08 Nov Perspective: Earl Biss [1947–1998]

Artist Earl Biss was a man driven by visions and demons. He was brilliant, charming, handsome, volatile, sometimes violent and, as his friend, Hunter S. Thompson, affectionately said, “crazy as five loons.” He was also a primary catalyst in an art movement that saw works created by Native Americans move from anthropology museums to major art museums — literally transforming from “folk art” into fine art.

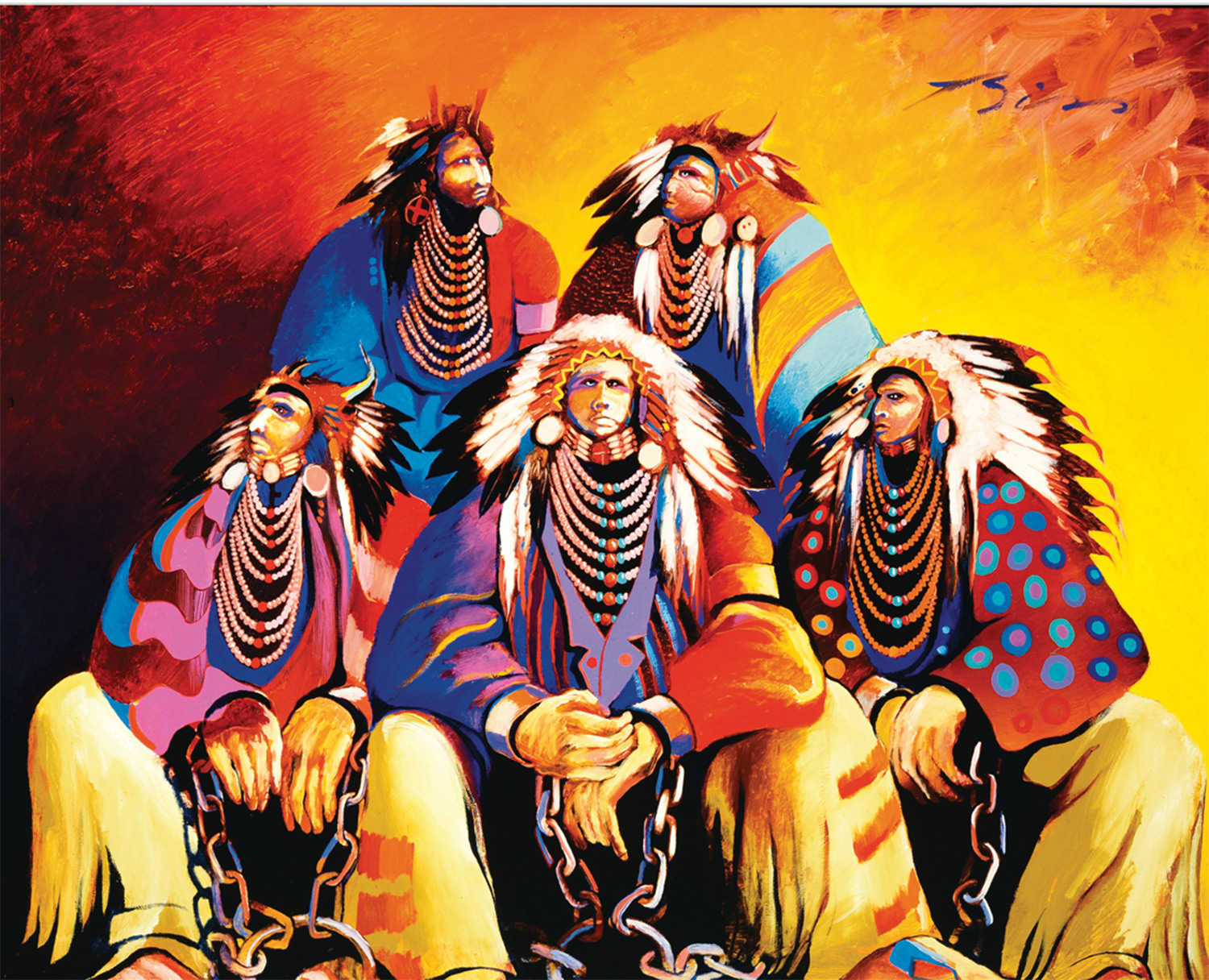

“Don’t They Know They Can’t Capture a Medicine Man?” | Oil on Canvas | 66 x 50 inches | 1984 | Courtesy of Dr. Wayne Yakes

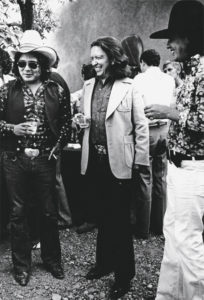

Biss (right) with T.C. Cannon (left) and Fritz Scholder, circa 1975. Courtesy of Dana Ivers

Biss carried the power, and the trauma, of his Crow heritage. He elevated his people through his depiction of them, while often undermining himself through drugs, alcohol, and risky behaviors.

