08 Jul Wanderings: National Treasures

A collection of grand structures within the national parks pays tribute to the pioneering architects who embraced the harmony between rustic design and first-class comfort. Many of these structures have been restored to meet modern building criteria, and adventure travelers who favor wilderness luxury over camping can savor the experience of a glowing Golden Gate Bridge at dusk or a welcoming sunrise at the rim of the Grand Canyon from one of these architectural wonders.

During the early decades of the 20th century, park accommodations were limited and unrefined, and to help attract tourists, railroad executives gambled by erecting extraordinary lodges. The resulting collaborations between nature and architecture are on full display at select national parks and are among some of the most exclusive resorts in the world, despite the fact that many don’t offer air conditioning or, perhaps, an internet connection. These buildings are an added bonus when exploring one of America’s “crown jewels.”

The inn is named for the famous Old Faithful Geyser, which has erupted every 44 minutes to two hours since 2000.

Old Faithful Inn, Yellowstone National Park

The National Park Service (NPS) was established in 1916 to protect natural and cultural resources in the U.S. On occasion, the two collide, as they did in the Upper Geyser Basin of the country’s first national park, Yellowstone, founded in 1872.

Of the park’s 500 geysers, the highly predictable Old Faithful, which erupts every 44 minutes to two hours, is within sight of architect Robert C. Reamer’s Old Faithful Inn. The rustic lodge was built in 1904 atop a foundation of rhyolite, the rock produced by Yellowstone’s volcanic eruptions. Reamer and 40 laborers also used 500 tons of this native stone for the 85-foot fireplace in the main lobby, as well as locally-grown lodgepole pine trees (bark intact) to forge one of the largest log structures in the world. This style of building, which appears to grow from the bedrock, ignited the architectural style called National Park Service Rustic, or “parkitecture,” and was later adopted by other NPS lodging facilities.

The centerpiece of the towering main lobby is a massive rhyolite fireplace and a hand-crafted clock made of copper, wood, and wrought iron. Photos courtesy of Xanterra Travel Collection

The 327-room Old Faithful Inn (typically open May through October) was constructed in three major phases: the 1904 original section (the “Old House”), followed by the east wing in 1913, and the west wing in 1927. Upon entry to the asymmetrical Old House, containing many original furnishings, one’s focus immediately shifts upward to a 92-foot-high gabled roof, surrounded by two levels of log balconies and a twisting stairway that leads to the “Crow’s Nest,” a separate small landing near the roof where musicians used to play for guests during the inn’s early days. Far below, the lobby was conceived in a grandiose style with the intent of inspiring guests to gather and share their daily experiences. Still without WiFi, human interaction is very much encouraged at this National Historic Landmark.

Mary Colter in Grand Canyon National Park

Located next to the El Tovar Hotel, Mary Colter’s Hopi House is a large, multi-story building of stone masonry. The multiple roofs are stepped to reference Pueblo architecture, and the tiny windows allow only the smallest amount of light into the building to limit sun exposure.

Depending on the source, the Grand Canyon has been a work in progress for anywhere between 5 million and 70 million years. What’s not disputed is the influence of architect Mary E.J. Colter, who designed six structures within the geological wonder.

As one of few women working in a male-dominated field during the early 1900s, Colter was a visionary who broke with European architectural tradition by blending Mission Revival, Spanish Colonial, and Native American design styles, and relying heavily on local natural resources. That was Colter’s gift: seamlessly crafting buildings into their indigenous environs.

The Lookout Studio was built in a location where visitors could view the Grand Canyon from its precipitous edge. Colter designed the parapet rooflines and stone chimneys to mimic the irregular shapes of the surrounding bedrock.

Her first Grand Canyon endeavor, the Hopi House (1905), modeled after the 10,000-year-old Pueblo dwellings of the Hopi, sits adjacent to Charles Whittlesey’s celebrated El Tovar Hotel (1904) on the edge of the South Rim. Throughout the next several decades, Colter executed plans for Hermit’s Rest (1914), Lookout Studio (1914), Phantom Ranch (1922), Desert View Watchtower (1932), and Bright Angel Lodge (1935).

With months of advanced planning, Grand Canyon visitors can stay overnight in two of Colter’s structures. Nestled between the inner canyon walls on the Colorado River’s north side, and the only lodging facility below the canyon rim, the legendary Phantom Ranch was constructed with on-site fieldstone and rough-hewn wood. If you want to be one of the fortunate 90 nightly guests staying in one of the two- or four-bedroom cabins, be prepared to either hike, ride a mule, or raft the Colorado River to get there.

Designed by Colter and built on the edge of the Grand Canyon, the Desert View Watchtower was patterned after structures found at Hovenweep and the Round Tower of Mesa Verde in Colorado. Photos courtesy of Xanterra Travel Collection, grandcanyonlodges.com

Colter’s other lodging masterpiece, Bright Angel Lodge, is a National Historic Landmark featuring 90 cozy lodging units and a remarkable “geological fireplace” in the History Room, with rocks arranged from ceiling to floor in the same order as the geologic strata along the Bright Angel Trail down the canyon wall.

Ahwahnee Hotel, Yosemite National Park

The Ahwahnee Hotel seems small in comparison to the towering rock walls surrounding it.

One year before architect Gilbert Stanley Underwood stamped his imprint along the Grand Canyon’s North Rim with the Grand Canyon Lodge, he brought his rustic style to Yosemite National Park with the Ahwahnee Hotel in 1927. Now a National Historic Landmark, this grand structure offers proof that striking architecture can reinforce the most wondrous of settings.

