08 Nov Crow’s Shadow Institute of the Arts

In the early 1980s, James Lavadour was painting landscapes in an empty schoolhouse. The building dated to the 1930s, but the Catholic Mission it belonged to had stood on the land that became the Umatilla Reservation for more than 150 years. Lavadour lived in the old stucco building, and for his studio, he used a classroom with paint peeling off the walls and views of the Blue Mountains out every window. He had no formal training, but Lavadour (Walla Walla) had the support of his family, his tribal community, and local artists, including sculptor Betty Feves, whose husband was the reservation doctor. “I hear you’re an artist,” she reportedly said to him when they met. “Show me your work.” And he did.

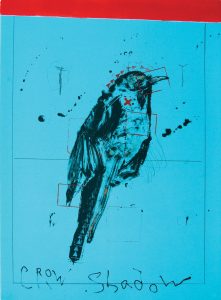

Rick Bartow (Wiyot), Crow Shadow Series | Monoprint, Series of 20 | 30 x 22 inches | 2013 | Collaborating Master Printer, Frank Janzen

Lavadour kept painting and, by the early 1990s, he had discovered printmaking and earned a fellowship at Rutgers University, where he studied under master printer Eileen Foti. In 1992, driven by the desire to support other artists with the kind of education and professional development he’d received at Rutgers and from his mentor Feves, Lavadour co-founded the Crow’s Shadow Institute of the Arts (CSIA) with Philip Cash Cash (Cayuse and Nez Perce), who had also used the old schoolhouse as a workspace for his printmaking.

