04 Jan Collector’s Notebook: Falling for Forgeries

We love juicy art forgery stories. Those tales of deception and greed, peppered with dubious criminal figures, add a sense of adventure to a sometimes sleepy industry.

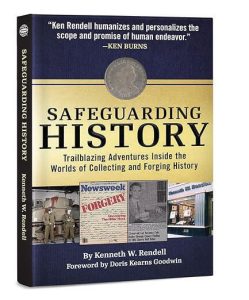

Kenneth Rendell, one of the foremost authorities on and authenticators of historical documents — and the great spoiler of some of the most audacious forgeries ever — released a 2023 memoir, Safeguarding History: Trailblazing Adventures Inside the Worlds of Collecting and Forging History. The book takes us behind the scenes as Rendell debunks the Hitler Diaries, the Mormon letters and murders, and the Jack the Ripper diary hoax, among other mysteries. He also shares how he meticulously curated renowned private and public libraries across the country to earn the title of “greatest collector in the world,” according to historian Stephen Ambrose.

In this column, Rendell discusses his work in historical documents and why he’s so passionate about setting the record straight. He also shares advice so collectors can avoid being hoodwinked. “I’m in a world where you have to be very careful about what you’re doing,” Rendell says. “I always have to be vigilant.”

Objects of Desire

Any serious collector of historical works, from important documents to fine art and antiques, will tell you that the market is riddled with forgeries. In the world of collectible objects, numerous conditions set the stage for forgers to succeed. When you know what you’re looking for, forgeries often reveal themselves as bad knock-offs. And yet, even when all signs point to fakery, why do seasoned collectors fall prey to swindlers? According to Rendell, it often comes down to human behavior and wishful thinking.

“I think the key to it is self-analysis,” Rendell says. He suggests collectors develop a healthy inner skeptic when considering the purchase of historic objects. Start by asking yourself what you want from the purchase — if you’re hoping to make money or beat out the competition, for example — and then think about what factors will make you go through with the deal. “That’s where you’re vulnerable,” he says. “That’s where you’re not being careful enough.”

The bogus Hitler Diaries and Jack the Ripper diary are excellent examples. The Hitler documents were brought to light by a reporter who wanted to break the story and who had ties with the Nazis. The editors at Newsweek, who were about to publish the diaries, were thrilled they were beating out Time magazine for the scoop. Similarly, with the Jack the Ripper diary hoax, Time Warner was focused on the prospect of selling hundreds of thousands of copies. “It blinded them,” Rendell says. “Jack the Ripper was so wrong.”

As a professional, Rendell can cut through the hype and hone in on the troubling issues that are often painfully obvious. In the case of Jack the Ripper’s diary, he offered 25 forensic reasons why the manuscript was a fraud to the British publisher who had bought the forged documents for a sum that he probably couldn’t afford. When Rendell asked to talk to the person who first discovered the manuscript, the publisher responded that he was dead. “The critical person is always dead in these situations,” Rendell says. “The publisher [who purchased the diary] said to me, and he said it in a really sad way, ‘You don’t understand, this is my winning lottery ticket in life.’ That’s what he was grasping, this winning lottery ticket. The people doing the fraud contacted the right kind of person to get it into the marketplace, someone who would latch on to it as the greatest thing that could happen.”

Follow Your Nose: Provenance

Another critical component to authenticating historical works is provenance. Think of this as an object’s paper trail. This is where collectors need to be wary.

“I used to say to other dealers,” Rendell says, “always think about what you’re going to say to the FBI when they sit there and ask you how in the world you think you could have gotten title to this? What are you going to tell them?”

In other words, if it’s too good to be true, ask more questions. Come right out and ask dealers how they know the object is genuine, Rendell suggests. And he recommends only working with people you can take to court if things go sideways.

Provenance, however, is getting trickier because forged documents have slipped into libraries and collections and, because no one questioned them, have become accepted over time. “I just saw a forged Oscar Wilde manuscript — it was atrocious. I could have done a better job. It didn’t look like Oscar Wilde,” Rendell recalls of a document placed in a library’s collection in the 1920s. “Nobody really compared writing samples; that manuscript slipped into the collection before people were intelligently looking at things. How many documents get into libraries, then somebody writes about it, and subsequent researchers don’t look at the original material but base their research on what other people wrote?”

