08 Nov Rendering: Of Gardens and Great Rooms

“Right now, all our projects are for repeat clients,” architect Brian Tichenor remarks. “Is that true?” his partner and wife, Raun Thorp, asks, not expecting an answer.

A painting by Tichenor hangs in their Los Angeles office. All photos: Roger Davies for “Outside In: The Houses and Gardens of Tichenor & Thorp.”

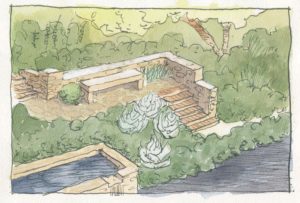

A watercolor rendering of the Rancho Santa Fe house by Tichenor.

Their projects include everything from remodeling a new home for three-time clients to the ever-expanding new campus for the Los Angeles Times — plus they’re creating soothing interiors for a cancer clinic, Chan Soon-Shiong.

Tichenor & Thorp Architects, the multi-disciplined Los Angeles, California, firm, has completed more than 350 projects worldwide. Originally known for their skilled, historically informed, but innovative restorations of landmark 20th-century houses around Los Angeles (a few better known for the film-world luminaries who lived in them than for their architects), they’ve gone on to design residences and commercial projects with a signature sensitivity to the sites.

Every window frames a painterly view of the gardens. Here, an outdoor dining area as seen from the guest house at Rancho Santa Fe.

A hallmark of California Modernism was the blurring of lines between indoors and outdoors. In the 21st century, that’s become a given, an absolutely essential feature of the architecture of the West. But Tichenor and Thorp take it one step further: Their work begins with the site — with the outdoors — and that goes far beyond choosing the ideal placement of the structure. In fact, they begin by imagining the landscaping, and that dictates the design, creating a unique harmony. It’s an aesthetic best summed up in the title of their new book Outside In, published by Vendome in September 2017.

Tichenor and Thorp met in 1983, during their first year of graduate school, and opened their firm in 1990. What’s remarkable is not so much the success of their marriage and their 30-year business partnership, but that they maintain the same rebel spirit that originally drew them to the University of California, Los Angeles (UCLA) graduate program.

At the time, each was weighing where to study, and the trend at graduate architectural programs was toward turning out clones of whatever famed architect was the school’s leading figure. Tichenor and Thorp chose UCLA because the program was led by Charles Moore, who was regarded as a bit of a renegade. He had a far more eclectic view of what constitutes good design, arguing for reinserting the human element into modernism and for returning architecture to more contextually and site-appropriate design. His practices were also multi-disciplinary.

The redesigned gardens retain some Le Nôtre-inspired formalism, but the lawn, now more like an outdoor carpet, is framed in colorful Mexican sage.

The redesigned gardens retain some Le Nôtre-inspired formalism, but the lawn, now more like an outdoor carpet, is framed in colorful Mexican sage.

The early 1980s were an exhilarating time to be a budding architect in California. The Southern California Institute of Architecture was in its infancy, the Richard Meier-designed Getty Center was just getting off the ground, and “There was a kind of funny us-against-the-world quality, a kind of can-do, wide-open craziness going on,” Tichenor says. “And that was why you came to Los Angeles. It was just a tumultuous, exciting time to be around.”

“Charles Moore’s point of view encompassed a lot of styles,” Thorp adds. “He was interested in history, but kind of twisting things on their heads. And the other thing about him was he had a great interest and aptitude for site design.”

“We [designed] tons of landscaping,” says Tichenor, who worked for Moore throughout graduate school — and for a couple of years after — then partnered with now-celebrated landscape architect, Nancy Goslee Power, designing more than 100 gardens across the world.

The entry’s black-and-white, tiled, limestone floor is flooded with light from French doors. An 18th-century panel hangson the far wall.

The entry’s black-and-white, tiled, limestone floor is flooded with light from French doors. An 18th-century panel hangson the far wall.

