08 Jul In the Studio: Among the Cottonwood Trees

It would only make sense that a cowgirl who was married on horseback would also conduct an interview atop her mare. And why not, when the temperatures are in the 70s, the sky is a cloudless blue, and there’s a need to check the irrigation system anyway? That cowgirl would be Star Liana York, a horsewoman and artist who sculpts the people, animals, and environments of the Southwest.

Three years ago, on her ranch in Georgia O’Keeffe country, York married longtime friend Greg Russell, whom she’d met 28 years ago while playing polocrosse in New Zealand. A horse trainer by profession, she had helped him acquire employment in America with her neighbor, who was also an artist and horsewoman.

Rich Welding and Fabrication, in La Mesilla, New Mexico, created the entry gate from one of York’s drawings.

Today, the couple works side by side. The ranch pushes up against the Santa Fe National Forest in the Chama Valley, a place that was home to the Pueblo peoples who built villages, planted farms, and hunted wildlife there for generations. The rich agricultural heritage of the area is due in part to the Rio Chama. Acequias, or irrigation ditches, draw water from this river and channel it to nearby pastures, orchards, and farms. This is what York is monitoring on horseback, making sure that water is flowing into what she calls the Orchard Pasture and then the Hawk Pasture.

The Hawk’s Pasture, named for a nest found there, provides green grass for York’s horses, Stella, Redford, Shyloh, Zena, and Jett.

Alongside one of the acequias is York’s studio, built 15 years ago. Here, she creates bronzes that have earned her exhibitions in museums and galleries across the U.S. Her subject matter is always something close to her heart. For a time, it was life-like depictions of Native Americans. And the animals she sculpts are favored by collectors, running the gamut from prehistoric to contemporary creatures; her Mares of the Ice Age, in particular, has gained widespread popularity. Also especially touching are the nods to motherhood, as seen in a pair of donkeys, a mare and her jennet, and a mother lynx with her litter.

York and her dog, Rosebud, pause to take in the scenery in front of the barn that houses her molds.

As York rides on, she shares how she and her husband are working to reclaim the bosque — a grove of trees alongside the river that’s valued for its abilities to preserve the soil — on their 40-acre ranch. “We are working with soil conservationists to reclaim the bosque by removing invasive plants that were introduced, such as the Russian olive,” York explains.

Riding through the area called the Studio Pasture, she explains that the acequia running alongside it is the second oldest in New Mexico, and that it runs from spring to fall. “I love my studio, not only for the sound of the water, but because it attracts a lot of wildlife — raccoons and ravens, magpies and coyotes, as well as fox and badger,” she says. “I often roll my sculpture stand out on the balcony to work by the water. I feel very blessed to work here.”

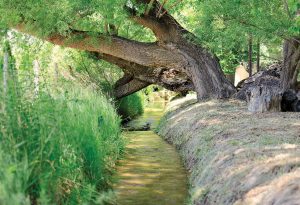

A giant old cottonwood stretches across the acequia on York’s 40-acre ranch.

York’s studio was built with Rastra block, or insulated concrete forms that fit together somewhat like Legos, don’t require mortar, and have an insulation factor akin to adobe. Generous windows with indirect light look out onto the acequia and beyond. Its ceilings are high, purposefully so, for creating monumental-sized sculptures.

From the studio, a footbridge crosses the acequia leading to the barn, a bunkhouse, and a round pen. To the east is York’s 150-year-old home, made with the vigas and latillas one would expect to find in a traditional New Mexico adobe.

York often rolls her sculpture stands outdoors to work under the tall trees.

York works solo in her studio while her husband trains horses. But she’s quick to add that she often asks his opinion. “I have ridden horses and loved them all my life; they are the subject of many of my pieces. But because Greg works with them, he is much more present to their nuances,” she says, adding that being present is a rarity in our culture, as we have grown used to constantly changing channels, and not allowing one minute of boredom. “When I ask Greg about one of my pieces, he is genuinely present, because you have to be that way with horses — even well-trained horses, like this one I am sitting on,” York says.

- Sacred to Native Americans, the bison represents healing for many tribes and nations. York’s piece Big Medicine was created to honor them.

- The artist’s interpretation of wild animals in Fox Den and All Legs shows their gentler side.

During the COVID-19 pandemic, the artist found herself thinking about subjects for her sculptures. “I don’t know where it came from, but as this whole pandemic started to look scary, I chose to do this white buffalo, not just any buffalo. It had to be a white buffalo. As a symbol of Native American culture, buffalo provided shelter, clothing, and food. But a white buffalo, whose chance of being born is one in 10 million, is celebrated as a sign of hope. Hope and belief that the future would be better.”

Appearing in a natural setting, York’s sculpture Owlette seems almost real.

Pondering the pandemic, York also began creating baby animals of various species. “I did bob kits and coyote pups, perhaps because it was like a sense of renewal. It just felt like the right thing to do,” she says. York speaks of the frailty and innocence of coyote pups, yet when they begin to play, a certain toughness prevails. “It’s survival. Right from the start, they learn to be tough, as is called for in wild animals. Perhaps I sculpted babies because, as cultures and tribes have been decimated by wars and starvation, their hope was in their children. I think our hope lies there, too,” she says.

- A wedding gift from her husband, this treehouse serves as a getaway for the couple.

- The adobe home, built on a natural rise on the land, is said to house the ghost of its original owner. If so, his ghost is benevolent, York says. “I have always felt safe and at peace here,” she adds.

As York rides to close the gates of the acequia, she speaks with enthusiasm about plans to spend the night in the treehouse her husband built for their wedding, when his family came from New Zealand and England and filled up their bunkhouse and main house. Across the big Orchard Pasture, the treehouse is in the bosque along the river, in a big, old cottonwood. “It’s romantic because it’s right on the river,” York says. “It’s actually just glamorous camping — no electricity and no water. We’ll leave the windows open all night, and it will be like camping on our own 40 acres.”

The original two-room structure, where the kitchen and dining room are, is well over 100 years old. York says the adobe has been added on to over the decades so that it’s tripled in size.

No Comments