05 Nov Transcending Still Life

On the second day of working on a still life painting not long ago, Sherrie McGraw found herself in a familiar and frustrating situation. The first day, propelled by a strong sense of the visual idea she wanted to convey, the painting had gone well, and she was excited about it. But on the second day, something went awry. She wiped it down and started again. Her husband, painter David A Leffel, had also been delighted by her previous day’s work. Standing by her easel as she began again, he said, “Sherrie, you’ve got a tiger by the tail.”

Copper and Roses | Oil on Board | 9 x 11.5 inches | 2020

It was exactly what she needed to hear. Suddenly she understood why her work often began well and then seemed to flounder. She realized that although she started supercharged by inspiration, she tended to veer away from her initial idea, unaware that she was doing so. “It was a revelation,” she says of the insight sparked by her husband’s comment. “It made me realize I had the idea for this painting, and it was a good one, and this time I was able to paint the idea all the way through from beginning to end. It’s one of the best paintings I’ve ever done.”

Holding firmly to the “tiger’s tail” of creative energy, McGraw produced The Playthings of Time. The painting features a Chinese Tang Dynasty horse statue along with an upside-down, ancient ceramic bowl, a scattering of rose petals, and a miniature dark clay vessel. The dynamism of light, shadows, and texture creates a magical, almost-Pegasus-like feeling of excitement in contrast with the horse’s unheroic, ordinary pose.

The Playthings of Time | Oil on Board | 30 x 28 inches | 2017

For McGraw, it’s the abstract qualities of a representational painting that give it life: shadows and light on objects, value relationships, the way brushstrokes move, and how colors seem to change according to what’s around them. Viewers respond to these elements, often without knowing what keeps them lingering in front of a piece. But an artist needs to know.

“What’s often done — and why a lot of Realism gets a bad rap — is trying to simply replicate what the painter is seeing,” she says. “The work that I respond to and that’s haunting and visually stimulating is because the artist understood something different about paint, value, color, and light — all these abstract things that make up a painting.”

McGraw is sitting in her studio at the house she shares with Leffel near Taos, New Mexico, where they settled in 1992. It’s a chiaroscuro space with tall, dusky-colored walls and high, angled, north-facing windows, ideal for controlling light and shadow on arrangements and portraits. Large panels hold figure drawings from the weekly life-drawing sessions McGraw leads. On shelves along the walls are more Tang horses, old ceramic or glass vessels, venerable objects in brass or wood, and multiple vases filled with dried plants and flowers from the artists’ extensive gardens.

Duck Effigy Vessel with Delphinium | Oil on Board | 9.5 x 14 inches | 2021

The things McGraw loves to paint are the same kinds of things she loved playing with as a girl: small dishes she made from mud, miniature grass houses, berries, flowers, twigs. Her world today is focused on the visual, just as it was when she was a child. Growing up in Ponca City, Oklahoma, she remembers rarely talking, although she laughed a lot. And she drew. At various points in her childhood, this included drawings of plaster cast replicas of sculptures by famous artists that her mother had acquired and copying drawings by Italian masters. “It was my complete pleasure to sit for hours and draw. It was just like eating ice cream; it was so much fun,” she says. By age 4, she knew she wanted to be an artist.

Her other favorite activity was observing and listening to the people in her life. She remembers, also at age 4, accompanying her mother on a visit to a friend’s house. While the two women drank coffee, played bridge, and chatted, McGraw sat and took it all in, perceiving deeply through their voices and gestures as much as through words. She realized her mother had given up big dreams, perhaps of being an actress or writer, to be a mother of seven. She could see her mother’s artistic sensibility in the midst of a non-art-focused, provincial life.

McGraw was determined not to lose her dreams, so she decided to be as unlike her mother as possible: she would not drink coffee, play bridge, learn to knit, get married, or have kids. Aside from marriage, McGraw stuck with all of those vows. But more importantly, she never diverged from a visual way of being in the world. She was always intensely observing, and this became a cornerstone of her relationship with art. From her father, a golf pro, she gained a strong work ethic and the gift of being fully encouraged to do what makes her happy.

