10 May Collector’s Notebook: An Artful craft

In the art world, there is a recognized divide between fine art and fine craft. One isn’t better than the other; there are many highly collectible subgenres and artists in both camps. One could even argue that collectors and museums specializing in fine craft are some of the most intriguing and approachable, partly because the discussion and scholarship includes a dose of anthropological research, which connects this kind of work to humanity in a more approachable manner.

Historically, however, fine craft — such as pottery, weaving, and textiles — has suffered from its connection to function. And because collecting practices by institutions in the 19th and early 20th centuries focused on ethnography, for better or worse, this mindset dictated how such objects were acquired, examined, catalogued, and discussed.

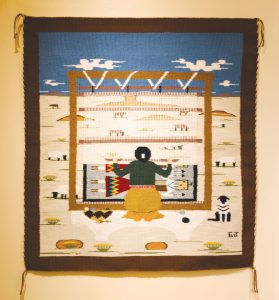

Geanita John (Diné), Weaver at her Loom | Wool: Single-Ply Commercially Processed Wool and Multi-Ply Commercially Processed Wool (Found on Loom); Weft Count: 40-42 Threads Per Inch; Dyes: Aniline and Vegetal (Skirt and Ground Color) | 2007 | Courtesy Jackson Clark, Toh-Atin Gallery, Durango, CO Installation photography by Da Ping Lou, courtesy of Bard Graduate Center

Here’s where things get tricky for modern day collectors. Because crafted objects were often seen as utilitarian artifacts, artistry tended to play second fiddle to function. In other words, we marvel at how people managed without sewing machines and indoor plumbing, yet look past the potter or weaver’s artistic genius. And not only was the artistry in craft overlooked, but artists’ names were not recorded either, a common practice at the time.

Enter curator Hadley Welch Jensen who, in pursuit of her master’s degree and doctorate at Bard Graduate Center (BGC), in New York, was exposed to and became enamored with Native American textiles. When she received the BGC/American Museum of Natural History Postdoctoral Fellowship in Museum Anthropology, a seed began to germinate in her mind. Jensen now had access to the American Museum’s more than 300 textiles that had been collected in 1910 and 1911, catalogued without artist attributions, and stored out of the public eye.

Intrigued and undaunted, in 2018 she embarked on the task of creating an exhibition that would bring these textiles out of storage, many for the first time ever. What she hadn’t planned on was a pandemic. Amid the uncertainty and shutdowns, Jensen’s project took on a life of its own and morphed into a digital deep-dive of Diné (Navajo) cosmologies and culture.

“This art form in particular is a way to tell stories in a space,” she says of these textiles. “This show is a way to think with art and tell stories; to ask, what can we draw out from pieces held in storage?”

As Jensen’s concept for the exhibition Shaped by the Loom: Weaving Worlds in the American Southwest evolved, she took it from a historic look back in time to a collaborative project involving contemporary Native American artists. Fifth-generation Diné weavers Lynda Teller Pete and Barbara Teller Ornelas joined Jensen and brought vital familial understanding to their works. Their knowledge of everything from making looms to sheepherding to harvesting wool, dyeing, and weaving deepened the scholarship and helped train Jensen and her students in ways of discerning a textile’s significance to the point where they could close their eyes and feel the richness of authentic works.

“The great thing about working with living weavers,” Jensen says, “is that they notice particular designs and techniques and are able to draw connections.” And though Jensen’s exhibition hasn’t helped recover names of past artists, she still hopes that someone will come forward with more information about them.

Another Diné artist Jensen worked with was photographer Raphael Begay, who helped turn the exhibit into a digital experience accessible to everyone. The resulting immersive online show includes Begay’s panoramic imagery that helps viewers better understand the topography that influenced historic weavers and contemporary Diné artists.

Still other living artists add further depth, connection, and understanding of the work. “Contemporary Navajo weavers are looking to their ancestors for inspiration. They are returning to traditional yarns and natural dyes, as well as using traditional looms to create new works. The images, however, are reflecting modern life,” Jensen says. Through the next generation of artists, practices such as sheepherding, wool processing, and plant harvesting for natural dyes are passed down and — when you know what you’re looking for — are made apparent in this new work. Passing down traditional weaving practices is what Jensen calls in the exhibition: “Traditional Ecological Knowledge, a uniquely Indigenous approach to understanding and managing relationships between living beings — like plants, sheep, and humans — and the environment.”

Taking tradition to a new level, many contemporary Diné artists think of their works as modern storytelling that embraces tradition and allows them to stretch into different structures, mediums, and forms that have meaning for modern Native Americans.

Ultimately, Jensen says, “It’s powerful to be reconnected with living, breathing, animated works of art. They embody so much.” And though her academic training dictates that exhibitions should be about teaching, she sees a larger opportunity. “I was more interested in providing an opportunity to shape an experience and inspire. By making these things visible, we are inviting people to engage and learn a new way of seeing.”

No Comments