07 Nov Art as Advocacy

Adrian Aguirre grew up with a foot in two worlds. Born and raised in Ciudad Juárez, Mexico, just south of El Paso, Texas, he crossed the border between the cities twice every day: to attend his American school in the morning, and to return home in the afternoon.

The artist’s work similarly inhabits two realms: art for art’s sake, and art with a purpose. His works are so stunningly realistic, skillfully rendered, and arrestingly expressive that they can easily please viewers who may value them as objects of aesthetic interest. But Aguirre’s work is intentional — art with a political agenda as he puts it. Through painting, he strives to humanize migrant workers, refugees, and immigrants, fostering greater compassion for those whose lives are shaped, constrained, destroyed, or otherwise defined by borders and the longing to cross them.

Gisele | Oil on Canvas | 36 x 36 inches | 2020

While Aguirre’s formative years had positive elements — “I had the opportunity to have friends on both sides, learn two languages, and love two cultures” — he also witnessed hardships. “Over the years, I saw how my parents seemed powerless when challenged by border officials. While most [officials] were polite and respectful, it was clear that there was nothing we could do when they were not. I know how difficult it is to immigrate. Immigration policy favors the wealthy and can be cruel and unjust towards those who aren’t.”

Certain childhood moments shaped the sensibility Aguirre would evince as an adult artist. “One of my earliest memories about the border,” he says, “was when my family camped on the Bridge of the Americas in El Paso/Juárez to line up to apply for a border crossing card the following morning. I remember being amazed to see so many people — there must have been hundreds — sleeping on the side of the street.” It was an indelible real-life image, and his paintings are now populated by real people who have crossed or are waiting to cross a line.

Campo Barretal | Gouache and Graphite on Paper | 12 x 10 inches | 2019

Opening on January 24, the Strata Gallery in Santa Fe, New Mexico, will host a show of Aguirre’s work through February 4, 2023, with an opening reception on January 27 from 5 to 7 p.m. During his exhibitions, viewers are struck by the emotive, familiar quality of the individuals who live in Aguirre’s portraits. “Many have told me that they can feel the expression, or that the person reminds them of a friend or a family member,” the artist says.

Painting is a meaningful outlet for Aguirre’s lifelong creativity, which manifested as a love for drawing in boyhood and led him to earn a Master of Fine Arts in painting from the University of North Texas. For his thesis, he completed Jornaleros, a series of paintings and drawings of day laborers — most of them migrant workers — in Denton, Texas.

José | Oil on Canvas | 28 x 22 inches | 2022

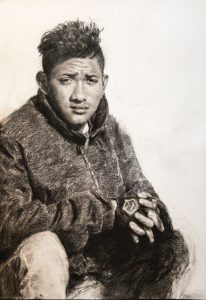

In portraying these men who gathered daily at the same site, each one hoping for a job, Aguirre’s process began before putting brush to canvas. He spent time sitting and talking with them and making sketches. The respect and empathy he felt for his subjects shines through the work. Several of the paintings are titled with the first names of the men they depict — Luis, Ricardo, Bermudez, Chente, Carlos, and Felipe — emphasizing that the faces, hands, jeans, and work boots in these portraits belong to living, breathing people with complex histories, dreams, and struggles. His subjects make direct eye contact with the viewer, and many of them hold up a piece of unmarked paper. Purposefully empty, the paper might read as a metaphor for the lack of legal documentation, but Aguirre conveys the beating hearts behind the blank sheets.

“I hope to elicit an emotional response,” he says. This is equally true of the series Migrantes. It is mainly comprised of portraits of refugees Aguirre encountered at “El Barretal,” a shuttered Tijuana nightclub that was used as a temporary camp for Central American migrants waiting to start new lives in the U.S. and Mexico.

Joven, Barretal | Charcoal on Paper | 30 x 22 inches | 2021

While much has been written about the inhumane conditions of such refugee camps, Aguirre chose to zoom in on the humans themselves. “I tried to bring out their personality and humanity, hoping the viewer will empathize and relate,” he says. As with the migrant workers, Aguirre’s process involved sitting among the refugees and sketching them. “Then if people seemed interested, they would ask me to draw their portrait. This broke the ice, and some of them would tell me stories.”

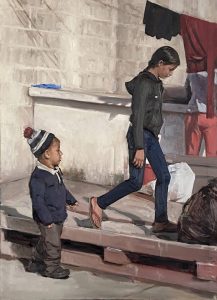

Lavabos El Barretal | Oil on Canvas | 48 x 34 inches | 2020

In Marta, the subject’s lined face is simultaneously infused with wariness, tenderness, expectancy, and resignation. She’s an older woman who has seen and felt much, yet retains a quality of softness. “She was very kind,” Aguirre recalls. “She shared with me that she had lived in California for many years but had been deported. She seemed not to be bitter about that.”

Lavabos El Barretal depicts two young people: a girl who looks a bit burdened, deep in thought; and a little boy who appears to want to engage with her. Behind them, a third person stands washing clothes. It’s a slice of life imbued with texture, light, shadow, and loneliness. “The young girl passed by,” Aguirre recalls, “but it seemed, at least for a moment, that the boy wanted to talk or interact with her.” Instead, each figure remains disconnected from the others.

Patwouy Cheval | Oil on Canvas | 22 x 28 inches | 2022

In contrast, Campo Barretal depicts a moment of connection and joy. “I saw the young men play soccer in the middle of the refugee camp. They had fun and laughed while playing.” And in Gisele, a charismatic young woman’s intelligent gaze, tilted head, and grin convey the strength of a good-natured spirit in less-than-ideal circumstances.

In his most recent series, Patrol, Aguirre, who now lives and works in Las Cruces, New Mexico, shifts his focus from migrants to the figures with whom they unwittingly find themselves at odds: border patrol officers. These works were inspired by photos Aguirre saw of Texas border patrol agents and the Haitian immigrants they pursued on horseback. Each painting is titled in Haitian French and captures moments of confrontation between the powerful and the powerless. The dark sunglasses and straight mouth of the agent in Patwouy Cheval serve to intimidate; seen from behind, the upraised arms of a migrant confronted by an agent’s horse in Travése Rivye A seem to supplicate.

Marta | Charcoal on Paper | 42 x 30 inches | 2019

In deciding what to paint, Aguirre says, “I look for narratives, how the figures relate to each other, gestures, and facial expressions.” He works primarily with charcoal and oil because he likes “how forgiving these two media are. I can make marks and erase them.” His work is characterized in part by the loose, expressive marks he employs to create movement and energy. “When I want to add a bit of color to a charcoal drawing, I’ll use gouache; and when I want more subtle tones, I’ll use graphite.”

Regardless of media, for empathetic viewers, Aguirre’s works capture the humanity of his subjects and the universal, relatable longing for a better life. His connections with his subjects are brief, but as multitudes of viewers experience the paintings, their impact can’t be measured.

Niños Jugando | Gouache and Charcoal on Paper | 30 x 22 inches | 2020

“I haven’t kept in contact with them,” he says of the people who inhabit his art, “though I would like for them to see it.” It seems unlikely, but one never knows. Perhaps Marta, Luis, Gisele, and some of the others will cross paths with their former selves — rendered in oil or charcoal — and view them from a perspective, one hopes, of greater security, safety, and prosperity.

No Comments