04 Jan Collector’s Eye: In silvertone and sepia

The well-known photographer Edward S. Curtis [1868–1952] was prolific during the early 20th century when cameras and film development were still in their budding stages. Between 1900 and 1930, he traveled the West, living alongside and taking portraits of people belonging to more than 80 Native American Nations from Alaska to New Mexico. His work culminated in the 20-volume book The North American Indian, which also presented the daily activities, customs, and religions of a people that Curtis feared were disappearing. Producing one of the most extensive photo collections in history, Curtis staged many of the photos to make them look like they were from an earlier time, as most Native Americans tribes had been relocated to reservations some 100 years ago.

“The great changes in practically every phase of the Indian’s life that have taken place, especially within recent years, have been such that had the time for collecting much of the material been delayed, it would have been lost forever,” Curtis wrote in the introduction to The North American Indian. “The passing of every old man or woman means the passing of some tradition, some knowledge of sacred rites possessed by no other; consequently the information that is to be gathered, for the benefit of future generations, respecting the mode of life of one of the great races of mankind, must be collected at once or the opportunity will be lost for all time.”

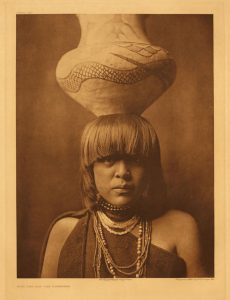

Edward Curtis, Girl with Jar — San Ildefonso | Photogravure | 16.625 x 12.25 inches | 1905 | Published in The North American Indian, Volume XVII, by Edward Curtis

Robb and Susan Hough of St. Petersburg, Florida, fell in love with Curtis’ work and amassed one of the largest collections in the country. “We so admire what he was able to accomplish using a giant box camera carried by horses and bringing glass negatives back to his studio,” says Robb. “It was quite the artistic achievement, as he experimented with a variety of printing techniques including platinum prints, gold tones, cyanotypes, and photogravures.”

In 2023, The James Museum of Western & Wildlife Art in St. Petersburg displayed photos from the Houghs’ collection along with Native American art, including pottery, baskets, carvings, and textiles, in The Stories They Tell: Indigenous Art and the Photography of Edward S. Curtis.

WA&A: What inspires you to collect art?

Susan Hough: Even before we started collecting Edward Curtis photos, we loved all different kinds of art, including paintings and glass sculptures. We enjoy getting to know the people who produce the art and learning about their backgrounds and stories.

WA&A: How did you acquire your Edward Curtis collection?

Robb Hough: It all started when I was skiing in Aspen about 16 years ago. A friend brought me to an art gallery, and I was blown away by an Edward Curtis photo of Native American teepees. Several years later, I brought my whole family and asked if they thought this was something we should invest in.

I’m not sure if he found us or we found him, but the late Christopher Cardozo was also instrumental in helping us acquire our collection, and a very large portion was previously owned by him. With a degree in photography and film from the University of Minnesota, Cardozo traveled throughout the wilds of Mexico, photographing Indigenous people. When a friend pointed out his work was very similar to Curtis’, he studied, acquired, replicated, and exhibited Curtis’ work for the next 50 years and became the foremost authority on him through his company, Cardozo Fine Art. We acquired approximately 723 portfolio photogravure prints, 1,100 smaller volume photogravures, and 200 masterworks, and are in the process of donating most of this material to The James Museum over a period of years.

WA&A: What is your most beloved photo and why?

R.H.: One of my favorites is Geronimo at age 76, taken the day before Teddy Roosevelt’s inauguration. Geronimo is dressed in what I understand was his war gear and he looks very intense.

I also love one of Middle Gun in goldtone printing-out -paper that is not published anywhere else, as well as a Hopi Walpi Man that is just gorgeous. The Hopis had a tradition called the Snake Dance, and they did not let people who were not of their culture participate or see the rituals. Curtis visited them every year for 10 years, so they grew to trust him and let him film and participate in the dance and related ceremonies.

S.H.: I love the photo of Slow Bull, an esteemed Oglala subchief and warrior who fought valiantly in numerous battles alongside other tribes.

I also appreciate several photos of young warriors that show so much emotion in their faces and eyes, making the photos intriguing and powerful.

Curtis also took many great pictures of Hopi women and other women, more than you would see from other photographers at the time.

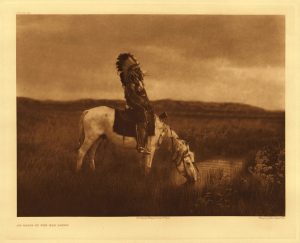

Edward Curtis, An Oasis in the Badlands | Platinum Print | 5.813 x 7.813 inches | 1905 | Published in The North American Indian, Volume III, by Edward Curtis, 1904–1908

WA&A: What inspired you to share your collection with The James Museum of Western & Wildlife Art?

R.H.: When my dad started his investment firm in St. Petersburg, Florida, William R. Hough & Co., the museum’s founder, Tom James, joined his dad’s company, Raymond James Financial. Dad and Tom were good friends who were very philanthropic and did a lot together for the local community, and Tom and Mary James decided to use their extensive collection of Western art to create The James Museum in downtown St. Petersburg.

We wanted our collection to be seen by the public and to remain in St. Petersburg, and we felt it was a perfect fit. We were happy to donate part of our Edward Curtis collection to the museum to help educate the public about this important work, and are pleased that the museum was willing to take the collection with a commitment to showing it as part of their permanent collection.

WA&A: Where do you see your collection in 100 years?

R.H.: Most will go to The James Museum so art lovers can continue to appreciate and be inspired by Curtis’ work. As Cardozo said in one of his books, ‘We hope Curtis’ work will continue to change the way our nation views Native Americans and generate a broad-ranging dialogue for greater compassion, understanding, and inclusion.’

Suzanne Driscoll hails from St. Petersburg, Florida, and enjoys writing about art, photography, business, and education.

Diane Hession is a professional photographer in St. Petersburg, Florida, and her award-winning photos have been appreciated throughout Florida and her home state of Indiana.

No Comments