“We conceive of the process as a whole,” Thorp says of the firm’s philosophy, “and most architects will tell you that, but they design from the inside out. In other words, there’s some core thing, and then they work the idea out. We go the other way. It’s kind of like Marie Kondo saying she organizes. It seems obvious, but I don’t think it’s as obvious as it sounds. Most architects are not trained to do landscape design.”

A 1950s Picasso tapestry, based on his 1911 painting Le pigeon aux petit pois, hangs over an antique boiserie.

The guest bedroom, with its scroll bed and beamed ceiling, opens onto one of the last remaining lawns.

“I think we’re as concerned at the start of the project with what kind of trees will do well on the site as we are about what the rooms will be like,” Tichenor says. “Designing the ideal gardens has equal footing with where the great room will be; the symbiosis between what you’re seeing out the window and what you’re looking back at while walking in the garden.”

These days most of their projects are modern in design, but the couple is just as happy working in a traditional vernacular. Their ideal clients have collections of art or antiques, or are driven by some passion.

“What sparks you? That’s what really makes you snap to attention,” Tichenor says. “In the end, it’s taking the things a client’s really moved by and putting them together in a way that’s an expression of who they are.”

A major collection of post-war and contemporary California art and a Palm Springs lot with a dramatic clump of palms inspired a design that reverted the existing pattern of houses facing the street with backyards. Tichenor and Thorp set the house at the rear of the property and positioned the garden and pool, hidden from view by hedges, to enjoy the striking views of the San Jacinto Mountains that draw people to the area in the first place.

In an updated dining room, an 18th-century sideboard sits below a multi-panelled painting by Tichenor in ink, encaustic, and gold leaf.

In an updated dining room, an 18th-century sideboard sits below a multi-panelled painting by Tichenor in ink, encaustic, and gold leaf.

At initial meetings with clients, the architects show up armed with stacks of books for inspiration. Their endless, insatiable interests have amassed a library ranging somewhere between 6,000 and 8,000 architecture, art, and design books. These days, clients often have Pinterest boards as well.

“No matter how all over the map the board may be,” Thorp says, “we can see where it’s going. And we can often find other references, or the one page they’ve posted is from a 700-page, fabulous book they don’t even know exists. We like solving problems,” she says. “We don’t have a driving need to solve some core problem within ourselves by designing a signature building that’s going to be reproduced everywhere. A lot of people think of architecture as an art. It’s not. We’re a service industry.”

“Well, it’s art-like,” Tichenor suggests.

The powder room’s intriguing antiques include the base of the marble wash stand and antique ironwork from France.

An early rendering of the water terrace by Tichenor.

“We’re not making art,” Thorp insists. “We’re designing. Design solves a functional problem. And if that problem happens to be seven containers of antiques from France, bring it on.”

Those containers housed the collection belonging to homeowners, for whom Tichenor and Thorp, in the mid-90s, first designed a garden, then a French bastide-style house on a large site in Rancho Santa Fe, California. Recently, the homeowners were considering a new house (the original, as Thorp put it, had become a “little too Marie Antoinette”).They were encouraged to update instead. As before, Tichenor and Thorp started on the garden, which was a joy, because over the subsequent decades the trees had grown in as envisioned.

The stately water terrace by the pool, with a ribbon of Mexican sage in the background.

When it came time to update one room, Tichenor and Thorp were uncharacteristically uncompromising: “It needs to be pink.” They selected a tone from the pink sky of a Barbizon painting that was also the focus of the room. “They were scared,” Thorp says, laughing.

“It was even worse than that,” Tichenor adds. “It was: ‘Here’s a color that’s safe, and here’s one that’s not. If you really had any guts you’d go for this.’”

“But they’re very brave. They went for it,” Thorp says.

“Yes,” Tichenor says. “We stretch them and they stretch us.”

For decades, long before droughts made them ubiquitous, their gardens have been designed as dry, Mediterranean-inspired expanses with a minimum of water-sucking lawns. No beds of impatiens here, but plenty of color, from ribbons of lavender to spikes of giant Canary Island echium.