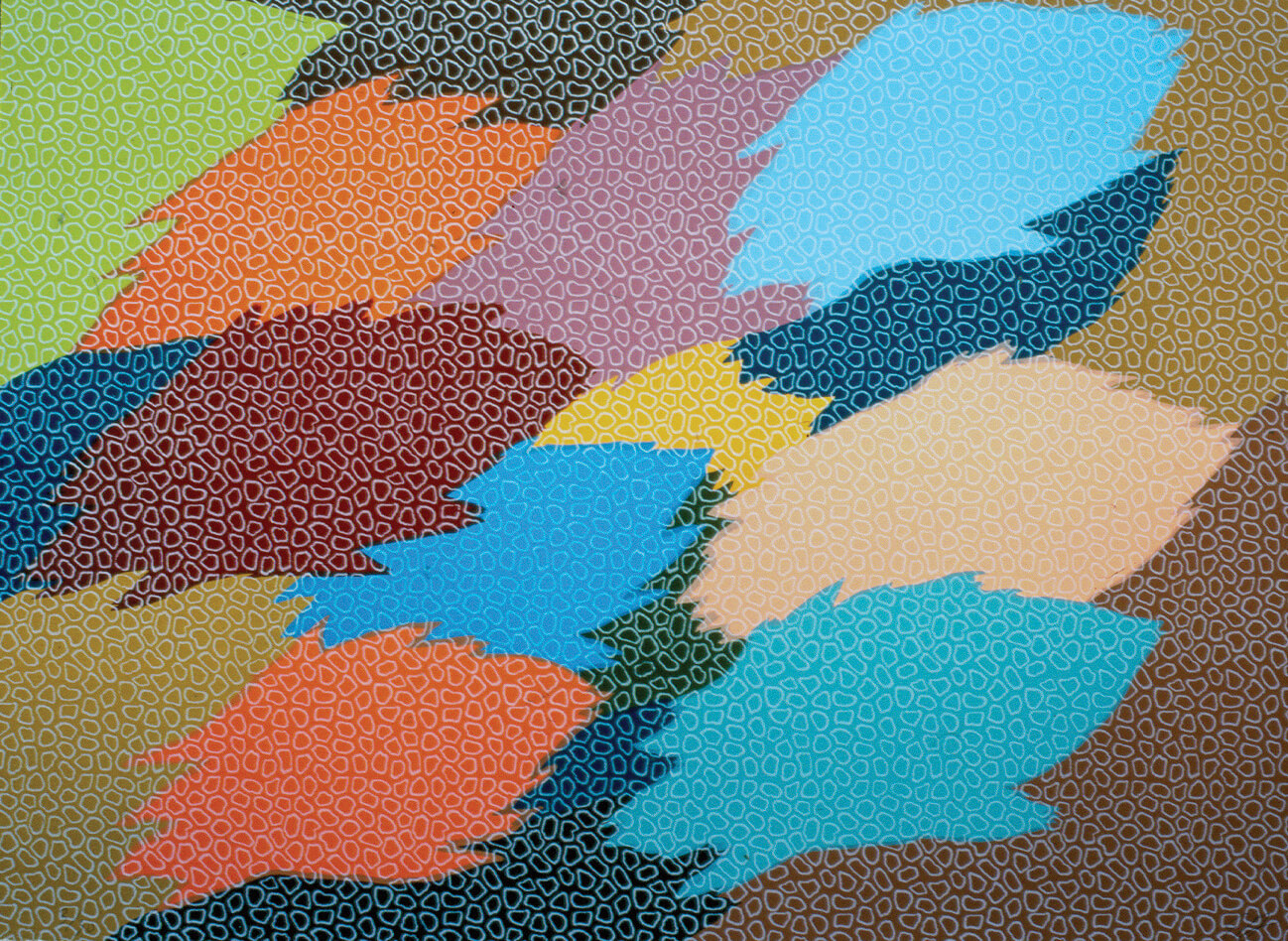

A studio space at the Crow’s Shadow Institute of the Arts. Photo Courtesy of CSIA

Within a year, Lavadour and Cash Cash had installed a Ray Trayle press in one of the classrooms, which they used to teach printmaking workshops. Then a USDA Rural Economic Development Fund grant allowed them to refurbish classrooms for gallery space, an administrative office, and a studio. In addition, they started a traditional arts program, where locals could study everything from beadwork and leathercraft to basket weaving and horse regalia. Crow’s Shadow Institute of the Arts was, and remains, the only professional print house on a Native American reservation.

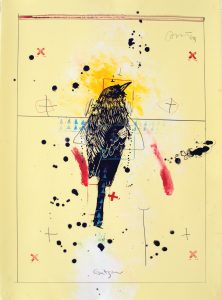

Rick Bartow (Wiyot), Gatsin Series | Monoprint, Series of 16 | 30 x 22 inches | 2013 | Collaborating Master Printer, Frank Janzen

In 2001, CSIA hired a master printer, Frank Janzen, and planned a week-long symposium called Conduit to the Main Stream. “They wanted to explore the idea of how Native art could fit into a wider contemporary arts community,” says Karl Davis, executive director of CSIA since 2014. Lavadour brought together 15 artists, scholars, and writers — including Kay WalkingStick (Cherokee), Truman Lowe (Ho-Chunk), James Luna (Payókawichum), Rick Bartow (Wiyot), Edgar Heap of Birds (Cheyenne and Arapaho), and Marie Watt (Seneca). Just out of graduate school, Watt recalls the profundity of the gathering. “There I was in the midst of people whose work I knew and had long admired. Oh my gosh,” she says.

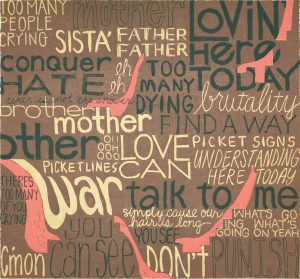

Marie Watt (Seneca), Companion Species (What’s Going On) | 4-color Woodcut, Edition of 14 | 17.5 x 18.5 inches | 2017 | Collaborating Master Printer, Frank Janzen

While the other attendees left the institute at the end of the symposium on September 10, 2001, mixed-media artist Heap of Birds planned to stay on a few more days to work with Janzen. Then came September 11th. Unable to travel, Heap of Birds stayed at Crow’s Shadow, and in just two weeks, while the world turned upside down, together he and Janzen created what would become a 30-print edition of an 18-color lithograph. “It was a massive project to take on for the first published print,” says Davis.

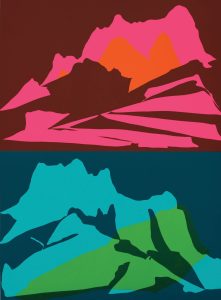

Kay WalkingStick (Cherokee), Wallowa Memory | 4-color Lithograph, Edition of 16 | 17 x 30 inches | 2003 | Collaborating Master Printer, Frank Janzen

Inspired by Janzen and Heap of Birds’ productive collaboration, two-week residencies became the mainstay of CSIA’s programming, says Davis. Each year, the institute invites three to six artists — mostly Native Americans and mostly from Oregon — to collaborate with CSIA’s master printer on a publishable series of lithographs, monoprints, or monotypes.