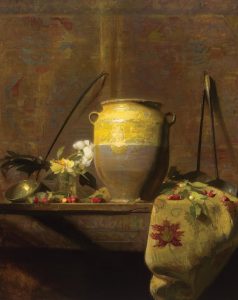

Nature, The Mistress of Art | Oil on Board | 32 x 27 inches | 2021

Following high school, McGraw studied with Richard and Edith Goetz at the Goetz Art School in Oklahoma City. At the end of three years, the couple encouraged her to move to New York City to study at the Art Students League with either Leffel or his teacher, Frank Mason. McGraw signed up for Leffel’s classes — a life-changing decision. She immediately perceived that his understanding of painting was entirely from first-hand experiences rather than simply passing on other artists’ tips. “With David, there was a complete shift in how I saw painting. He brought it all together — it was simple, logical, holistic, and made sense,” she says.

Early in her career, McGraw began earning honors and awards, and three stand out as especially meaningful to her: In 2010, she was awarded an honorary doctorate from the Academy of Art University in San Francisco; in 2014, the Butler Institute of American Art in Youngstown, Ohio, presented a solo retrospective of her works; and in 2015, the Butler chose McGraw for a Medal of Honor for Lifetime Achievement in American Art. She’s also served as vice president of American Women Artists and is the author of the book The Language of Drawing: From an Artist’s Viewpoint. Currently, her work is part of the Woolaroc Retrospective Exhibit & Sale at the Woolaroc Museum and Wildlife Preserve in Osage County, Oklahoma, through December 31.

Remains of the Day | Watercolor | 28 x 20 inches | 2020

John Pence, owner of the John Pence Gallery in San Francisco, represented McGraw for eight years before retiring in 2017, after 42 years in the art business. At age 85, he considers his relationship with both McGraw and Leffel among the most important influences in his understanding of art. He notes how examining one of McGraw’s paintings reveals countless tiny, beautiful abstract “paintings” that emerge through her brushstrokes. While she paints what she sees, he says, “it’s the result of a huge amount of dedicated looking.” Pence also points to a special quality of the artist’s brushstrokes that results in part from mixing oils with a thinning medium now called Maroger, known for its use by the Old Masters. “Titian and Rembrandt understood it, but it’s not easy to work with,” he says. Of McGraw as a painter and a person, he declares: “She’s a marvel.”

Just as Leffel’s masterful teaching had an enormous impact on McGraw’s art, she has influenced countless drawing and painting students over the years. By age 30, she was teaching at the Art Students League in New York City and has continued with private classes and workshops around the country. In the mid-1980s, she and Leffel began teaching together. A current collaborative effort is a weekly live stream with McGraw behind the camera and Leffel — who recently turned 90 — talking about art online at Bright Light Fine Art.

Steven Haas, a contemporary photographer and art historian in New York City, studied drawing with McGraw in the late 1980s. He credits her with opening his eyes to the process of making art. Haas remembers McGraw sitting beside him during a class, looking at his drawing, and gently asking what was troubling him. Startled, he asked how she knew something was wrong. “I can see it in your lines,” she said. At that moment, he understood that making art is a process of self-revelation. It’s about putting one’s inner state of being — one’s feelings and perceptions — down on paper. “That was a major breakthrough and one of the most extraordinary gifts I’ve ever been given,” Haas says.

The Emerald Moccasins | Oil on Board | 17 x 26 inches | 2021

For McGraw, bringing all of herself into the artistic process creates a direct and constantly changing relationship with her subjects. It’s why she never works from photographs, and it’s how she achieves a transcendental quality of aliveness in her work. “The light is shifting, the flowers are drooping, the leaves are changing,” she says. “All the things that make it harder to paint from life are what make it interesting. That’s the beauty of it, that incredible dance of dealing with life on the move.”

No Comments