08 Nov In the Studio: A Renaissance Space

A vision of the mysterious light in Spanish Shawl, one of JoAnn Peralta’s most notable paintings, came to her as she was waking up one morning. The light was so purely brilliant, she felt she had to match it exactly. But she won’t reveal how she did it — not yet anyway. “When I’m in my 80s, I’ll give everything [away],” she says.

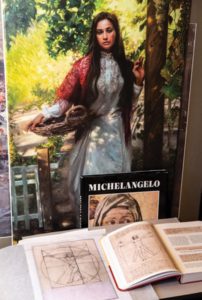

Peralta makes intricate sketches of her scenes and portraits before putting paint to canvas. Each one is in and of itself a work of art.

The walls of her small studio are ornamented with giclée prints of paintings that now hang on the walls of art collectors. She has a sales rate of 85 percent.

Intimate moments illumined by candlelight or deeply angled sun are Peralta’s strong suit, along with mastery of the figure. She’s also skilled in depicting facial expressions, eyes that communicate a willingness to be seen and perhaps to tell. Her abilities shine in portraits of children, such as a mother walking her children up to bed, subjects that could easily slide into sentimentality, in a genre derogatorily termed “feminine,” which Peralta astutely avoids.

Maryvonne Leshe of Trailside Galleries recognized the strength of her work in 2004. She took six of the eight paintings Peralta showed her into her gallery, and all of them sold. Since 2009, Peralta has exhibited at the Masters of the American West at the Autry Museum, in Los Angeles, California. And a painting commissioned by California Congressman Steve Knight, Heart of the West, hangs in the Longworth Building in the United States Capitol.

A Spanish fountain outside of Peralta’s studio is a nod to the artist’s Spanish and Mexican heritage, which is a fountain of inspiration, continually renewing her desire to paint.

A Spanish fountain outside of Peralta’s studio is a nod to the artist’s Spanish and Mexican heritage, which is a fountain of inspiration, continually renewing her desire to paint.

“They’re lovely paintings,” remarkes Leshe. “Well composed, well painted, and I think the reason they sell well is that there is that intimate relationship she shows many times in the family setting.”

Never satisfied with her skill level, Peralta is always striving for mastery, looking especially to painters like Joaquín Sorolla, Albert Bierstadt, and Wassily Kandinsky, among others.

The tools of her trade: beauty, paint, and, though she doesn’t explicitly say so, there are many indications that faith plays a role in her life and creativity.

Her studio may be a prefabricated barn, but nothing remotely prefabricated happens there. The wide, customized loft is where the artist imagines and maps out concepts. Her easel is positioned to catch the natural light. Giclée prints of a dozen of her completed works, long since sold, lean against or hang from walls. On working mornings, Rachmaninoff or Puccini plays, setting the mood for what Peralta calls her “renaissance space,” an open-hearted mindset in which everything is new, exciting, and possible. Visitors might have to knock more than once to summon her back to the world.

“I completely just try to capture the light. That’s first and foremost. I try to capture how much of the light I want to let in, and how it delineates off the first point of impact, and then falls away,” the artist says.

Many of Peralta’s works, including “Spanish Shawl,” are infused with the warm glow of candlelight. It’s an effect that injects a sense of intimacy and warmth into her scenes and portraits.

Peralta was born with a talent for drawing and painting — even her kindergarten teacher remarked on it. But she developed creative vision and technique through her own industriousness and belief in herself. Her marriage to Morgan Weistling — one of America’s top representational realism painters — has meant a life steeped in a creative sensibility. But in her new memoir, MathFace, Peralta tells readers that the journey from book cover illustrator to fine artist brought her back to herself through her ancestral roots. Curiosity about her childhood aptitude for math and geometry, and whether it might hold the key to artistic freedom, blew the doors open even wider. Delving into the methods of Spanish painter Joaquín Sorolla, one of her heroes, she examined his use of gridlines for managing space.

“I thought, ‘Let me go down that road, rather than the hit-or-miss of drawing from reference,’” she says. Soon, she had trained her mind to recognize vector lines and angles without the gridlines.

