08 Nov In the Studio: Until We Meet Again

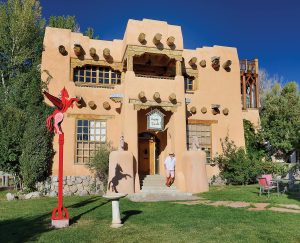

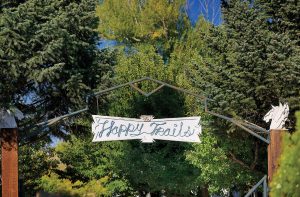

In an area of mostly single-story adobe houses in Taos, New Mexico, Thom “Tex” Wheeler’s home and studio is an architectural anomaly. Visitors drive through an arched entry gate with a weathered wooden sign declaring “Happy Trails,” and they are indeed about to embark on a journey.

Wheeler works on an enameled copper piece. Eventually, he’ll seal the work with marine varnish so that it can hang outdoors.

Once inside, guests are transported from the busyness of Taos to a park-like expanse of lawns filled with trees, flowers, and fountains. A courthouse-sized adobe structure sits opposite a Victorian building with stained-glass windows, creating an ambiance of a wonderland. “My home suits the whimsicalness I feel in my heart,” Wheeler says. In these spaces, he creates “art that springs from a joy of living.”

It took five years and about 38,000 bricks to create the adobe portion of Wheeler’s studio and home. The large vigas were harvested from nearby Wheeler Peak. A 16-foot-tall edition of Flying Stallion, painted and powder coated in a brilliant red, welcomes visitors.

If “happy” was an art genre, it would describe Wheeler’s work perfectly. His creative process draws attention to the moldable nature of metal: with textures made by etching, welded metal components fitted together like a collage, and added embellishments of colorful gems. Inspired by the jewelry designs of Native Americans in the Southwest, Wheeler creates “wall jewelry,” or wall-mounted sculptures with traditional Southwestern designs. And over the last 10 years, he’s created colorful enameled copper pieces, suitable to adorn indoor or outdoor spaces. One piece depicting a hummingbird contains malachite from Argentina, lapis from Afghanistan, and turquoise from the U.S. Southwest, an amalgamation that echoes the artist’s life experiences.

The entrance to the studio showcases many of Wheeler’s skills: cast concrete, welded steel, and stained glass.

When he was a Cub Scout, Wheeler knew he wanted to be an artist, but he doubted his ability to earn a living and instead pursued a business degree at Sam Houston University. During college, he also worked as a carpenter. Little did he know a chance encounter would change the course of his life forever.

In the studio, a collection of lights gathered from churches illuminates the space. A set of Dutch doors, one of 30 on the property, allows additional light to filter through.

Wheeler met art professor Charles Pebworth — who had gained a national reputation for his metal sculptures — to discuss the renovation of his studio. After seeing Wheeler’s artwork, Pebworth encouraged him to pursue a creative path.

Wheeler shapes a free-standing sculpture in the Victorian building, where work unsafe for walk-in visitors occurs.

Wheeler’s professional art career began in 1975 in Houston, Texas. He started working in wood and stone, combining the two materials into monumental pieces, ranging from 54-foot-tall bas relief wall hangings to 60-foot-tall sculptures. Many of these early works were commissioned, including a 45-foot long, 3-dimensional mural of an elephant family in the Serengeti that was installed in a restaurant.

One of Wheeler’s iconic designs, these crosses are adorned with turquoise in a traditional Southwestern style.

Wheeler’s love of travel and exposure to different cultures and art forms provided fodder for his creativity. While serving in the U.S. Army Medical Corps in Germany, he visited museums to study Renaissance artists. He found inspiration in American sculptor David Smith’s works and intrigue in Pablo Picasso’s paintings, and all of these influences became muses for his work. Wheeler moved to Taos in 1985, and the landscape and heritage of the area influenced the direction of his art. He began interpreting the icons and lore of the cultures around him.

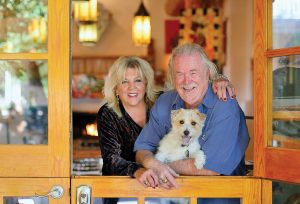

Wheeler warmly welcomes visitors to the studio, and his wife, Lavinia, and their four-legged friends, Shellie and Scout, are there to help.

A pirate inspired this work-in-progress; Eagle Eye includes an eye with a cross and sports a gold earring.

Stained-glass windows are a part of each building on the property. In the adobe studio, colorful light radiates through a set of stained-glass windows on the north wall. “Those came from a Presbyterian church in Mexia, Texas,” Wheeler explains. “I bought them because of the wonderful light they create.”

