09 Jul Collector’s Notebook: Art Buying Etiquette 101

Collecting art is a personal statement about one’s life, passions, values, and history. Creating relationships with artists gives collectors the chance to bring deeper meaning to the work they’re interested in and also helps them understand life through art. Conversations with artists are frequently lively, sometimes charged with emotion, and are almost always engaging, enlightening, and compelling. Oftentimes, this is how lifelong friendships begin.

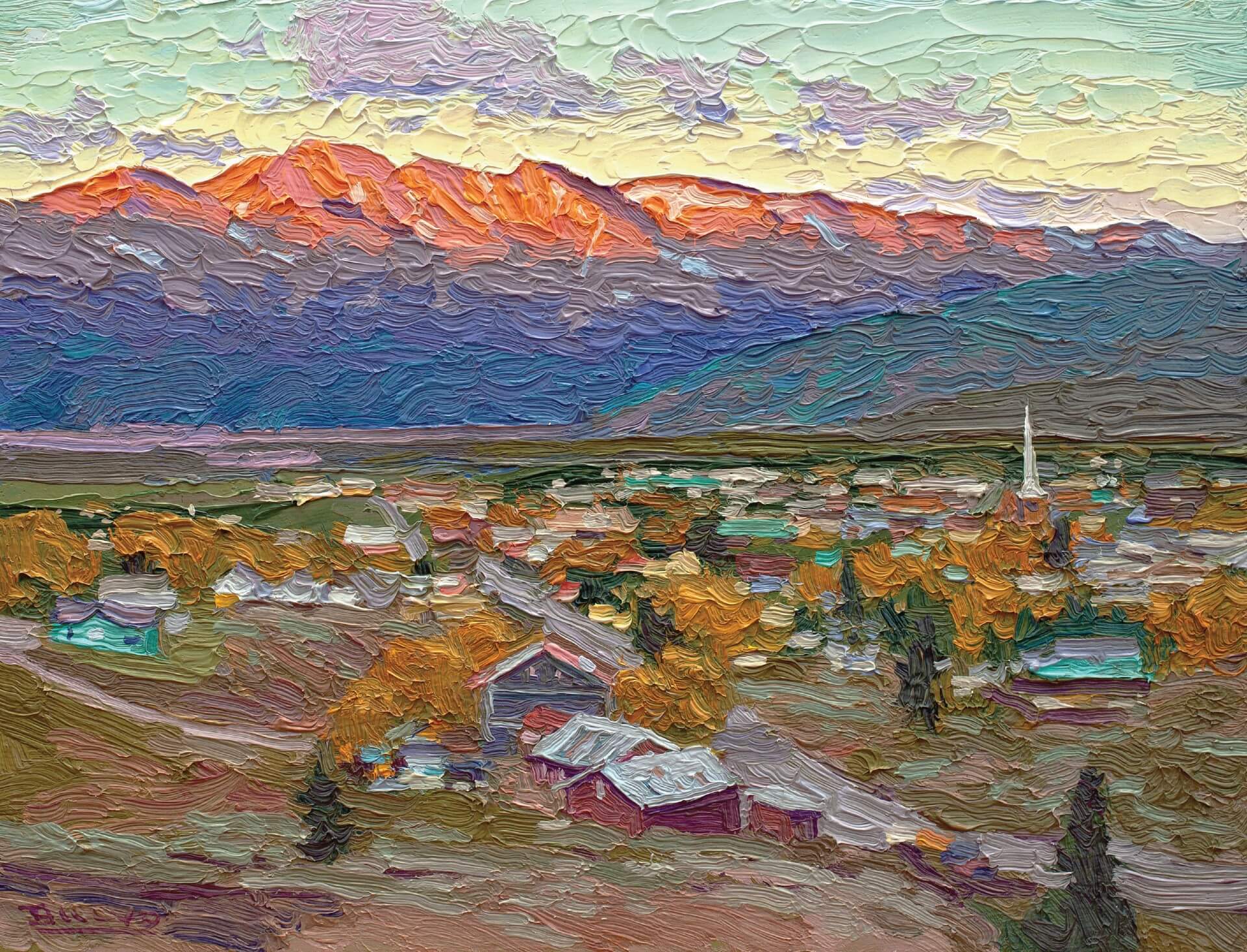

Dan Young, The Last Hurrah | Oil | 10 x 12 inches

And yet, some collectors can be intimidated by artists, possibly for fear of looking uneducated and, thus, inadvertently, saying something insulting. Fear not. Curators, artists, and advisors weigh in on how to make a good first impression.

Kim Lordier, Intricate Dreams | Pastel | 36 x 24 inches

RESPECT BUSINESS RELATIONSHIPS

RULE #1: If you discovered a work of art at a gallery, exhibition, or through an independent dealer, this is where you need to conduct your business.

WHY: When collectors circumvent the dealer where they first saw a work of art — usually to try to get a better deal by cutting out the middleman — what they are really doing is putting the artist’s business at risk. No dealer wants to work with a faithless artist. “Yes, this actually damages the artist’s career; the art community is small,” says Missouri landscape painter Billyo O’Donnell.

Colorado watercolorist Carm Fogt adds, “Think of it this way: When you try to cut the gallery out of their rightful commission, it’s like asking your doctor if you can avoid paying the hospital by going to his house and having him perform surgery there, at a discount.”