Orchestrated by Underwood in a meadow on the east end of Yosemite Valley, beneath the granite cliffs of Royal Arch, the Ahwahnee features an asymmetrical design with three wings boasting 97 rooms, plus numerous staggered balconies and large windows to showcase the sweeping views of Half Dome, Glacier Point, and Yosemite Falls.

In creating the 150,000-square-foot hotel, Underwood took great care in choosing materials and their treatment. For instance, the 5,000 tons of stone set in the walls were weathered granite, a treatment that became standard NPS practice in rustic buildings wherever masonry was used. And the exposed concrete, covering 1,000 tons of steel, was designed to imitate wood in color, form,

and texture.

Inside the lobby at the Ahwahnee, visitors will find cavernous ceilings adorned with beams, colorful stained-glass windows, Native American tapestries and baskets, Turkish kilim rugs, and Yosemite-inspired 19th-century paintings depicting the park’s waterfalls and giant sequoia trees. Photo courtesy of Aramark Leisure

The principal significance of the Ahwahnee may lie in Underwood’s rustic architecture, but the interior, with its towering ceilings, massive stone fireplaces, intricately hand-stenciled beams, and handmade stained-glass windows, was enhanced under the direction of Phyllis Ackerman and Arthur Urban Pope, who drew on influences from Art Deco, Middle Eastern, Native American, and Arts and Craft styles. Daydreamers are welcome to luxuriate in the expansive dining room as light pours in through the 25-foot-high windows.

Many Glacier Hotel, Glacier National Park

Partially renovated in 2016, the secluded five-story Many Glacier Hotel sits majestically at the base of Mount Grinnell on the shores of Swiftcurrent Lake inside Glacier National Park.

Considering Montana’s harsh winter conditions, it’s a wonder that it took only one year for the Great Northern Railway to construct the Swiss-style Many Glacier Hotel, situated in the northeastern quadrant of Glacier National Park. And despite its quick construction, soon after the doors opened on July 4, 1915, architectural historians judged the lodge a masterpiece, as quintessential an example of rustic architecture as Yellowstone’s Old Faithful Inn, Grand Canyon’s El Tovar Hotel, and Yosemite’s Ahwahnee.

As quickly as the five-story, 140,000-square-foot hotel was crafted along the shore of Swiftcurrent Lake from the plans of architect Thomas McMahon, it took 13 years (2004-2017) for the architectural firm Anderson Hallas to rehabilitate the 214-room hotel after it was threatened with closure due to decades of climate-induced damage and dire interior conditions, including failing pipes, faulty wiring, and compromised framing.

From an aerial view, Many Glacier Hotel is surrounded by the high peaks of the Lewis Range.

This multi-phased, $40-million project entailed implementing NPS requirements for quality control, sustainability, and integrated design principles, along with reinstating some iconic features, such as a classic double-helix staircase, once removed in the 1950s to make room for a gift shop, and replacing the Asian-inspired light fixtures that were once prominent in the lobby.

Surrounded by scenes of nature, including our planet’s endangered glaciers and pyramid-shaped Grinnell Point, the once-heralded “Gem of the West” has returned to its rustic grandeur and earned its spot on the National Register of Historic Places.

Architect Thomas McMahon designed the hotel in the early 1900s. Photos courtesy of Xanterra Travel Collection

Cavallo Point Lodge, Golden Gate National Recreation Area

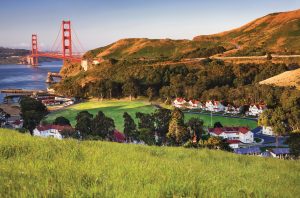

At the pre-WWI Army post of Fort Baker, within the Golden Gate National Recreation Area, Cavallo Point Lodge is the archetype model for transforming a century-old Army barracks into upscale resort accommodations, with the sweeping vistas of the San Francisco skyline and iconic Golden Gate Bridge serving as the final flourishes.

Cavallo Point Lodge’s new rooms feature sustainable design with solar power, radiant heat floors, and renewable materials.

By undertaking the project, the San Francisco-based Architectural Resources Group (ARG) sustainably restored 21 structures that were built between 1901 and 1915 and were designed in the Colonial Revival style, with large, stocky symmetry and classical elements, such as columns, wrap-around porches, and decorative windows. The buildings are clustered around the main parade grounds and harbor, and nearby, there are a number of historic gun emplacements, plus trails and forested areas ascending from San Francisco Bay.

When Cavallo Point Lodge opened for occupancy in July 2008, ARG had reinvigorated all 68 rooms and suites inside these historic structures, featuring expansive foyers, authentic tin ceilings, fireplaces, front porches, and panoramic windows to take advantage of the views. To accommodate more guests, San Francisco-based Leddy Maytum Stacy Architects conceived an additional 74 contemporary rooms, incorporating radiant heat floors and renewable materials to earn LEED Gold certification.

Situated on the site of a former military base, the lodge offers eye-popping views of the Golden Gate Bridge.

Given the quick drive to world-renowned Sonoma and Napa Valley wine country, it’s no great surprise that one of the modern amenities integrated into each room is a wine dispenser. The option to pour a glass of vino in the comfort of your room, while sitting next to the fireplace and staring through floor-to-ceiling windows, add to this memorable visit.

Cavallo Point Lodge’s 68 historic rooms and suites once served as officers’ quarters for Army personnel. The restored brick buildings feature expansive foyers and staircases, authentic tin ceilings, fireplaces, panoramic windows, and spacious front porches. Photos: Kodiak Greenwood

No Comments