08 Nov At Home with Architect Jonathan Foote

WHEN JONATHAN FOOTE DESIGNS A HOUSE, he thinks like a composer. “When I’m designing buildings,” the architect explains, “I have music going through my head. Key changes, rhythm changes, they’re really key to conceptualizing a building, especially where there are volumes of space, passages, resting points, and junctures where you make choices. It’s a celebration of the poetry of spatial movement.”

Architect Jonathan Foote has been practicing his craft for almost six decades. His career began on the densely developed East Coast, but he is best known for pioneering the place-based architecture movement in the rural Rocky Mountain West.

After almost six decades as a working architect — first in the Northeast and, since 1968, in the Northern Rockies — Foote has long known that he can trust the music, allowing it to give form to the buildings he designs and their relationship to the land on which they dwell. Since 1968, when he designed a home on his brother’s ranch in Ovando, Montana, using reclaimed and restacked homesteader cabins from that ranch, Foote’s name has been synonymous with a place-based architecture movement, in which buildings are a product of their site, are referential to the region, and engage in a kind of dance with the land. Given where he’s building — in supremely beautiful, pristine, and wildlife-rich properties throughout the Mountain West — it is a grave responsibility, one that he does not undertake lightly.

After almost six decades as a working architect — first in the Northeast and, since 1968, in the Northern Rockies — Foote has long known that he can trust the music, allowing it to give form to the buildings he designs and their relationship to the land on which they dwell. Since 1968, when he designed a home on his brother’s ranch in Ovando, Montana, using reclaimed and restacked homesteader cabins from that ranch, Foote’s name has been synonymous with a place-based architecture movement, in which buildings are a product of their site, are referential to the region, and engage in a kind of dance with the land. Given where he’s building — in supremely beautiful, pristine, and wildlife-rich properties throughout the Mountain West — it is a grave responsibility, one that he does not undertake lightly.

“The architectural language is different here,” he says. “The weather is different, the attitudes are different, the goals are different. My own view is that there should be a respect for place.”

Foote’s home is an example of the design practice he espoused, now commonplace, of saving and repurposing old buildings and making use of reclaimed materials.

Foote’s home is an example of the design practice he espoused, now commonplace, of saving and repurposing old buildings and making use of reclaimed materials.

Born and raised an Easterner, Foote fell in love with the Mountain West on a family dude ranch vacation in 1946. He then worked on ranches during summers throughout high school and college. As an undergraduate at Yale, he became interested in architecture, pursuing it in graduate school at the Rhode Island School of Design, then back at Yale, where he received a master’s degree in architecture. There, he studied under many of America’s most influential modernists — Louis Kahn, Paul Rudolph, Phillip Johnson — and had exposure to such greats as Frank Lloyd Wright. An early marriage (he was a father before he graduated from college) prompted a practical move; he worked in architecture, development, and planning in New York and Connecticut. After a second divorce, and disenchanted with some of the less-savory realities of building in the East, he headed West.

Foote first came west to work on ranches in the summers during college. He returned to compete on the cutting-horse circuit during a break from practicing architecture. Foote designed and built the reclaimed-wood indoor arena in the mid 1980s.

“I was on the cutting-horse circuit at that point,” he explains. “I packed up my horses, took a couple of shirts, a couple pairs of Levi’s, a couple pairs of boots, and put 75,000 miles a year on my truck doing the circuit. I just completely withdrew from the world I grew up in and found a world that was healthier for me.”

“I was on the cutting-horse circuit at that point,” he explains. “I packed up my horses, took a couple of shirts, a couple pairs of Levi’s, a couple pairs of boots, and put 75,000 miles a year on my truck doing the circuit. I just completely withdrew from the world I grew up in and found a world that was healthier for me.”

For a couple of years, Foote did nothing but compete, until one day he was approached at a cafe in Lincoln, Montana, and asked to teach at Montana State University (MSU) in Bozeman. (He’d taught at Yale and “loved it, just loved it.”) Foote taught at MSU from 1979 to 1989, while also designing homes for discerning clients throughout the greater Yellowstone region — clients who saw the quiet beauty and appropriateness of more modestly scaled buildings of hand-hewn timbers and local stone. Jonathan L. Foote Associates, AIA, thrived as the preservation movement took hold.

One of the secrets to his success, he says now, was that, “I understood that there was a resource out here of individuals who could build. I found these guys in the late ’60s and early ’70s, hippies who had a high IQ, a high sense of craft, and a love for what I was doing, which was creating a future out of the past and making a transition from the Old West to the New West. Their craftsmanship was key to the success of the projects.”