That collaboration, says Judith Baumann, who took over for Janzen as master printer in 2017, is what makes her job so fascinating. “Collaborating requires you to set your ego aside and focus on the artist you are working with,” she says. “You have to figure out how to translate their work.” CSIA invites artists from a wide breadth of genres — “artists of all stripes,” says Davis, including videographers, sculptors, textile artists, and even musicians — and many of the artists have no experience with fine art printmaking. “They don’t necessarily know what they are walking into,” Baumann says, so it’s her job to guide them with layering, color combinations, and more.

Founded in 1992, the Crow’s Shadow Institute of the Arts conducts two-week-long printmaking residencies from a Catholic Mission built in the 1930s on the Umatilla Reservation. Photo Courtesy of CSIA

“The opportunity to be a working artist and collaborate with a master printer is more than a gift of time and space,” says Watt. “They have extensive technical knowledge and areas of specialty they draw from to help the artist take their prints from concept to form. When you work with a master printer, it liberates your process and the way you make work.”

Watt, an interdisciplinary artist with a degree from the Institute of American Indian Arts and Master of Fine Arts in painting and printmaking from Yale, has completed five residencies at Crow’s Shadow. She jokes that she became the poster girl for CSIA after the 2001 symposium. Many of the people she met there became part of her artist community and the professional network that shaped her path forward. Similarly, working at Crow’s Shadow would become part of her artistic process. Watt talks about the drive to the old schoolhouse, along the Columbia River Gorge, and how her whole body settles as she gets closer. “It’s an extraordinary way to enter a place you are going to work creatively,” she says. “When I go to Crow’s Shadow, it’s another extension of a place that’s homelike to me. … The Blue Mountains, they call you.”

Artist Marie Watt (Seneca) works on a print at the Crow’s Shadow. Institute of the Arts in the fall of 2017. Photo Courtesy of CSIA

When the artists finish their work, all of which is original and made on-site in the old schoolhouse, CSIA keeps one print for its permanent collection, which is often loaned to museums and other cultural institutions. Since 2010, another print goes to the Hallie Ford Museum of Art in Salem, Oregon, which maintains a comprehensive and permanent archive of CSIA publications. All of the other prints from the series are available for sale to the public on the CSIA website, or at print fairs in New York City and Portland, Oregon, with the proceeds going back to the artist.

“Crow’s Shadow is a wonderful and unique organization that is actively trying to financially help the artists that come into the studio,” says Baumann. “And that can’t be said of other print houses. We try to get their work into homes that may have never heard of them.”

In addition to private buyers, many of the prints are purchased by major collections. Since Heap of Birds’ first print with Janzen, CSIA has placed prints in the Library of Congress, Museum of Fine Arts Boston, Portland Art Museum, Eiteljorg Museum, and the Whitney Museum of American Art, among others.

From his perspective, Davis says, the best part of printmaking is bringing the art to a broader audience. “One painting is one piece,” he says. “But an edition can be disseminated, allowing more people to see the artwork and learn about the artist. The more prints we make, the more people can experience art.”

Marie Watt (Seneca), Companion Species (What’s Going On) | 4-color Woodcut, Edition of 14 | 17.5 x 18.5 inches | 2017 | Collaborating Master Printer, Frank Janzen

Baumann sees advantages for collectors and artists alike. “Print is awesome because it allows people to collect artists’ work that they couldn’t otherwise afford … and it’s good for the artist. They have an edition of 15 to 20 sellable works of art in two weeks, which gives them the opportunity to net a decent amount of money and expand their collector base.”

Twenty years after 9/11 and nearly 30 years from the institute’s founding, Crow’s Shadow has never lost its way. The residencies are going strong, and the institute’s ties to the community through traditional art classes and workshops are robust. Davis talks about the challenges of Covid-19 and being unable to invite the public to see the work in person. But the silver lining, he says, has been generous donors who have helped the organization survive. “The fact that we’re still here is something,” he says.

Marie Watt (Seneca), Companion Species (Anthem) | 4-color Woodcut, Edition of 14 | 17.5 x 18.5 inches | 2017 | Collaborating Master Printer, Frank Janzen

Watt looks back on the 20 years she has spent in a relationship with CSIA and can’t help but feel hopeful. “This humble and world-class printmaking residency is now a coveted opportunity for artists. My sense is that the plans for the future are ambitious and visionary, to grow and stay true to its community-centered vision.”

No Comments