06 Jul Along the Pecos

Ben Strickling understands land, not only for the reserves of gas and oil it may hold, which has been his business for decades, but also for what the land can become. He knows how to reclaim and reshape the most rugged terrain; get a silted river to reflow with vigor; build graded roads through wilderness; and plant ponderosa pines whose heights and girths rival those once discovered by pioneers trekking the nearby Santa Fe Trail. In that sense, Strickling is a genuine force of nature.

A trio of taxidermied kudu stares from a wall in the great room of the main residence of the Pecos River Ranch in New Mexico. Owners Ben Strickling and his wife Roxane wanted all the stonework to appear randomly configured.

Strickling, who heads PRI Operating, a Midland, Texas–based natural resources exploration and production company, admits to having spent 20 years looking for the right ranch where he and his wife Roxane might settle and establish as a legacy for their children and grandchildren. In 2011, when Hollywood actor Val Kilmer put his ranch up for sale in Pecos, New Mexico, the Stricklings took a bumpy, dusty ride through the property.

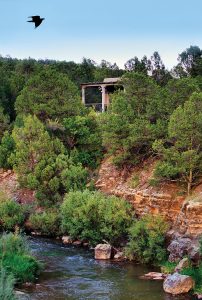

“As soon as we drove in,” Strickling recalls, “I knew this would really and truly be the place for us. I could tell from the land and the nearly 7 miles of [Pecos] River that flowed through it that this would meet all of our expectations for where we wanted it to be.” Although Strickling had spent some years as a boy living in the small New Mexico town of Farmington, he did not know this particular landscape in this part of the state, situated 22 miles east of Santa Fe.

Outdoor terraces focus on the Pecos River, with views of the surrounding canyons and palisades.

While the couple had a clear vision for their 6,000 acres of land and how it should function long into the future, they also recognized what they wanted their new house to be. They commissioned Santa Fe architect Roy Woods to design what Strickling refers to modestly as a “country home.” The resulting 12,500-square-foot main residence, which occupies some 15 acres of tamed and groomed land, presents itself — after a long, circuitous drive that involves crossing a bridge — as a handsome, multi-gabled stone edifice, with an engaging rhythm of recessed archways. At the rear, the house opens up, with terraces as big as stages that overlook the theater of the river and surrounding land.

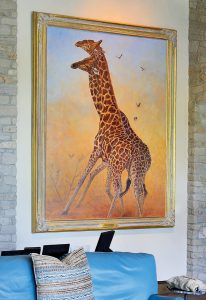

The largest work in the Strickling collection of paintings by John Banovich, Clash of the Titans (9 by 7 feet), depicts fighting giraffes.

Woods, whose Santa Fe architectural firm has been designing ranches and other properties since 1952, looked to houses of the late 19th century for inspiration. “If I had to pick an influence for this house, it would be the Shingle Style residences that people were building in the region once the national park system began to form,” Woods says. The most prevalent material, inside and out, is stone, with multiple varieties employed, some quarried on site. To achieve the resulting forms, the giant stones were tumbled to soften their edges.

But so exacting was Strickling about how he wanted every stone wall to look that he even auditioned stone masons. “We had them do 10- or 15-foot sections,” he recalls, “and if they couldn’t get the right look — one that reflected the way the stones appeared in nature, as if randomly tumbled — then we’d move on to the next mason. We found our person.”

Interior designer Ellen Hinson helped configure and furnish all of the rooms in the home.

Essentially, he and Woods worked to ensure that every stone surface appeared naturally formed — with no perfect horizontals or vertical joints. “Most people want stone walls with straight lines,” says Strickling. “We didn’t. We didn’t want to have a set pattern because nature, geologically, doesn’t have patterns.”

The formal dining room takes in views of the Pecos River.

Ben and Roxane Strickling recently celebrated their 44th wedding anniversary, though “we dated for 10 years before tying the knot.”

Indeed, inside the home’s great room, especially evident on the towering fireplace wall, a light-hued, locally-quarried Oakwood strip stone echoes canyon walls found on the property. “Given that Ben has been in the oil business his whole life, he’s very connected to geology,” Woods says.

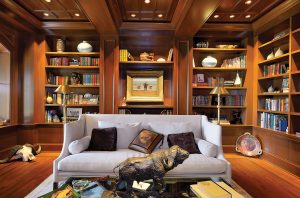

Although the Stricklings brought in interior designer Ellen Hinson (a friend of Ben and Roxane since their high school days in Midland) to help configure their rooms, the couple was confident about the furnishings they wanted and how the house should function as a second residence, apart from their primary home in Midland and an apartment in Dallas. But the most striking decorative elements in the rooms are the many paintings and drawings by John Banovich, a Montana-born artist known for his vivid, honest depictions of wildlife — animals in repose, on the prowl, or in conflict.

