05 Nov An American Icon

On a sticky, hot afternoon in July 2016, painter Dean Mitchell arrived at the White House at the appointed time, made his way through security, and into the air-conditioned foyer where curator William Allman greeted him. Genial and welcoming, Allman guided Mitchell past portraits of former presidents while the two discussed the artistic merits of each.

Finally, they turned down a short hall, at the end of which was the Oval Office. Mitchell drew a breath and wondered, was this for real? How did he, a man born into abject poverty in 1957 and raised by his grandmother in Florida, get summoned to the White House to meet with the first African American president of the United States?

Mitchell stepped into the bright, sunlit room at the end of the hall. President Barack Obama and First Lady Michelle Obama crossed the floor, shook his hand, and introduced him to Thelma Golden, the other curator helping them select the artist who would paint the president’s official portrait.

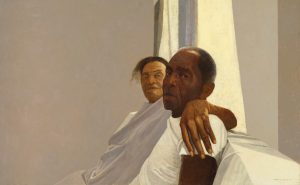

Out of Service | Acrylic | 18 x 30 inches | 2018

Nervous, yes, Mitchell was that. And excited, of course — he was there on the recommendation of the National Portrait Gallery, and he was one of four artists being considered. But more than anything else, he felt as though he had stepped into a surreal version of his life.

“People told me I’d never make it as an artist,” Mitchell says. “Art was not something anybody thought a young Black kid growing up in the ’70s in the rural South could make a career out of.” In fact, when he told his mother of his plan, she looked him in the eye and said, “Boy, you done lost your mind. Black people do not have the disposable income for this kind of thing. This is white people stuff, baby.”

She was protecting her only child, of course. In the small town where Mitchell grew up and spent every free moment teaching himself to draw, the reality was much different than his dreams. There was school, and then work in the tobacco fields and packing houses; terrible, filthy work that left his hands cut and his young body bone-weary. Worse yet, the plants were coated in pesticides and, often while he and the other Black workers were still in the fields, crop dusters would fly overhead, coating them in more of the noxious yellow chemicals.

Sam & Dollie | Oil | 30 x 48 inches | 1995

In middle school, however, Mitchell found a champion. Tom Harris, one of his teachers, believed in Mitchell’s talent and that of several other young Black kids in the school. Harris and his wife, Betty, submitted the students’ work to competitions and drove them to exhibitions, exposing the boys to the larger world of art. “We were the only Black people at those shows,” Mitchell says, “and here was this white gentleman that was taking us. He was hated by the white community and the Black. They called him and his wife ‘nigger lovers’ and all kinds of things for taking us to those shows.”

Despite the odds, Mitchell persisted and landed at the Columbus School of Art and Design, where he graduated with degrees in graphic design and advertising. He took a job at Hallmark Cards in Kansas City, Missouri, soon after. During the day, he worked as an illustrator, but in the evenings, he painted and entered fine art competitions — like Harris had helped him do years before — and he started winning.

At first, the other illustrators at Hallmark were happy for him, albeit incredulous that this young Black upstart thought he could actually become a fine artist by entering competitions. But when the prize money began to mount up, along with recognition and acclaim, the atmosphere changed. Finally, Mitchell’s supervisor told him the competitions were a conflict of interest, and he was fired.

Jagged | Watercolor | 30 x 22 inches | 2020

In hindsight, losing that job was the best thing that could have happened. Mitchell, then in his mid-20s, was making several thousand dollars a month from competitions — much more than he had made at Hallmark. Newspapers started printing his successes, and a critic in Denver, Colorado, sang his praise when reviewing his work at the invitational Artists of America show. And then, The Christian Science Monitor came calling, wanting to do a feature on the young artist who was painting Black Americans with such dignity. That article landed on the desk of the president of Kansas State University, who’s wife called Mitchell’s gallery in Kansas, told the director they were building a new museum at the university, and would Mr. Mitchell consider creating work for their inaugural exhibition?

It would be great, right here, to tell you that Mitchell’s career took off at this point, that it was smooth sailing, that his art broke through the barriers of racism to shine a revealing light on poverty and hardship across this country, but that wouldn’t be accurate. He did have that show at Kansas State University, which led to more shows and galleries — some that worked, others that didn’t.

One exhibition stands out as an illuminating example of the uphill battle Mitchell faced in the American art scene. The show titled Black Romantic was held at the Studio Museum in Harlem in New York City in 2002 and featured 30 Black painters known for their figurative work. It was curated by Thelma Golden — the same curator in the Oval Office with the Obamas that July day in 2016.

Rough Neighborhood | Watercolor | 22 x 30 inches | 2019

When the invitation for Black Romantic arrived, Mitchell was already a well-established artist, selling work internationally and participating in exhibitions across the country. And yet, in the catalog essay Golden disparaged the artists she had selected. She wrote that she was “physically unsettled” by what she perceived to be the “overwrought sentiment” of the art. She “shuddered at the crass commercialism” and the “bombastic self-promotion.”

The New York Times art critic Michael Kimmelman called her out on it. But first, he spotlighted Mitchell’s art, writing: “Mr. Mitchell’s works are subtly tuned character studies with an eye toward abstract form and charismatic light. Mr. Mitchell is a virtual modern-day Vermeer of ordinary Black people giving dignity through the elegance of his concentrated touch.”

Kimmelman observed that in her essay, Golden “labors to distance herself from the work in the exhibition, seemingly worried about displaying unfashionable artists without establishing her art world bona fides and without pigeonholing what these painters do as outsider art or acceptable kitsch or a conceptual conceit.”

“I was never Black enough,” Mitchell says without malice as we talked about that show and the afternoon in the Oval Office when he saw Golden there and knew, in that moment, that he would not be selected to do Obama’s portrait. “Black people have a certain idea of what Black art is, that it’s all about the struggle of being Black in America. My struggle is: I want to be an American painter. But I will not be defined by social constructs that are dehumanizing. Racism exists in multifaceted layers and is rife with generational pain and economic disparities. What I can do is lend my talent, my heart, and my hands to show people we are all human.”

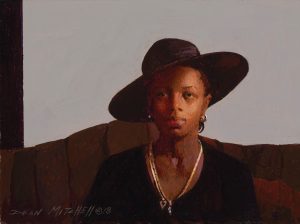

Carolyn | Acrylic | 5.25 x 7 inches | 2018

It would have been incredible to paint the president’s portrait, but then again, Mitchell isn’t sure he’d have liked all the hoopla. He is, after all, an artist whose life’s work is about ennobling the downtrodden, giving voice to the pained and the quietly resigned. He affords careful consideration to those whom the rest of the world overlooks. Woven throughout are the layers of his own life from the tobacco fields and the racial slurs to the well-meaning Black artists who told him not to let magazines publish his picture because then people would know the color of his skin.

And yet, like the people he paints, Mitchell has persevered, taking the subject matter he knows intimately and honoring it with his tremendous ability. “I do these paintings because I want people to feel the humanness of others, so that they look beyond skin color. I think that’s how an artist knows he’s hitting something powerful in the work, something beyond technique, when you can touch people in that way. It’s a lot deeper than just pigment on a surface.”

Before Mitchell left the White House, he was able to take a picture with the president and First Lady. He keeps that photo on his phone so that when he gives talks to school kids in poor rural communities in the South and tells them to chase their dreams, he has proof that it’s true: Anything is possible.

No Comments