Tichenor majored in fine arts at the University of California, Santa Barbara. He was working on a master’s in architectural history when his professor, David Gebhard, the well-known author of books on California architecture, pulled him aside. “He told me I really should be an architect,” Tichenor says. “Something to the effect that I would make young people in Oklahoma miserable teaching them art.”

Flipping the quotidien backyard upside down, the hedge-hidden spa, pool, and cabana of this Palm Springs house faces the street to take advantage of the dramatic view of the San Jacinto Mountains.

Flipping the quotidien backyard upside down, the hedge-hidden spa, pool, and cabana of this Palm Springs house faces the street to take advantage of the dramatic view of the San Jacinto Mountains.

Contrasting with the contemporary art and clean, modern design, a copper tub sits below a mirror-framed fireplace and a 19th-century School of Paris painting.

The desert gardens are a blend of Mexican fan palms, Canary Island palms, and gray-green bitter aloe, splashed by the vivid coral bougainvillea.

Thorp took a class at Bryn Mawr taught by a Yale architecture student who created an architecture studio, but neglected to educate her students on the rudiments, which led to some comic misunderstandings: “Like learning how to use a T-square,” Thorp says. One student thought she knew how — but her idea was that the T-square hung from the top of the drafting board. “It was only later when I started to work for an architect that I found out the T-square went up and down on the side,” Thorp says, laughing.

Thorp’s senior thesis included a none-too-successful design of a student dormitory, but she’d been encouraged by a summer course at Harvard. She moved to New York, where she worked for an architectural firm for a couple of years before deciding to attend graduate school.

“It was good,” she says of the zigzag road she took. “It kind of rolled into a ball. It’s like acting — every experience you’ve ever had you can throw into the mix.”

Two wings extend from the center living room; the stone-floor kitchen and interior dining area occupy one. | Contrasting with the contemporary art and clean, modern design, a copper tub sits below a mirror-framed fireplace and a 19th-century School of Paris painting.

Two wings extend from the center living room; the stone-floor kitchen and interior dining area occupy one. | Contrasting with the contemporary art and clean, modern design, a copper tub sits below a mirror-framed fireplace and a 19th-century School of Paris painting.

Neither can remember what the firm’s first project was. It might have been remodeling a 1930s house in the Hollywood Hills for Stewart Copeland of The Police, or a Paul Williams house for the future president of Capitol Records (they later did a remodel of the iconic Capitol Records building, which resembles a giant stack of 45s).

The art collector clients wanted space for their remarkable collection of postwar California art. The hallway ends with “Interior with Painting” by Helen Lundberg, on the left is Kim McConnel’s Cara Dos Mil, with Mary Corse’s “Untitled” over the bookshelves.

Art, a stone floor, and handcrafted items soften the clean lines of the architecture.

“We’ve been kind of the same size from the beginning,” Tichenor says of the firm, which fluctuates around a staff of 30. “We got bigger and then realized we were just going to meetings all the time. We actually built the office so that we couldn’t add a ton of people.”

“Yeah,” Tichenor says, “but we all work with everyone, so it’s really an atelier kind of environment.”

Their West Los Angeles office is a striking example of their aesthetic. Modern, light-filled, and blending into the surrounding buildings. Thorp’s office on the second floor leads to a large, living room-like terrace lined with plants, while Tichenor’s office has views of a distant line of trees, with a succulent-lined terrace.

When asked how they envision the future, what they’d like is the time to be more hands-on and design some smaller projects, including a return to craft. That could include designing cabinets, furniture, hardware, or lighting.

“We’re at the point where I think we’re at the peak of our powers,” Tichenor says. “At this age and at this point in our career, we’re given opportunities that are just incredible. I could see doing more intimate work, and I look forward to doing more gardens.” In other words: maybe smaller, more intimate, but definitely more.

No Comments