ETIQUETTE: Be transparent and work with the gallerist, exhibition organizer, or consultant. And ask lots of questions; it’s their job to educate and guide you through the process. If meeting the artist is important to you, they can help facilitate this.

LAST CALL: BUYING WORK AFTER THE EXHIBIT CLOSES

RULE #2: If you discover a work of art at a show but didn’t buy the piece before it ended, the venue is your first point of contact. For a reasonable period of time after the exhibition closes, say a month, the sale and commission should be remitted to the representing gallery or institution.

WHY: Major exhibitions boost the careers and cache of artists. These exhibitions also expose artists to collectors who otherwise would not have known about them. And then there’s this: “Collectors need to be reminded of the expenses incurred when putting together an exhibition,” O’Donnell suggests, “whether by a non-profit for a cause or a private gallery.”

ETIQUETTE: Contact the show organizers and ask to purchase through them, or, if buying through the artist, ask them to remit their commission to the exhibition. Generally, all artists know to send the commission to the organization where the client saw the work, and some artists remit their commissions up to six months after a show closes. One caveat is if the work has already moved on to another dealer, then the sale goes through that dealer.

DISCOUNTS: WHEN TO ASK OR EXPECT ONE

RULE #3: Discounts are for devoted clients who work with a dealer exclusively or for clients who buy numerous works at one time. The decision to grant a discount is up to the artist and dealer, and many artists simply refuse to allow any discounting.

WHY: In the days before discounted art became ubiquitous, dealers used markdowns as a perk for their best collectors. Commonly, 10 percent was, and still is, the amount given and split between the gallery and the artist, with each side absorbing 5 percent. The problem with discounts, if done frequently, is that they devalue the artist’s work across the board, because everyone who purchased that artist’s work without a discount has, in essence, overpaid. Put another way, the artist’s work isn’t holding its value.

“I remember a collector who commissioned me to do a painting,” recalls Colorado landscape artist Dan Young. “It was back when I was starting out and really needed the money. I did the painting, but then the guy asked for a discount. I wouldn’t do it. I walked away. Twice. Finally, he agreed to the price and bought it, but the whole thing left a bad taste in my mouth.”

“People who truly connect with my work,” Fogt adds, “rarely ask for a discount.”

ETIQUETTE: Ask the dealer or the artist to explain their pricing structure. Ultimately, prices are predicated on the artist’s longevity in the market, consistency of work, awards, honors, publications, stability of prices, invitations to national exhibitions, and inclusion in major private or public collections.

COMMISSIONING ARTWORK

Rule #4: No art directing allowed. The artist is not an extension of you.

WHY: Commissioning an artist does not give you free rein to request anything beyond size, medium, and desired subject matter. When starting the commission process, always keep in mind that the artist doesn’t live in your head and you do not do their work for a living.

“I’ve realized, over the years,” says California landscape painter Kim Lordier, “that trying to get inside someone’s head to understand what they are feeling is very difficult. Now, my process for commissions is to create ideas, then allow for right of first refusal. If I’m presenting the collector with a piece that I am proud of, it will be worthy of one of my galleries.”

ETIQUETTE: Commissioning an artwork can be an extensive process. See page 81 for a list of specific things to keep in mind.

STUDIO VISITS: A TIME-HONORED TRADITION

RULE #5: Never show up unannounced. And do not assume you can buy anything out of the studio or purchase work at “wholesale.”

“I rarely invite collectors to my studio,” says Lordier. “Sometimes it feels like people are rummaging through my lingerie drawer. I feel judged, and I feel compelled to make excuses for why this or that is at a certain stage, even though that is not the visitor’s intent.”

WHY: Studios are sacred spaces. They are personal and creative, but also professional places of business. Once you have an appointment, plan for an amazing behind-the-scenes opportunity by researching the artists before you go; this way you’ll have the background information covered and you can jump right in.

ETIQUETTE: Keep judgments to yourself. Ask questions, especially if an artist uses a term you don’t know. And tell the artists what you like and what interests you about the work. Always keep in mind what a rare honor it is to be invited into a studio.

“Collector’s Notebook” columnist Rose Fredrick writes a regular blog, The Incurable Optimist, where she presents in-depth interviews with artists and covers the art market, collecting, and exhibitions at rosefredrick.com.

Dive Deeper

The dos and don’ts of commissioning artwork

Artistic License: Drop all preconceived concepts and let the artist do what they do best — create.

The Dotted Line: The artist and client should agree on general ideas and subject matter, price, and the timeline for completion. Then put this agreement in writing.

Be Patient: You may ask for updates throughout the process, but that’s it. No surprise studio visits, no emailing color suggestions or photos of your dog that you’d like the artist to slip in.

Nothing Personal: Many artists won’t accept commissions, so don’t assume they’ll jump at the opportunity or take it personally if they refuse. Many artists have a horror story about a client who decided, mid-process, to dictate unreasonable changes. The result: either the client was fired or the work was rushed just to get rid of the client.

Hire Help: Consider using an art dealer, gallerist, or consultant to manage the process; they can work through issues that arise and keep the project on target.

Payment Terms: Expect to pay 50 percent down, knowing you likely won’t get this money back if you don’t accept the finished work.

Points for Originality: Do not ask an artist to replicate a work of art that already exists, especially a piece by a different artist — this is insulting. Original art, whether commissioned or not, is just that: original and unique.

No Comments