08 Nov Perspective: A Star on the Rise

Friends called her Beck or Becky. She dressed in traditional Western garb — denim breeches, boots, and kerchiefs — and topped her mane of prematurely silver hair with felt hats. An ever-present cigarette dangled from her lips. Her face, sometimes embellished with bright red lipstick, was full of gravitas, strength, and stories. She was boisterous, a down-to-earth whisky drinker who rode a wild little horse.

Peter Stackpole, El Crepusculo – Taos | Gelatin Silver Print | 9 x 6.5 inches | Date Unknown | Collection of the New Mexico Museum of Art

On the surface, Rebecca Salsbury James’ raw, free-spirited image seems incongruous with the almost ethereal, refined, detail-oriented, and intimate quality of her art. Yet, her reverse glass paintings and colcha embroidery were expressions of her deepest self, and the earnest intention behind their creation remains palpable. This self-taught artist made a lasting impact on Modernism by following her inner impulses and rendering the beauty she saw in simple things and folk traditions.

James didn’t let concepts of high art or low art limit her creative spirit, explains Christian Waguespack, the curator of 20th-century art at the New Mexico Museum of Art. Waguespack appreciates the fact that she didn’t “shrink from the difficulty of learning and mastering very difficult techniques like colcha and reverse glass painting, which are both seriously challenging media to work with.”

James was born in London in 1891, the daughter of American parents who were traveling with Buffalo Bill Cody’s Wild West Show, which her father co-managed. Though they returned to the U.S. and settled in New York City when James was young, her sensibility remained rooted in a vision of the American West that was celebrated in Cody’s show, and she was greatly influenced by formative years spent among the likes of such larger-than-life figures as Annie Oakley and Sitting Bull.

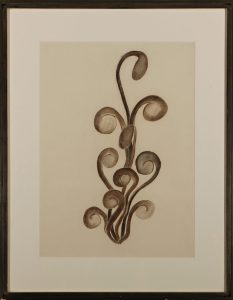

Bean Sprouts | Charcoal and Wash on Paper | 18.25 x 6.8125 inches | 1934 | Collection of the New Mexico Museum of Art. Gift of John Robertshaw III, 2014 (2014.7.7).

As a young woman in New York City, she found a different, equally vibrant tribe: the visual artists associated with visionary photographer Alfred Stieglitz. In 1922, James’ husband, photographer Paul Strand, introduced her to Stieglitz and his circle. James had graduated valedictorian from her teaching college and was working as a secretary, and the community of artists lent a whole new dimension to her life. She dabbled in painting, drawing, and photography, but she wasn’t satisfied with her work and yearned to develop. During this period, she felt most creatively fulfilled while posing for Stieglitz, who immortalized her in an array of luminous nudes. But it was her connection to Stieglitz’s wife, Georgia O’Keeffe, that might have made the greatest impact on James.

James loved and looked up to O’Keeffe like a big sister, emulating the latter artist’s style of dress and her penchant for painting in the buff. O’Keeffe’s burgeoning success as a painter inspired James to find her own voice as an artist. When O’Keeffe curated a 1928 show at New York’s Opportunity Gallery, she included pastels of fruit and flowers by James, giving the younger artist her public debut.

James’ impact on O’Keeffe was no less significant: She’s the one who brought O’Keeffe to New Mexico, introducing her friend to the landscape that would inform and inspire her iconic work for the rest of her life. This happened in 1929, when the two women left their husbands behind in New York and spent a summer painting in Taos. While O’Keeffe was “driven by her excitement for land and place,” Waguespack notes, “James was driven by her enthusiasm for practice and material.” During that seminal season, James moved away from her pastels and began reverse painting on glass.

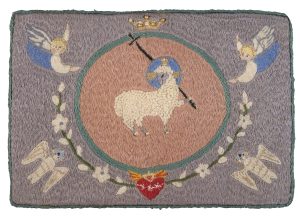

Agnus Dei | Colcha Embroidery | 7.25 x 10.5 inches | Date Unknown | Collection of the New Mexico Museum of Art. Museum Purchase, 1998 (1998.35.1). Photo by Blair Clark

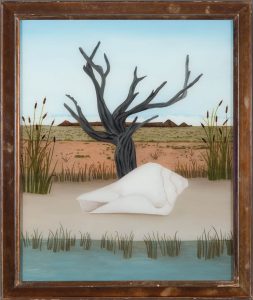

With roots in folk art, industrial sign making, and devotional art — including innumerable religious icons — reverse painting on glass was far from avant-garde when James began doing it. The tricky process requires that an artist work backward. First, James would paint her subject’s details and highlights, then the background. Once she finished painting, she turned the piece over. Viewed through glass, her paintings have a glow that’s felt in the heart — a moving quality of depth and luminosity, as well as of distance and untouchability.

