08 Nov A Living Tradition: Luis Tapia

NOT MANY WORKING ARTISTS CAN CLAIM A DIRECT CONNECTION to an artform that’s hundreds of years old, but Luis Tapia continues to give new relevance to the art of the santo, revitalizing a form of Chicano religious iconography that dates to the turn of the 17th century in New Mexico to make powerful statements about contemporary American politics, religion, and social issues.

NOT MANY WORKING ARTISTS CAN CLAIM A DIRECT CONNECTION to an artform that’s hundreds of years old, but Luis Tapia continues to give new relevance to the art of the santo, revitalizing a form of Chicano religious iconography that dates to the turn of the 17th century in New Mexico to make powerful statements about contemporary American politics, religion, and social issues.

As a self-taught artist and activist from Santa Fe, New Mexico, Tapia’s works have been internationally exhibited and collected. His santos inform viewers about the Chicano and Nuevomexicano experience, employing one of the oldest traditions of Latino and American regional art.

The first santeros worked in Spain, carving religious mannequins of Catholic figures — Christ, Mary, saints, and angels — which devotees would adorn with expensive and ornate vestments. Santos came to New Mexico with the first Spanish settlers in the late 16th century. New Mexicans began to make these objects of devotion by hand, compensating for the scarcity of oil paints, refined tools, and silver and gold leaf in Europe by making a water-based paint from soil and minerals ground together with vegetable extracts, according to Jia-sun Tsang, senior paintings conservator at the Smithsonian Museum Conservation Institute. The practice of creating santos spread as the Spanish invaded the Western Hemisphere, and the carved wooden figures became a useful tool in the conversion of the indigenous peoples to Catholicism.

“Abuela” | Carved and Painted Wood | 15.75 x 22.25 x 12 inches | 2017 | Courtesy of the artist, photo: James Hart

“Abuela” | Carved and Painted Wood | 15.75 x 22.25 x 12 inches | 2017 | Courtesy of the artist, photo: James Hart

By 1820, a distinctive New-Mexican style had emerged,

By 1820, a distinctive New-Mexican style had emerged,  with two types of santos — the flat-panel retablo and the 3-dimensional, sculptural bulto, writes Tsang. While santos remain a vital folk art closely aligned with ecclesiastical communities in Northern New Mexico and Southern Colorado, Tapia has adapted the form to his own mode of expression, stirring controversy along the way. The result has been a singular, transcultural body of work that blurs boundaries and yet connects the dots between the religious practice, cultural identity, and the politics of oppression.

with two types of santos — the flat-panel retablo and the 3-dimensional, sculptural bulto, writes Tsang. While santos remain a vital folk art closely aligned with ecclesiastical communities in Northern New Mexico and Southern Colorado, Tapia has adapted the form to his own mode of expression, stirring controversy along the way. The result has been a singular, transcultural body of work that blurs boundaries and yet connects the dots between the religious practice, cultural identity, and the politics of oppression.

“I began [sculpting] 40 years ago in Northern New Mexico in Catholic iconography, and as time progressed, I started to find political issues involved with saints,” Tapia says. “And then in the ’60s and ’70s, when Hispanics started fighting for their rights, that all came together in my work.”

Tapia was born in 1950 in Agua Fría, New Mexico, which was then a small village on the outskirts of Santa Fe (it has since become surrounded by the growing city). His father died when he was an infant, and he was raised largely by his mother and grandmother. “When I was little, I walked with my grandmother to church every Sunday, a distance of about a mile and a half,” he says. Because his abuela spoke Spanish, that was Tapia’s first language. He came of age in the 1960s, when Chicano and Hispanic Americans were fighting nationwide for civil rights and cultural recognition.