Biss lived a life of urgent intensity, unconstrained by convention. He was married at least eight times and arrested far more times. Like his shaman ancestors, Biss was a shapeshifter. He moved between the worlds of Native and white, high society and the street, art and the underworld. His collectors ranged from a president of the United States to a president of the Hells Angels Motorcycle Club.

A self-described “mongrel alcohol orphan,” Biss grew up scuffling around the Crow reservation in Montana with a dog named Spot. They were often hungry, and stole food scraps and change left by tourists at the local diner. Biss learned early on to do whatever it took to survive.

He began to produce art in earnest at age 8, after a bout with rheumatic fever left him too weak to go outside and play. He received his first formal training at 12, and at 16 was invited to attend the Institute of American Indian Arts (IAIA) in Santa Fe, New Mexico.

“Early Snow on the Beartooth Range” | Oil on Canvas | 60 x 84 inches | 1986 | Courtesy of Paul and Bonnie Zueger

“Early Snow on the Beartooth Range” | Oil on Canvas | 60 x 84 inches | 1986 | Courtesy of Paul and Bonnie Zueger

Founded in 1962, IAIA offered an extraordinary program, with instructors such as Fritz Scholder and Allan Houser, who exposed students to everything from rock art to Pop Art. Biss was immersed in dance, drama, music, ceramics, and jewelry, as well as painting, drawing, and sculpture, and was pushed by friendly competition with fellow students T.C. Cannon, Kevin Red Star, Doug Hyde, and Linda Lomahaftewa.

Biss went to the San Francisco Art Institute (SFAI) on a full scholarship in 1966, but he found the coursework boring. He drifted away into the “Summer of Love,” where he had his first collision with heroin. He fell hard, hit bottom, and survived for a time by robbing stores in Chinatown.

Biss managed to clean up and start over, but he lost his second wife to an overdose. He re-enrolled at SFAI, met a fellow artist who would become his third wife, and threw himself back into painting.

“Land of the Free, Home of the Brave” | Oil on Canvas | 60 x 72 inches | 1993 | Courtesy of American Design Ltd.

“Land of the Free, Home of the Brave” | Oil on Canvas | 60 x 72 inches | 1993 | Courtesy of American Design Ltd.

After leaving school, they spent a year in Europe, haunting galleries and museums. Biss absorbed in his eidetic visual memory the composition of the Old Masters, the luminous skies of Claude Lorrain and J.M.W. Turner, the brushstrokes of the Impressionists, and the gaudy palettes of the Fauvists.

Inspired by those experiences, he set out to master the medium of oil paint, experimenting endlessly with thickening, thinning, stretching, and splattering. He called his technique “moving paint,” and often worked in manic bursts of up to seven days and nights straight.

Biss regularly painted with both hands on separate canvases using different palettes, and wielded tools from sable brushes to torn chunks of cardboard, Q-tips, brooms, and bare feet. Fueled by drugs, alcohol, and a profusion of lovers, he produced as many as 60 canvases in those marathon sessions.

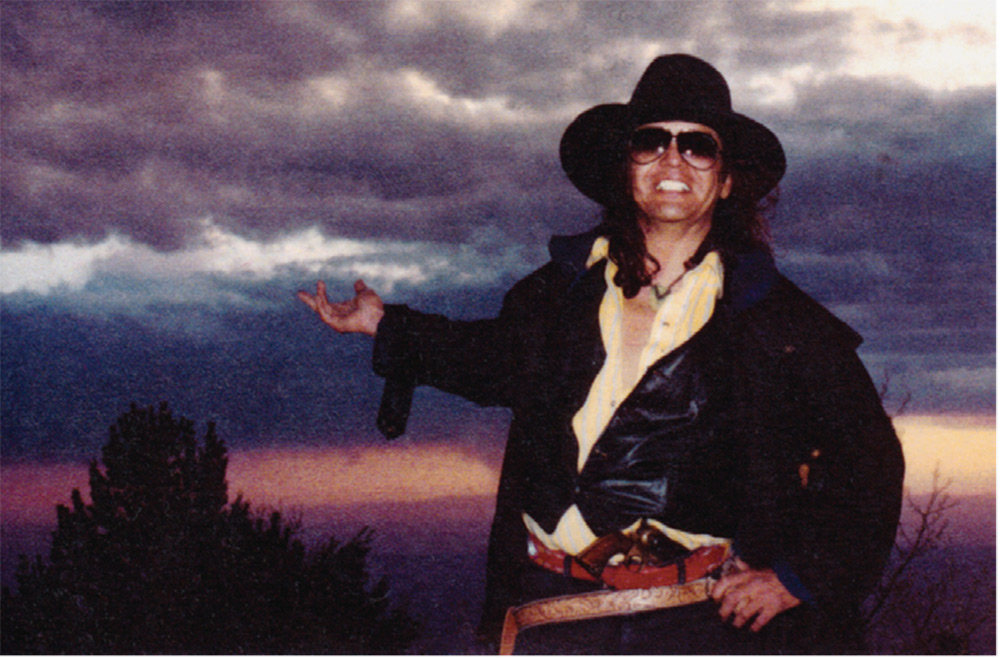

“Self Portrait” | Oil on Canvas | 40 x 30 inches | Courtesy of American Design Ltd.