Flowers, shells, trees — all portrayed with pleasing, at times slightly surrealist simplicity — seem to breathe behind the glass of James’ paintings. The green leaves in White Hollyhocks look alive, full of movement and juice. In Brown Bear’s Tooth and Honey Locust Thorn, James zooms in on these small natural phenomena, giving them the stature of a leafless tree and a crescent moon. She painted the camposantos of New Mexico with their weathered crosses, as well as grasses, mountains, smooth adobe houses, curvaceous ceramic pitchers, and vegetables. She had a special fondness for the artificial white roses placed in churches as a tribute to the Madonna.

Earth and Water | Reverse Oil on Glass | 19.75 x 16 inches | 1950 | Collection of the New Mexico Museum of Art. Bequest of Helen Miller Jones, 1986 (1986.137.11). Photo by Blair Clark

James’ sensitivity to the humble, everyday objects of her environment shines through the glass. Several of her works feature a woman walking alone through the desert landscape that inspired her. “These [Taos] scenes made me a painter, and I am grateful,” she said. “A walking woman, a waiting woman, a watching woman, a mourning woman, a devout woman, adobe, cedar posts, old dry wood, the fields of alfalfa, the churches — I love these things. They have made me paint, and I am grateful.”

James permanently settled in New Mexico in 1933, having amicably divorced Strand and married William James, who ran the Kit Carson Trading Post. Her deep connection to the place and its people catalyzed her interest in the other art form that captivated her: colcha embroidery, a style of needlework with roots in colonial New Mexico.

Like reverse glass painting, colcha embroidery is part of the folk tradition, and it demands both technical skill and patience. After learning about it while taking Spanish lessons from her neighbor, Jesusita Acosta Perrault, James dove into the practice, viewing it as a form of meditation as well as art. Working one stitch at a time with yarn made from sheep’s wool, she embroidered traditional colcha subjects, including flowers, birds, and other natural phenomena, on a background of woolen fabric. Perhaps the highly-textured creations were a satisfying contrast to the smoothness of her reverse glass paintings. “This versatile stitch, for me, has provided a creative means to make a statement with stitches,” James said. “The living world around one — the skies, the land, the people, grasses, trees — can be imbued with immediate life…” Like many of her paintings, James’ embroideries feature botanical elements, as well as landscapes, birds, and the Catholic religious imagery that surrounded her.

“One of her most important contributions to the world of modern Western art,” Waguespack says, “is the way [her work] served as a bridge between local artistic traditions and national discourses in Mwodernism. Her interest in colcha in many ways revived the practice in Northern New Mexico, since she not only practiced it herself but hosted community stitching events to revive interest.”

Watching Woman | Oil on Glass | 18 x 21 inches | Date Unknown | Collection of the New Mexico Museum of Art. Bequest of the Rebecca Salsbury James Estate, 1968 (2298.23P).

By the 1950s, James began earning increased recognition and respect for her uniquely unpretentious yet affecting art. These days, contemporary viewers can still feel the unique spirit behind the work. “Art lovers are unusually excited to see her work and learn more about her life,” says Waguespack, “and they’re often surprised that she is not more well known.” Indeed, James still has a somewhat undiscovered quality. During her lifetime, various factors contributed to this, including the struggle to be taken seriously as a female artist in the early 20th century; her somewhat inconsistent practice; her status as a “sidekick” to more famous Modern art luminaries; and her work’s vulnerability to such dismissive labels as “decorative,” “domestic,” or mere “craft.”

Despite these challenges, her career included 12 national exhibitions from the late 1920s to the mid-1960s, as well as annual exhibitions at the New Mexico Museum of Art in Santa Fe and the Harwood Museum of Art in Taos. Toward the end of her life, James estimated that she had made 200 paintings and an equal number of embroideries. She wasn’t much for self-promotion, however, and gave a huge quantity of her art away to friends. Since her death in 1968, these gifted works have gradually found their way into museums where more viewers can connect with James through her refreshingly pure and technique-driven art — a “fresh aesthetic in the realm of Southwest Modernism,” Waguespack notes, “that people are happy to discover.”

No Comments