04 Jul TRADITIONS IN SILVER AND TURQUOISE

Chipeta Trading Company founder Don Siegel likes to discuss his “three rules of collecting” in the context of the historic Navajo and Pueblo jewelry he sells (or, to use his preferred term, “Indigenous wearable art”). “The first one is to find somebody who’s already made a lot of mistakes so they can share those mistakes with you,” says Siegel, who founded his Santa Fe-based business in 2005 but has been acquiring pieces for more than 40 years. “The second rule is to become a collector, not an accumulator.” However, he emphasizes the final commandment above all: “Read as much as you can possibly read to become a student of the material.”

In an era of flashing screens and mass distractions, some may balk at the idea of accessories that come with a homework assignment. But Siegel, who runs an immersive “Chipeta Experience” out of his appointment-only showroom, believes that educating clients on the heritage of Southwest Native jewelry is the key to selling it responsibly.

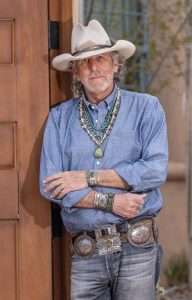

Don Siegel, owner of Chipeta Trading Company in Santa Fe, New Mexico, has been collecting, studying, and selling historic Native American jewelry for more than 40 years.

“In doing so, we teach the people who become the custodians the importance of wearing these pieces and the significance and responsibility that comes with them,” Siegel says.

Unsurprisingly, Siegel has book recommendations at the ready: namely, The Navajo and Pueblo Silversmiths by John Adair and Navajo and Pueblo Jewelry Design: 1870–1945 by Paula A. Baxter. But the veteran collector is also willing to give new aspirants the lay of the land, starting with what he considers the three major categories of Navajo and Pueblo jewelry: the “historic period” running from the 1870s to the early 1940s; the “mid-century period” between the mid-’40s and the 1960s; and finally, the “vintage period” that spans the 1970s up until the dawn of the present millennium. “It’s funny that the most recent period is vintage, but vintage is what comes before museum pieces or antiques,” Siegel explains.

The naja, or double crescent design, has been a symbol of many different cultures dating back thousands

of years; it appears in early Navajo-made jewelry.

The historic period, which Siegel chiefly trades in, begins with the return of the Navajo from their forced displacement to the Bosque Redondo Reservation and the opening of the first trading posts in the 1860s. There, the Navajo began to exchange wool for silver dollars or silver pesos, which were melted down into pure silver rods known as ingots. These were, in turn, made into bracelets or simple beaded necklaces — sometimes with a crescent-shaped naja pendant — by Navajo silversmiths, using chisels, files, and the occasional stamp to engrave patterns.

“Wearing historic Native jewelry honors those ancestors who came before us and their descendants of today,” says Siegel.

By the 1880s, Navajo artisans had begun to visit Zuni Pueblo and train its residents in silversmithing. Knowledge of the craft soon spread to other Pueblo peoples across New Mexico and Arizona, who added their contributions in the form of turquoise stones, notably in the design of tab necklaces and, later, the more intricate squash blossom style.

A selection of pieces from Chipeta Trading Company, including (clockwise from top left) ingot silver and Cerrillos green turquoise cuffs; Navajo silver necklaces dating back to the early

1900s; a group of Navajo and Pueblo museum-quality bracelets; and ingot silver cuffs dating to the late 1800s.

In addition to bracelets, cuffs, necklaces, and rings, another major category for historic jewelry is the concho belt, whose disc-shaped silver decorations were inspired by the Spanish silversmithing the Southwest tribes had previously been exposed to. Concho belts are divided into three “phases” dependent on their period and style, with “first-phase” concho belts (roughly 1875–1900) characterized by diamond-shaped silver plaques with open centers through which a small piece of leather runs.

From the craft’s beginnings, Native artisans hoped to sell their wares to the white tourists who visited trading posts by rail, seeking an authentic souvenir from the Southwest. They succeeded to the point that the Navajo Arts and Crafts Guild (today, the Navajo Arts and Crafts Enterprise) was formed in 1941 to authenticate the jewelry as Navajo-made and ensure quality.

Chipeta Trading Company donates some of its annual profits to Native American scholarships, social justice causes, and non-profit organizations.

The Navajo squash blossom necklace combines elements that are heavily influenced by Spanish designs, including pomegranate flowers, handmade silver beads, and the double crescent

Chipeta specializes in one-of-a-kind historic pieces made circa 1880 through the 1940s

Silver concho belts have always made a strong statement in Southwest fashion and style.

This might also be viewed as the point where Navajo and Pueblo jewelry became a fashionable commodity — and entered its mid-century period characterized by more refined materials, including sterling silver and machine-cut turquoise stabilized with resin. The era also saw a greater variety of stamps being used, including those that left the maker’s name.

“Prior to the mid-century period, rarely did you have Native artisans — whether it was Pueblo or Navajo people — stamping their pieces with their names because there were far fewer silversmiths,” Siegel says of the change. “You knew who was making it, and it wasn’t important to put your name on it.”

These Navajo silver concho belts were created in three phases, all quite distinctive and collectible.

The more commercial quality of mid-century jewelry gained further inroads with the American public, and it was only a matter of time before the wearable art began to appear on celebrities — and on TV.

“I remember growing up and watching ‘Sonny & Cher,’ and Cher’s wearing these big squash blossom necklaces with big jewelry,” Siegel recalls. “That’s the vintage era.”

This epoch saw pieces that had more in common with costume jewelry, as the public craved “bigger and brighter, gaudier and chunkier,” Siegel says. Unfortunately, it also led to a rise of what Siegel dubs “artifakes,” imitation pieces made by non-Natives but sold as authentic Navajo or Pueblo work. Eventually, the situation was addressed by the Indian Arts and Crafts Act of 1990, which introduced steep penalties for misrepresented goods.

“The Chipeta Experience” takes place in Siegel’s gallery in Santa Fe, New Mexico, where he shares the story behind each work of wearable art.

While Siegel notes that there are Native American artisans who continue to carry on the craft at Santa Fe Indian Market and elsewhere, he remains most drawn to the “romance” of the historic-era pieces. It can be a tough category to enter, with prized pieces like first-phase concho belts fetching as much as $30,000. But he maintains that novices can start their collection with historic-era bracelets, which are priced more affordably.

No matter the price tag, just make sure to properly acquaint yourself with the piece you plan to purchase — and enjoy. “There’s nothing wrong with wearing historic pieces, as long as you understand why you wear it and the significance behind it,” Siegel says. And what’s more, a proper understanding of its heritage might even be appreciated beyond the owner’s lifetime. “You become a student of the art, and when you pass it down to family members, you share the history that comes with it.”

No Comments