Trust, but Verify

Rendell does admit that his cautious nature has probably cost him the opportunity to buy a few authentic documents, but he says he prefers to err on the side of caution. “I don’t think I’m overly suspicious, but honestly, I think it adds to the enjoyment; you have a much nicer relationship with people if you are really considering them.”

The other thing, he adds, is that collecting is an intellectual process and an escape from the horrible news that’s going on in the world today. “You go to a museum to look at paintings, and it changes your mood. You read books, and you feel good, so your guard is really down. These are places in which you don’t ever have to have your guard up.”

Besides, most collectors are honest and would never think of defrauding someone. “It occurred to me, in the old days in New York when muggings were such a problem, that good people are scared to death in a mugging — they’re the deer caught in the headlights. But the mugger is relaxed. They control the timing. They have an enormous advantage.

“My whole life has been about the complexities of human nature — good and sometimes bad. Understanding the people on the other side of something is always so important. You need to think like them,” he says. “It doesn’t mean you become them.”

Dig Deeper: Book Recommendations

In addition to Kenneth Rendell’s 2023 memoir, here are some books on the fascinating topic of forgeries and fakes…

Forging History: The Detection of Fake Letters & Documents by Kenneth Rendell (University of Oklahoma Press, 1994): This standard reference book educates collectors on the commonalities most forgeries share so they can be detected.

Priceless: How I Went Undercover to Rescue the World’s Stolen Treasures by Robert K. Wittmann with John Shiffman (Crown, 2011): This book is a wild ride-along with the FBI agent who established the FBI Art Crime Team and caught countless art thieves, scammers, and black-market traders and rescued some of history’s greatest treasures.

Provenance: How a Con Man and a Forger Rewrote the History of Modern Art by Laney Salsbury and Aly Sujo (Penguin Books, 2010): One of the 20th century’s most audacious frauds, this book reads like a thriller that details how hundreds of forged works found their way into museums and private collections around the world.

I Was Vermeer: The Rise and Fall of the Twentieth Century’s Greatest Forger by Frank Wynne (Bloomsbury USA, 2006): This book shares the tale of Hans van Meegeren, the disillusioned Dutch painter who turned to forgery and won the patronage of Nazi leader Hermann Göring.

Caveat Emptor: The Secret Life of an American Art Forger by Ken Perenyi (Pegasus Books, 2012): An art forger tells the story of his 30-year career creating fake paintings that went on to sell at both Christie’s and Sotheby’s until the FBI brought him down.

The World’s Greatest Collector

Recently, at a dinner party, Rendell was asked to speak about his work. He began by saying, “You know what you learn from reading other people’s mail? Everyone’s teenagers are a pain in the ass.” The room lit up, of course, because almost everyone could relate. “Dwight Eisenhower,” he continued, “wrote to his wife almost every other day during the war. He was talking about what’s happening with their son. His letters, they’re very human. It’s quite fantastic, everything is handwritten.”

Rendell then told the dinner guests about a letter George Washington wrote to a friend, confessing his fear that people had put him on a pedestal, that he didn’t win the war, the soldiers did, and that people were expecting so much of him, he could only fail. “Dwight Eisenhower,” Rendell says, “wrote out on presidential stationery that that is exactly how he felt, ‘Everyone credited me with winning the war, which is just unfair. And they expect so much of me as president that I can never fulfill these ideas people have.’”

Though the sensational forgeries jump off the pages of his memoir, it’s Rendell’s deep reverence and passion to preserve the words and deeds of historical figures that drive him. “My ultimate goal is for people to understand each other as human beings and to understand how much more we have in common. To get involved with my work, you have to be interested in something other than yourself. If more people were open about their feelings, they would find out they’re not nuts. People would feel a bond. You can have different opinions and not see the other person as a villain. If you read letters of other people in history, you see them as real people.”

When his daughter was young, she asked Rendell if he believed in ghosts. “Now this is a question where you’re going to disagree,” he recalls. “But I said, ‘Yes, I do.’” Taken aback, his wife admonished him, but he insisted, explaining that his vast collection of historical documents and manuscripts was indeed filled with ghosts, their words, and deeds, and they spoke to him through time. “All those things are alive, and their spirit is alive today.”

Rose Fredrick shares her extensive knowledge about the inner workings of the art market on her blog, The Incurable Optimist, at rosefredrick.com.

No Comments