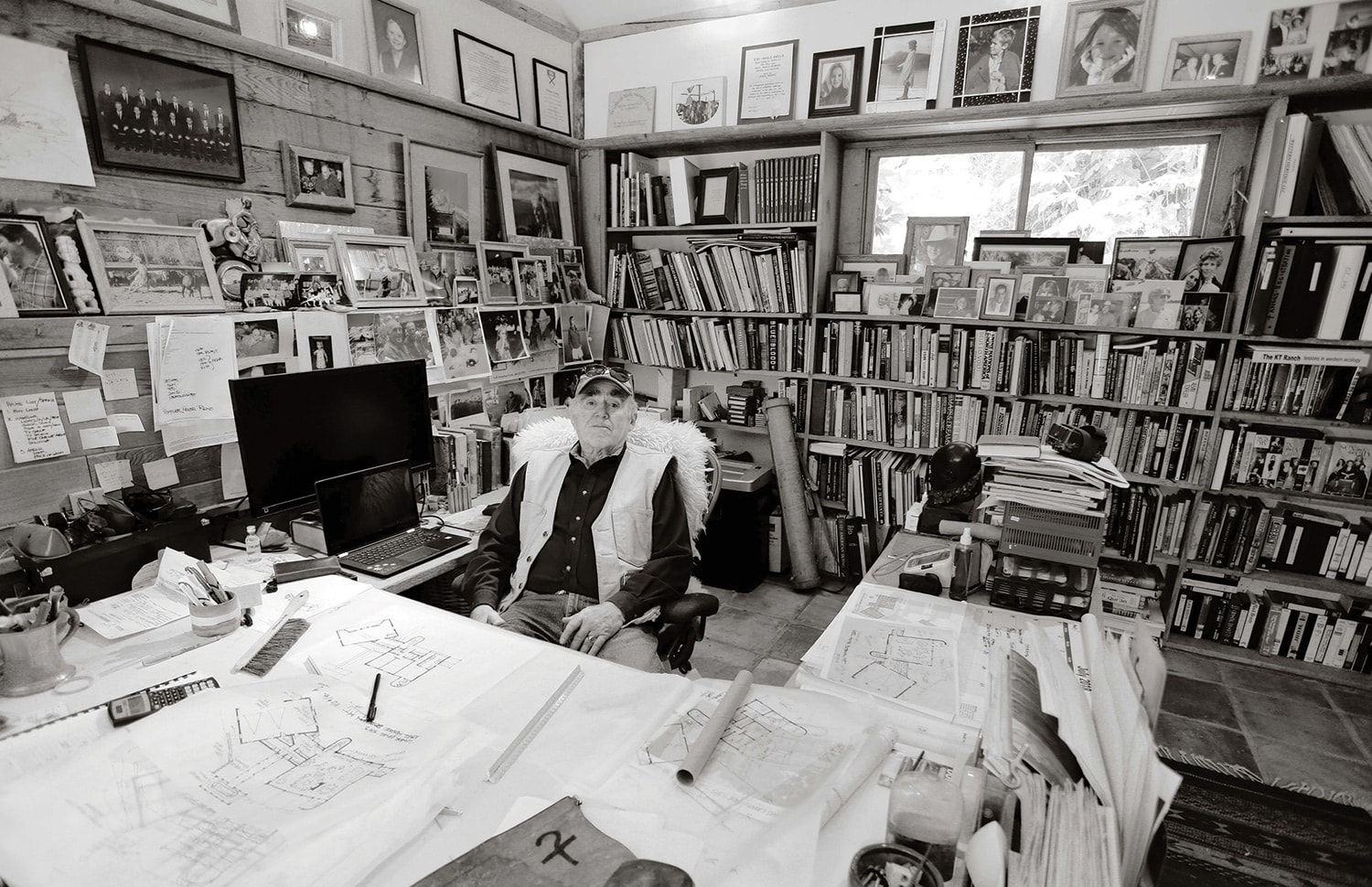

Although the architect sold his firm after experiencing a stroke, he still practices as an independent architect from his studio on the ranch. Foote wakes at 2:30 a.m. every day to start working. “At age 83,” he says, “I realized time was running short.” He creates his drawings in a space of ordered chaos, heated by a pot-bellied stove.

Although the architect sold his firm after experiencing a stroke, he still practices as an independent architect from his studio on the ranch. Foote wakes at 2:30 a.m. every day to start working. “At age 83,” he says, “I realized time was running short.” He creates his drawings in a space of ordered chaos, heated by a pot-bellied stove.

Foote and his wife, Kathy, who still competes on a world-class level in the U.S. and Canada, live in Paradise Valley, Montana.

Foote founded the construction company On Site Management (OSM) to more seamlessly execute his visions, and hired some of his most talented MSU students to work with him in his architectural practice. “In the design world,” he notes, “it’s great to work with people you don’t have to convince.”

his visions, and hired some of his most talented MSU students to work with him in his architectural practice. “In the design world,” he notes, “it’s great to work with people you don’t have to convince.”

Foote designed Western buildings and rode cutting horses — he’s been inducted into the National Cutting Horse Association Hall of Fame — until the first of two strokes, when he decided to bow out gracefully. He gave up cutting and sold his firm. Now known as JLF & Associates, Architects and Design Builders, the firm still sets a standard for beauty, originality, appropriateness, and craftsmanship.

His wife, Kathy, still competes, while Foote resumed designing 15 years ago. They live most of the year in Livingston, Montana, on a ranch with an old homestead cabin that dates back to 1906. Foote wakes every day at 2:30 a.m. to start work. The perspective from his studio, where a functional disorder reigns, encompasses grazing horses and the mountains beyond. At the moment, he’s designing multiple structures for a longtime client’s property in Belgrade, Montana.

Of his career in the Mountain West, he says, “It’s a delicate dance I’ve been doing for 40 years. I try to capture the spirit but have it be functionally effective in a modern context. I try to capture the feeling without being sentimental.”

Of his career in the Mountain West, he says, “It’s a delicate dance I’ve been doing for 40 years. I try to capture the spirit but have it be functionally effective in a modern context. I try to capture the feeling without being sentimental.”

In Foote’s buildings — timeless, quiet, beautiful, and rooted in their sites — the architect has undoubtedly achieved success while helping inspire the next generation to build thoughtfully and respect the land. And he still hears the music.

helping inspire the next generation to build thoughtfully and respect the land. And he still hears the music.

“I put together a palette of materials which respect the local vernacular, and choreograph the spatial sequences in such a way that the unique nature of the place is celebrated as one approaches, moves within, and departs a dwelling,” he explains. “Like a well-constructed piece of music, central themes are reinforced by revisitation in varying ways, the juxtaposition of images, and the volume and flow of spaces. These create subtle harmonies and contrapuntal impacts that characterize the Western experience, while walking softly on the land.”

No Comments