Inspired by shapes lurking in the thick coastal fogs of the Netherlands, figures of Crow mythology, and his visions of the spirit world as he lay in a fever-induced coma as a child, Biss unveiled his Night Rider series in the mid-1970s. It quickly brought him representation, recognition, and a series of sell-out shows.

His new style was clearly impressionistic, but it was a type no one had ever seen before. Where earlier American Impressionists had simply applied European techniques to American scenes — especially idyllic pastoral scenes, portraits, or urban scenes such as those of the Ashcan School — Biss depicted the sweeping landscapes of the American West and the lifestyles of its first peoples. And where traditional Impressionists often depended upon the dark palettes and gestural styles of brushwork made popular by Goya and Manet, Biss added brilliant light and skies in the manner of Turner and Lorrain. He also added layers of texture beyond even those of van Gogh, creating light and shadow with impasto as well as with his palette. He was a master of negative space, creating figures by painting around them, and sometimes using sgraffito to pull out shapes.

“Riders at the Foothills with a Witching Moon” | Oil on Canvas | Courtesy of American Design Ltd.

Unfortunately, Biss’ success also brought him the adulation of art groupies and immersion in the cocaine culture that flourished in parts of the art world. He walked out on his marriage and fell deeper into drugs and alcohol.

By the 1980s, Biss was selling out shows in Europe and North America, but couldn’t stay with an art dealer or woman for long, blowing through several galleries, at least five more marriages, and countless affairs. He often ended up in jail, hiding out on the reservation, or in South America while his lawyers negotiated agreements that would allow him to return.

Biss was nomadic in the Crow tradition, even when he wasn’t on the run. He had a restless, relentless energy and moved continually, often with nothing but the clothes on his back, a .45 pistol in his belt, and a roll of $100 bills in his pocket.

Despite the circumstances of his life and the turmoil around him, Biss returned regularly to the reservation to see friends and family and dance at Crow Fair in Montana. He rode his horses in the Absaroka-Beartooth Wilderness, undertook vision quests, and planted elk teeth under the full moon in the Pryor Mountains, a place of folklore, where the “Little People” of Crow legend live.

Away from those touchstones, the outrageousness of his lifestyle boosted his career, even as it destroyed his health and relationships. He acquired a gaggle of hangers-on who continually demanded cash, drugs, and art. Biss always accommodated them, often keeping nothing for himself. He could have $100,000 in cash one day and not have lunch money the next. He lurched from chartered jets, limos, and Cadillac convertibles to beater trucks, and from champagne and lobster to beer and spaghetti.

As his personal troubles grew — including multiple seizures of his work by the IRS over his refusal to pay taxes as a political statement — Biss’ art continued to evolve. His work became more depictive, more colorful, and more political. One critic called him “the American Monet,” and another declared him the greatest colorist of the 20th century.

“Riding Below Pryor Gap with Dogs” | Oil on Canvas | 61 x 41 inches | 1998 | Courtesy of Paul and Bonnie Zueger

“Riding Below Pryor Gap with Dogs” | Oil on Canvas | 61 x 41 inches | 1998 | Courtesy of Paul and Bonnie Zueger

“Earl never lost his edge,” says Dr. Wayne Yakes, an early collector of Biss’ work based in Denver, Colorado. “I think because of the way he grew up, he knew it could all be gone tomorrow. And I think that pushed him to do the best he could always.”

At the same time, he became less and less willing to play the “iconic artist” game. He disliked going to his openings, often arriving late and leaving early, and he resisted indulging his collectors. When one asked, “What’s behind this painting?” Biss once replied, “The wall.”

Through all the ups and downs, the trauma and the turmoil, Biss stayed true to what he cared about most: He painted. He poured his hope, anger, grief, and love into his canvases. He was at work in his Santa Fe studio when he was felled by a massive stroke at age 51.

When Biss began his art career in 1955, there were still signs in the windows of museums in the American West stating “No Dogs or Indians.” By the time of his death in 1998, those same museums competed to show his work and the work of his colleagues in what had become the Contemporary Southwest art movement.

No Comments