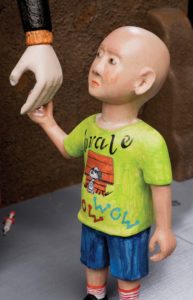

“See No Evil, Hear No Evil, Say No Evil” | Carved and Painted Wood | 31.25 x 14 x 17 inches | 2011 | Rockwell Museum, Corning, New York (2015.8), photo: Eric Swanson

“See No Evil, Hear No Evil, Say No Evil” | Carved and Painted Wood | 31.25 x 14 x 17 inches | 2011 | Rockwell Museum, Corning, New York (2015.8), photo: Eric Swanson

When Tapia first began carving santos,

When Tapia first began carving santos,  he mimicked the look of traditional figures he observed in churches and in museum collections. He quickly noticed that the colors of older figures were somber and washed out. The artist argued early in his career that historically santos exuded rich, vibrant colors, but over the centuries the vibrancy faded. Though the traditional santo art community resisted his innovative return to brilliant color, Tapia’s theory was corroborated by Smithsonian conservators a decade after he first announced it. Some contemporary santeros have since followed his lead in reinterpreting the iconography to produce effigies that are more brightly painted. “Color is a celebration,” Tapia says, a reflection of his own exuberant embrace of his Catholic culture and a motto for his approach.

he mimicked the look of traditional figures he observed in churches and in museum collections. He quickly noticed that the colors of older figures were somber and washed out. The artist argued early in his career that historically santos exuded rich, vibrant colors, but over the centuries the vibrancy faded. Though the traditional santo art community resisted his innovative return to brilliant color, Tapia’s theory was corroborated by Smithsonian conservators a decade after he first announced it. Some contemporary santeros have since followed his lead in reinterpreting the iconography to produce effigies that are more brightly painted. “Color is a celebration,” Tapia says, a reflection of his own exuberant embrace of his Catholic culture and a motto for his approach.

Yet, Tapia has integrated another provocative element into his santos: he introduces contemporary culture — often intimate expressions of political controversy — in order to draw attention to urgent issues in the Latino, and, more specifically, the Chicano community.

An example is Broken Promises (2017), a rendering of the iconic Statue of Liberty that makes a statement about immigration and the U.S. by stripping away the stately robes of Lady Liberty to reveal a body composed of faces reflective of ethnicities from all over the globe. The inscription “Freedom” hangs broken below her pedestal, and both the arm holding the torch and the hand holding her tablet have been stripped of flesh, as if she is becoming a harbinger of día de Muertos before our eyes.

“I want the viewer to contemplate the commentary, to take their own interpretation [of a work like Broken Promises],” Tapia says. “I have no preordained idea of what the work means.”

“Virgen del Camino de Sueños” | Carved and Painted Wood | 15.75 x 13 x 10.25 inches | 2016 | Collection of Curt, Christina, and Jonah Nonomaque, photo: James Hart

“Virgen del Camino de Sueños” | Carved and Painted Wood | 15.75 x 13 x 10.25 inches | 2016 | Collection of Curt, Christina, and Jonah Nonomaque, photo: James Hart

In Abuela (2017), we see Tapia’s reverence for color in vivid display, as a Marian figure merges with a grandmother against a backdrop of what James Howard Kunstler called “The Geography of Nowhere” — the fast-food marquis and gas station signs as a new part of American iconography. Critics of Tapia’s work have emphasized its liminal power, arguing that it plants itself in several cultures at once. In fact, the title of the most comprehensive overview of his work is Borderless: The Art of Luis Tapia — a title that reflects Tapia’s power to generate universal imagery and meaning out of the elements of folk art and his own Northern New Mexican culture.

In Abuela (2017), we see Tapia’s reverence for color in vivid display, as a Marian figure merges with a grandmother against a backdrop of what James Howard Kunstler called “The Geography of Nowhere” — the fast-food marquis and gas station signs as a new part of American iconography. Critics of Tapia’s work have emphasized its liminal power, arguing that it plants itself in several cultures at once. In fact, the title of the most comprehensive overview of his work is Borderless: The Art of Luis Tapia — a title that reflects Tapia’s power to generate universal imagery and meaning out of the elements of folk art and his own Northern New Mexican culture.

Tapia’s sculptures are carved in the round and meant to be viewed the same way. Abuela is a study in contrasts from every angle: from how night and day are opposed on the mural, to the mural itself facing away from the scene taking place behind it; a grandmother holds her grandson’s hand with a bemused expression on her face amid a squalid urban scene, replete with abandoned beer cans and sidewalk graffiti.

