08 Jul Of Light & Shadow

When Utah artist G. Russell Case paints the Southwest desert, he explains that his purpose as an artist is not to seek glory or renown for himself but merely to celebrate the beauty of nature and his reverence for creation.

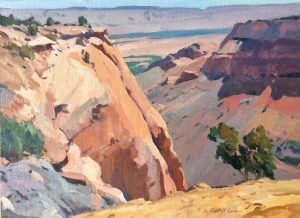

A pair of recent paintings provide good examples. In Slick Rock Canyon (2020), Case uncannily captures the changing light, but even more striking is how he invests the geologic surfaces — the stones themselves — with undeniable life. Beneath those strata of ancient rock that define the Southwest and its soaring mesas and plunging canyons, Case captures a sense of vibrancy through hard lines and simple shapes, a technique that imbues the land itself with as much life as the sage and the trees. He achieves a similar effect in Navajo Skies (2020), with both cliff faces and human forms viewed from a distance. It’s an impressive accomplishment to render the substance of geologic form with paint on canvas, but to be able to convey the rock itself as a kind of living entity is something else again.

Rain Dance | Oil on Canvas | 30 x 40 inches

Born in the 1960s, Case still lives only a few miles from Brigham City, Utah, the town where he was born and raised. His father, Garry Case, was also an artist, and between growing up in a house full of premium Southwestern art and an acquiring an education in the noted art department at Utah State University, Case established himself as one of the West’s premier painters relatively early, though at the start his medium was exclusively watercolor.

“I started collecting him 25 years ago,” says Mike Edson, a retired radiologist. “I introduced him to [collector] Jeff Mitchell, whom I knew from the C.M. Russell Museum up in Great Falls. We loved the watercolors, but encouraged him to move into oils.”

Both Edson and Mitchell found Case’s mastery of composition captivating. “The landforms and features really pop from the canvas,” Edson explains. “He’s a true painter, not an illustrator.”

Slick Rock Canyon | Oil on Canvas | 12 x 16 inches

Mitchell elaborates on how Case’s oil work has shifted over time. “His paintings have always had a consistent mastery of composition, but in his most recent work, the compositional elements have become tighter, more refined,” he says, adding that the new canvases also employ more impasto and richer colors. “Russell has become a master of mixing colors that are difficult to capture; colors that are even brighter perhaps than they appear in nature.”

Consider one of his most recent paintings, Rain Dance (2020), wherein a single Navajo shepherd stands before a distant table of ancient and striated rock, culminating in a mesa. The vertical blocks of shade and color set off the foreground almost as an afterthought, and yet, the eye is invariably drawn through the layers of rock laid down over millennia to rest on the humble human figure dwarfed by the landscape. Case may be a master of composition, but not just in the architectural sense of arranging elements reflective of the Golden Mean; he also composes a kind of geological narrative that draws the eye heavenward, up the flanks of a mountain careening toward a primordial storm.

Case’s recent work reflects the reverence the painter has for the natural world, a reverence that extends to the way the artist talks about art itself. “My job as a painter is to create an interesting painting,” Case says. “I’m not duplicating a scene. My job is to abstract the elements of what I find in nature and distill beauty from the world.”

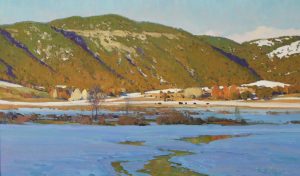

Closing Act | Oil on Canvas | 18 x 30 inches

In fact, Case is among the few artists in this postmodern age who doesn’t hesitate to zero in on beauty as a fundamental element of a painting. “Is there a common concept, a universal truth out there that is reflected in the way we relate to beauty, or is it all subjective?” he asks. And in the same breath, he supplies an answer: “I believe there is something universal about beauty, something outside of us that makes it universal.”

Case may be reticent when it comes to talking about his career and the impressive success he’s achieved, but he’s happily voluble on the connections between art and philosophy and theology. “When I see beauty in nature, I want to reproduce it,” he says, echoing the philosopher Ludwig Wittgenstein, who remarked that, “When the eye sees beauty, the hand wants to draw.”

Case has two upcoming shows, the first at Mockingbird Gallery in Bend, Oregon, where he’ll be part of a four-artist show that opens August 7 and runs through the month. Gallery owner Jim Peterson describes Case’s work as “poetic,” pointing out that as a great plein air painter, he “understands how to record the atmosphere, colors, and light that are out in the field. He becomes a student of nature and a great observationalist in the process. He also possesses the artistic strength to know what should be included in his paintings and what other inessential elements can be eliminated or edited out. The resulting works are pure, uncluttered, and captivating.”

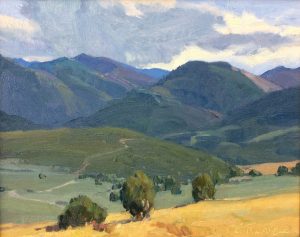

Clearing Rain | Oil on Canvas | 8 x 10 inches

More than one critic has called Case “the Maynard Dixon of the 21st century,” but both Mitchell and Peterson note that, while Case has studied his predecessor, his work distinguishes itself. “They paint the same regions, and both had intense affection for the Southwest, but if you look closely, they have noticeably different ways of handling the colors and the light,” Mitchell explains. According to Peterson, Case falls in the liminal space between impressionism and realism. “It’s realism, but not photorealism. There’s nothing fussy about these paintings. The realism derives from his powerful use of light and shadow.”

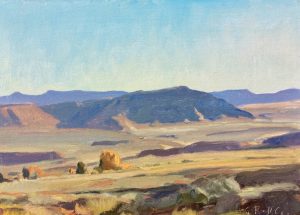

A great example of what Peterson refers to can be seen in Navajo Skies. The compositional elements are typically astounding: the range of colors, many of them so subtle as to be nearly imperceptible at first glance, match the immense scale of the scene, which pushes the envelope of the landscape beyond the realm of the atmospheric. You feel as if you can almost discern the curvature of the earth itself in the subtle arc Case has captured in the distant range of cliffs. The white of the horse’s rump is in perfect balance with the cottony phalanx of clouds overhead, just as the yellow trousers of a figure to the left leads the eye naturally across the dry wash to the oasis of cottonwoods set in the distance. The arrangement of color on the canvas reflects the more abstract and natural arrangements of the desert elements themselves: a splotch of sea green sage corresponds to the lavender shadows cast on the red rock, for example. Few artists have the power to invest brute rock and sky with the subtle animism Case achieves.

Looking West | Oil on Canvas | 9 x 12 inches

Case’s work will also be featured in a show at Astoria Fine Art in Jackson Hole, Wyoming, September 1 through 10, which owner Greg Fulton is calling Ode to Autumn. Fulton has represented Case in his gallery for a decade. “Russell is one of the best and most respected artists of the Southwest,” he says. But Fulton is quick to point out that Case’s mastery of the landscape isn’t limited geographically. “Russell is not limited by region or geology. This show really showcases his foray into other landscapes, other geographic regions beyond Utah, and features the vibrant colors of fall,” Fulton explains. “Russell’s name has been synonymous with ‘Southwest art,’ but his talent is rather broad. Any landscape rendered by Russell is going to be definitive.”

Critics and collectors alike emphasize the humanity of the artist. “He’s just a great, warm human being,” Mitchell says. “He exudes a humility and reverence for people and the land that really is humbling.”

Peterson, with Mockingbird Gallery, agrees with this characterization. “If I were to describe Russell Case in a word, it might have to be ‘authentic.’ He’s a true artist who has worked hard and found his own voice. You can walk into a gallery of strong painters, and Russell’s work will always stand out.”

No Comments