“A talented taxidermist is able to create real artworks,” says Strickling of a snarling leopard and its prey, a dik-dik, that hangs in the great room; for many years, Strickling has commissioned taxidermist Karl Brosi, of Midland, Texas, for his trophies.

One such scene, Clash of the Titans, figures prominently in the great room. The 15-by-6-foot painting depicts two giraffes engaged in “necking,” an act far less intimate than that practiced by consenting adults — for in necking, rival giraffes attempt to kill each other by flailing their heads against the opponent’s neck and head. In Banovich’s depiction the fight is so intense that a cloud of orange-gold dust envelops the animals — a detail that imbues the scene with an inherent beauty, but also a brutal honesty about what happens in the wild. “I came across the work in a catalogue for the annual sale of Western art at the Scottsdale Art Auction,” recalls Strickling, who had already become familiar with, and entranced by, Banovich’s art. “I knew immediately that I wanted it,” he says.

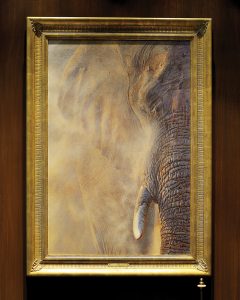

John Banovich’s painting Dust captures the grandeur and drama of elephants, the largest animals walking the Earth.

Elsewhere in the interiors, Banovich canvases and drawings appear like portals to other wild landscapes in the world, including an especially animated one in a guest bedroom showing bobwhite quail in flight. In other rooms, one comes upon herds of African elephants crossing a moonlit river; flamingoes and water buffalo sharing a watering hole; a leopard perched in the knoll of a tree. As a devoted conservationist of land and wildlife, Strickling is particularly admiring of the work of Banovich, whose public 501c3 nonprofit Wildscapes Foundation is devoted to conserving, in the artist’s words, “large abundant landscapes — wild, balanced, and intact ecosystems. There is nothing more important to future generations than wildlife and wild lands.”

“John directly supports the preservation of the African landscape, which I admire,” Strickling says.

A bronze cast of an African crocodile skull (bottom left) occupies a spot on the floor in the library, its shelves filled with books and objects from the Stricklings’ worldwide travels.

Yet, given the menagerie of massive taxidermied bison, kudu, and Cape buffalo heads that stare from the walls of the rooms, one might be confused at first by Strickling’s devotion to the preservation of wildlife around the world. In fact, he points out the paradox of those, like himself, who go on safaris and hunt wildlife, and how that very endeavor ensures the protection of such species. Strickling cites President Theodore Roosevelt, who expanded the country’s national park system, and understood that hunting was a way to preserve wildlife and wild landscapes, in addition to supporting the people who live in such locales.

“With established African safaris,” explains Strickling, “most of the fees associated go directly to conservation efforts, to local communities, for efforts to keep away poachers, help with issues of encroachment from growing populations. Without these, there wouldn’t be any animals. And there are strict regulations in place. You can’t just go and pull a trigger.”

Santa Fe architect Roy Woods fashioned a firepit in the home’s plaza, where chilly winds, even in summer, are tempered by the flames; he also designed and/or remodeled two casitas, a bunkhouse, foreman’s house, two barns, and a house for ranch hands on the property.

As one takes in the vast tracts of Pecos River Ranch, nothing seems deliberate; nature configured the land eons ago. But through Strickling’s ongoing, visionary efforts, he has enhanced nature’s work. His agenda has included rebuilding the Pecos’ banks, establishing groves of silvery aspens, planting fields of native grasses, and digging “drinkers” on the land for animals who might otherwise be reluctant to lap from the gurgling river (whose sounds mask those of predators).

A guest bedroom features a John Banovich painting of bobwhite quail in flight.

Woods worked not only on the architecture but also on the “redesign” of the land. Joseph Urbani, a fisheries biologist and head of the Montana-based Urbani Fisheries, led the efforts to reclaim the miles of Pecos River that course the property. “Joe and his team worked from one end of the river to the other, and when he was all done, you couldn’t tell that anything had been done,” Woods says. “It all looked natural, which is what Ben and Roxane wanted as devoted stewards of the land.”

Once the river-work was complete, Urbani and Strickling restocked the waters with German Browns, Rainbows, Tiger Trout, and other species. “We now have one of the premier catch-and-release rivers in North America,” Strickling says with pride.

Santa Fe architect Roy Woods and Joseph Urbani, a fisheries biologist and head of the Montana-based Urbani Fisheries, worked together to reclaim nearly 7 miles of the Pecos River that runs through the property.

Land on this scale and of such varied topography requires constant attention. “I can tell you that the landscaping is a 365-day-a-year job,” Strickling emphasizes. With much of what he envisioned from the start now complete, both on the land and inside his home, Strickling is more than satisfied. “When you can go to a place and be able to eat meals outside most days of the year and hear the river running by, you know it’s a special place where you live.”

No Comments