This accessory box was created from parts of an 1889 Singer sewing machine. The finished piece will form a square to display the lapis-filled bears.

Ninety percent of the metalwork is created in this studio, while the other 10 percent is done in the Victorian building, the artist explains. “I call that 10 percent my dirty work. The building started out as a horse barn but got fancied up,” he says.

Remnant copper pieces become abstract art when light streams through a stained-glass window.

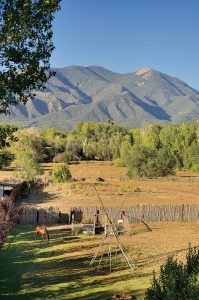

When in 1985 Wheeler started building on his 2-acre property in the small New Mexican town that had attracted many great artists over the years, the process began as other adobe structures had for hundreds of years, with the artist gathering materials. “With the help of the Forest Service, I was able to harvest huge logs called vigas that would be the support for ceilings of the studio,” Wheeler says. “Mules were needed to harvest them from the rugged terrain of Wheeler Peak.” At an elevation of more than 13,000 feet, it is New Mexico’s highest point and the tallest of the Sangre de Cristo Mountains on the southern end of the Rockies. “Once the logs were brought down off the mountain, I had to take them through a car wash to rid them of caked mud and grime before they could be stripped of their bark,” he says.

Wheeler’s Flying Stallion series ranges in height from 8 to 20 feet tall. A favorite icon, the artist says they’re more than just horses to him. “Somehow, being winged adds a spiritual feel,” he says.

Adobe bricks — 38,000 of them to be exact — were required to build the 5,500-square-foot structure. The studio walls reach 36-feet high to meet the grandness of the elevated ceiling; the huge vigas extend through the exterior walls, serving as an architectural element on the outside. “I overdo everything to my liking. I like massive walls,” Wheeler says. “It’s the only way I know how to do it. I’m on a thousand-year plan, I build everything super strong so it will last forever.”

Wheeler created his studio and home to act as an artistic haven, with carefully curated indoor and outdoor spaces.

Upstairs, above the studio, a living room, dining room, and kitchen share an open floor plan. On a clear day, the western views from the second story include Pedernal, the peak that Georgia O’Keeffe made famous, while to the east, one can watch the sun rising over Taos Mountain. Not content with the large deck on this second story, Wheeler added another stairway to a crow’s nest where at night “the Milky Way seems as if you can reach out and touch it.”

Mountain views, including Wheeler Peak (right), are visible from the crow’s nest atop the adobe studio.

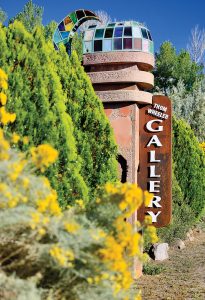

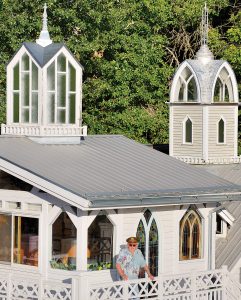

In addition to containing more workspace, the Victorian building also includes guest quarters that Wheeler built for his parents. The fairy-tale-like structure is topped with turrets and birdhouses. “I love birds,” he says. “That’s why I built them a home, too.”

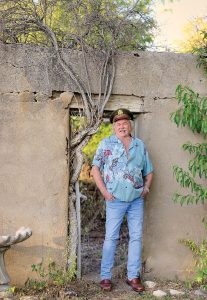

Wheeler stands at the entrance to an 1840 ruin, abandoned over 100 years ago

A storybook property, it has many tales to tell — stories of garden parties and fundraisers and birthday parties, including one for glass artist Dale Chihuly, who filled Wheeler’s pond with colorful glass globes. The bigger story is that from this Northern New Mexico town, Wheeler’s art has found homes around the world, from collectors such as Jonas Salk and Randy Travis to the Banco di Roma in Italy and the University of Mississippi.

The artist constructed a 15-foot-high waterfall that pours into a pond. The exposed stone in concrete is reminiscent of Frank Lloyd Wright’s structures. “I’ve spent a lot of time at his homes, studying how he worked his stone. This is an example of his ‘slip stone’ way of using natural rock,” Wheeler says.

Leaving Wheeler’s wonderland, the verse of “Happy Trails” has a perfect message for any and all visitors… Happy trails to you, until we meet again.

Wheeler designed the Victorian building to include cupolas with antique weather vanes and lightning rods, similar to his childhood home in Galveston, Texas.

Wheeler and his wife, Lavinia, welcome visitors to the studio along with Scout, their Jack Russell terrier, who is often referred to as “Boss.”

Wheeler’s “Happy Trails” sign is made of painted rope. On the right side of the gate is the head of a stallion he created in 1982.

No Comments