Never one to shy away from confronting controversy, Tapia’s See No Evil, Hear No Evil, Say No Evil (2011) takes on the horror of the pedophilic priests and the way in which they were protected by the church. In the sculpture, three priests depict the Buddhist principles of the title (sentiments more commonly witnessed in popular culture by three monkeys making the same gestures), denying the scandal of pedophilia in the church just as Peter denied his Lord three times “before the cock crowed.” Meanwhile, the faces of the victims adorn the pediments of a kiosk that represent the church that houses the corrupt priests. With a minimum of compositional elements, Tapia has created a complex work that compels the viewer to confront the power structures inherent in politics and religion.

“A Slice of American Pie Painted Metal” | 56 x 210 x 23 inches, 700 pounds | 2008 | National Hispanic Cultural Center Art Museum, Albuquerque, New Mexico, photo: Addison Doty

“A Slice of American Pie Painted Metal” | 56 x 210 x 23 inches, 700 pounds | 2008 | National Hispanic Cultural Center Art Museum, Albuquerque, New Mexico, photo: Addison Doty

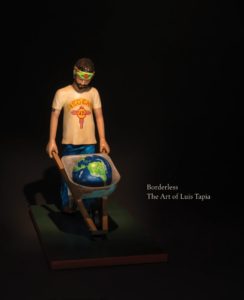

“Borderless: The Art of Luis Tapia” Book cover and detail | 2017 Museum of Latin American Art: Long Beach; distributed by University of Oklahoma Press

Even Tapia’s earlier, more traditional work exudes arresting power. Carreta de la Muerte (1986), for example, depicts an immense carved skeleton (the traditional image of Doña Sebastiana displayed during Holy Week in New Mexico) sporting real human hair and teeth. The rustic, darkened carreta provides a stark contrast to the bleached, carved bones of Death, whose exaggerated extremities are at once comedic and foreboding.

Even Tapia’s earlier, more traditional work exudes arresting power. Carreta de la Muerte (1986), for example, depicts an immense carved skeleton (the traditional image of Doña Sebastiana displayed during Holy Week in New Mexico) sporting real human hair and teeth. The rustic, darkened carreta provides a stark contrast to the bleached, carved bones of Death, whose exaggerated extremities are at once comedic and foreboding.

One of the most alluring qualities of Tapia’s work, evident in Carreta de la Muerte, is the haptic sense in which the artist remains present: The tool marks themselves suggest an enduring immediacy, as if the artist had just completed his work.

Borderless is an appropriate title for the book celebrating Tapia’s career. Though the influences of traditional santos are evident in his work, and while the subject matter of his work is largely a reflection of his own Northern New Mexican culture and its encounters with history and other cultures, Tapia refuses to allow himself to be penned in by arbitrary traditional boundaries. The imagery may be distinctly Hispanic, but his art is truly Catholic in the original sense of the word: universal.

“Carreta de la Muerte” | Carved Aspen, Mica, Human Hair, and Teeth | 51.25 x 32.25 x 54 inches, 1986 | Collection of Smithsonian American Art Museum, Washington, D.C. (1990.18), photo: courtesy Smithsonian Institution

“Carreta de la Muerte” | Carved Aspen, Mica, Human Hair, and Teeth | 51.25 x 32.25 x 54 inches, 1986 | Collection of Smithsonian American Art Museum, Washington, D.C. (1990.18), photo: courtesy Smithsonian Institution

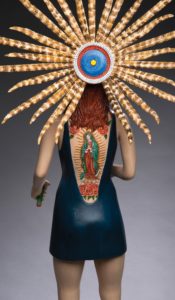

“Barrio Barbie (Azteca)” | Carved and Painted Wood | 33.75 x 9 x 16.125 inches | 2017 | Courtesy of the artist, photo: James Hart

“Barrio Barbie (Azteca)” | Carved and Painted Wood | 33.75 x 9 x 16.125 inches | 2017 | Courtesy of the artist, photo: James Hart

No Comments