Peralta gives her ideas the space and time they need to grow and blossom. She is never in a rush. One of her paintings, First U.S. Land Patent Awarded, Dominguez Family, 1858, took four years from initial spark to finished work.

Peralta gives her ideas the space and time they need to grow and blossom. She is never in a rush. One of her paintings, First U.S. Land Patent Awarded, Dominguez Family, 1858, took four years from initial spark to finished work.

But for Peralta, accuracy of the figure, the truth of its nuances and proportions, is where great art begins. “When you know your boundaries, the boundaries create freedom. Spanish Shawl was me getting out of the way. Every language I’d learned based on angles and math had taken root, and I understood how far I could go.”

Perhaps a more momentous eureka

Perhaps a more momentous eureka moment came some years before, as she was driving down an ordinary Southern California highway, cutting through agriculture fields. Seeing the men and women laboring in the hot sun, Peralta was struck with a renewed appreciation for the life and sacrifices of her late grandmother. After immigrating from Mexico with her husband in the 1920s, her grandmother labored in the fields for years. Peralta felt such gratitude in that moment, she decided then and there that she would paint under her grandmother’s maiden name, Peralta. And then she thought, “Why don’t I paint workers in the field?”

moment came some years before, as she was driving down an ordinary Southern California highway, cutting through agriculture fields. Seeing the men and women laboring in the hot sun, Peralta was struck with a renewed appreciation for the life and sacrifices of her late grandmother. After immigrating from Mexico with her husband in the 1920s, her grandmother labored in the fields for years. Peralta felt such gratitude in that moment, she decided then and there that she would paint under her grandmother’s maiden name, Peralta. And then she thought, “Why don’t I paint workers in the field?”

Everything came together; the draftsmanship skills she had been quietly and diligently developing and the emotion of her life story. After three years of painting vineyard workers, Peralta embraced even earlier ancestral roots, which traced back to Spain and Italy, and she began exploring the wider cultural influences on California life. Some of her most ambitious paintings depict historic moments, such as First U.S. Land Patent Awarded, Dominguez Family, 1858. In exquisite detail, the painting shows the Dominguez family gathered together in their living room, examining the land patent from the U.S. government, granting the family ownership of the land that had already been given to them by Spain.

“Charles F. Lummis and the Songs of Old Spanish California, 1904” | Oil on Linen Canvas | 28 x 40 inches | California’s historical and cultural influences are important to Peralta. Charles F. Lummis, journalist, poet, and historical preservationist, led the campaign to preserve California’s missions. One of Peralta’s most successful historical paintings, “Charles F. Lummis and the Song of Old Spanish California, 1904” depicts the scene of one of his many musical gatherings.

“Charles F. Lummis and the Songs of Old Spanish California, 1904” | Oil on Linen Canvas | 28 x 40 inches | California’s historical and cultural influences are important to Peralta. Charles F. Lummis, journalist, poet, and historical preservationist, led the campaign to preserve California’s missions. One of Peralta’s most successful historical paintings, “Charles F. Lummis and the Song of Old Spanish California, 1904” depicts the scene of one of his many musical gatherings.

At a Trailside Galleries show last September in Jackson Hole, Wyoming, two avid Western art collectors expressed an interest in one of Peralta’s newest paintings, Time for Bed, in which a mother holding a lantern walks two small girls up the stairs. Bathed in soft light, the girls’ expressions and body language are gently telling; along with the textures and shadows, the work is impressionistic realism at its magical best. The next day, one of the collectors called Leshe, but the painting was gone. “He said, ‘I just kept thinking about it.’ And that’s what a painting should do,” Leshe says.

Peralta likens being married to Weistling as being together in a playground. He’s on one swing and she’s on another, and they’re holding hands, each pursuing their unique creativity yet still connected and having fun. “That’s what it feels like being married to him. He’s so much fun. The best spouse I could have picked.”

And now, someone else has joined them in the playground. Their eldest daughter, Brittany Weistling, 23, has grown into a noted artist of representational realism as well. Their youngest daughter, age 12, has announced she wants to be a doctor.

“JoAnn is young,” said Leshe. “She has a long career ahead of her. I’ve seen tremendous growth in her work over the past 10 years. They’re becoming more interesting in many aspects. They’re not just pretty paintings.”

No Comments