high school. After returning to CSU, she added a teaching certificate to her credentials and earned a Bachelor of Fine Arts with a concentration in sculpture.

For the next 16 years, Graves taught art at a college-prep boarding school in Steamboat Springs. As it turned out, the experience was an invaluable time of preparation for her eventual shift into a full-time art career. “When you teach art to 14-year-olds, you’re constantly creating and none of what you make matters — you do an example, and another, and another,” she says. “You sit and brainstorm all day, so the practice of [artistic] decision-making is intense. And as a practicing artist, the more mediums you work with, the more your world opens up.”

Harmony | Bronze | 25 x 29 x 15 inches | 2017

Also during that period, she was hiking and climbing in the Rocky Mountains, training a dog for search and rescue, and volunteering with a search and rescue team. “All that time in the woods fed my creative side and my understanding of the animals I now create. It gave me my subject matter,” she says. That subject matter continues to be expressed realistically in bronze, but also increasingly in forms with negative spaces that add a sense of lightness and delicacy as well as elements of design. Moving between the two styles allows her to tap into both the meditative quality of detail-oriented sculpting and a more spontaneous, intuitive approach. “I need to do both,” she says.

Fire | Bronze | 25 x 14 x 8 inches | 2011

As she has for many years, Graves works closely with the artisans at Lands End Sculpture Center, a small family-owned foundry in Paonia, Colorado. The owner and previous mold-maker, now retired, worked tirelessly to refine the process to accommodate her unusual sculptural forms. Now another mold-maker continues that process, while the artist herself does most of the patina work — lately exploring more brightly colored patinas — and oversees the complex operation that takes a sculpture from wax to bronze editions.

Gesture and design are integral to the overall effect of Graves’ work, notes Tom Boswell, director of Worrell Gallery in Santa Fe. “Sandy masterfully captures the perfect motion of a swimming fish, swallows in flight, or a crane’s graceful landing upon a rock,” he says.

Along with horses and wildlife, Graves sculpts the human figure, often in whimsical or heartwarming ways. With all her stylized work, an unexpected dimension appears when the sculpture is thoughtfully lit. “It’s quite remarkable how Sandy creates an additional, supportive artform in the shadows that are cast on a wall,” Boswell says.

Majesty | Bronze | 32 x 15 x 9 inches | 2018

Especially with her stylized work, Graves sees the specific subject as secondary to the feeling of aliveness, energy, and emotional expression. A bear’s intentionally small head makes the body look larger, while a bird with enormous wings emphasizes the sense of flight. In Team, two draft horses with huge hooves and skinny legs and bodies nuzzle each other, communicating the gentle side of these powerful beasts.

Aria | Bronze | 10 x 8 x 4 inches | 2017

“Sandy is truly an amazing artist in both creativity and soul. The love, passion, and sweet spirit she breathes into every piece remain with it,” says Colby Larsen, owner of Park City Fine Art, Old Towne Gallery, Prospect Gallery, and Pando Fine Art, in Park City, Utah. Much of that spirit emerges from the artist’s worldview as the third generation in her family to follow the Bahá’i faith, which emphasizes the unity and equality of all people and a deep connection with life around the world.

In her art, Graves sees this spiritual quality in the importance of negative space. “When you look at my sculpture, there might be a whole leg missing, but the brain fills it in,” she says. “It’s giving credit to what we can’t see and what science can’t prove. Just because we can’t see it, doesn’t mean it’s not there.”

The sculptor, who long ago shed her shyness, also openly embraces a vibrant emotional connection with animals and people. “I want someone to walk in and feel the love I felt for the critter when I was making a piece,” she says. “Art school says there’s little place for love and joy in cutting-edge art, but for me those things are central.”

No Comments