10 Jul Collector’s Notebook: Rematerializing Our Cultural Heritage

For many of us, a trip to Egypt to view the rich tombs of the pharaohs would be a dream come true. The same longing applies to other sites of important ancient history, remarkable architectural achievements, and centuries-old works by master artists. Museums and exhibitions, where we can gaze at fragments of these remains and learn about long-ago cultures, draw huge crowds.

In places where world treasures can be seen in their birthplaces, the global rise in tourism has put many at risk. In 2010, 14.7 million visitors descended upon Egypt. With some fluctuations because of political conflict, those numbers continue to rise. Oumnia Boualam, country director for Egypt at Oxford Business Group, told Daily News Egypt in April 2018 that tourism in that country could “reach 60 million tourists in the next 10 years.” Similar increases in tourism are growing worldwide. Disintegration due to pollution exposure, age, natural disasters, imperfect restorations, and colonial practices of taking artifacts have degraded fragile sites. And in some places, ongoing conflicts have caused the destruction — both intentional and unintentional — of important artifacts and sacred places.

The reconstruction of the Hall of Beauties with the color and missing sections digitally and physically restored. Photo ©Oak Taylor Smith for Factum Foundation

From this information, questions arise. Is it better to visit the original and contribute to its destruction, or to be part of a new approach that presents a replica often more complete than the original that appears today?

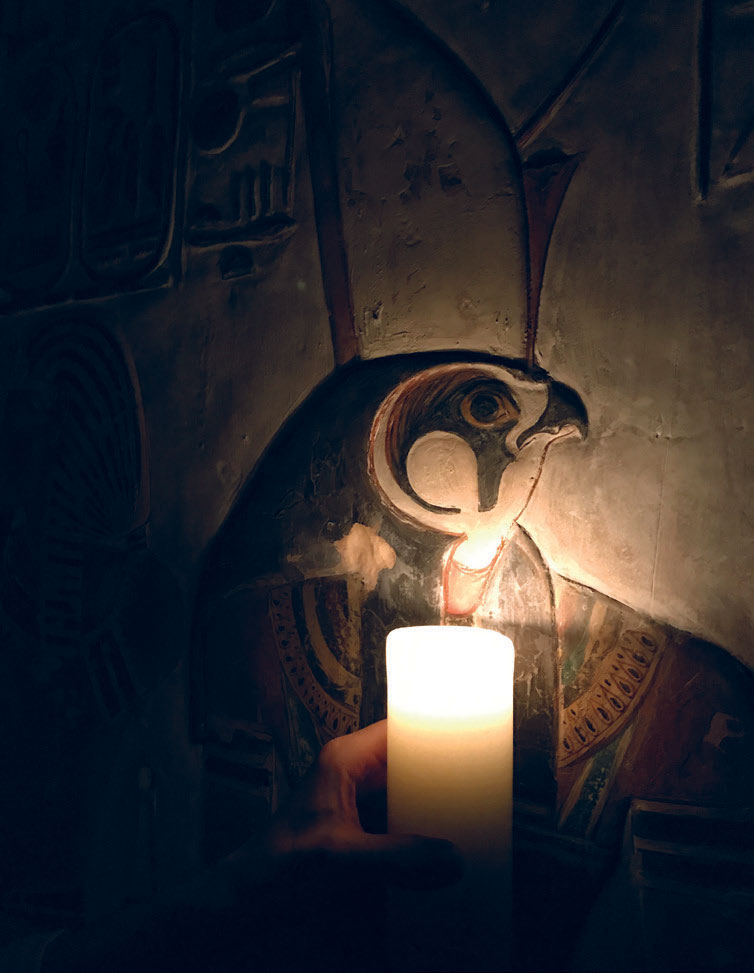

A detail from the reconstructed Hall of Beauties as it may have looked in 1817, illuminated with candle light. When seen with this light, the relief carving is critically important in creating the form; the white paint is matte and absorbs the light while the colors have varying degrees of reflectivity. Photo: ©Oak Taylor Smith for Factum Foundation

Factum Foundation for Digital Technology in Conser-vation was founded in 2009 in Madrid, Spain, and now — with ateliers in London and Milan — the organziation has stepped up to bring cutting-edge technology to the production of facsimiles of the world’s cultural heritage sites. Working in conjunction with its sister company, Factum Arte, it has developed sophisticated equipment, high-resolution recording, and rematerialization techniques that not only show us images of sites and masterpieces as they are today and when they were first established, but also provide surfaces that replicate every crack, texture, brushstroke, and variation of the original.

Factum Arte consists of a team of dedicated artists, technicians, and conservators. Their rigorous methodologies include the Lucida 3D scanner (designed by Spanish artist and engineer Manuel Franquelo) that records 100 million measured points per square meter; computer-controlled routers that process data to carve an object’s precise shape and surfaces; flatbed scanning to recover colors used in masterpiece paintings; and a system able to record ancient manuscripts and books that can only be partially opened. All systems used by the Factum Foundation meet the highest conservation standards. Factum’s founder, Adam Lowe, emphasizes that “transferring these technologies and training local teams to record and rematerialize fragile sites is an essential part of our mission. All data obtained in these processes belong to the owner of the objects, not to Factum.”

A panoramic composite photograph stitched together before perspectival correction. Photo: ©Gabriel Scarpa for Factum Foundation

The Theban Necropolis Preservation Initiative (TNPI) is a partnership between the Factum Foundation and the University of Basel in Switzerland, under the supervision of the Egyptian Ministry of Antiquities. Its founding goal was to protect the integrity and sustainability of tombs and access to Egypt’s Valley of the Kings for future generations.

Abdel Raheem Ghaba, Amany Hassan Mohamed, and Mahmoud Salem working with two Lucida 3D Scanners in 2019. Photo: ©Gabriel Scarpa for Factum Foundation

In 2009, Factum Arte set out to record the tomb of Tutankhamun — King Tut, the Boy King. In 2014, the complete facsimile of the burial chamber was installed at the entrance to the Valley of the Kings. It was the first stage of a larger project that involves the recreation of the tombs of Seti I, father of Ramses the Great, and Nefertari, an Egyptian queen.

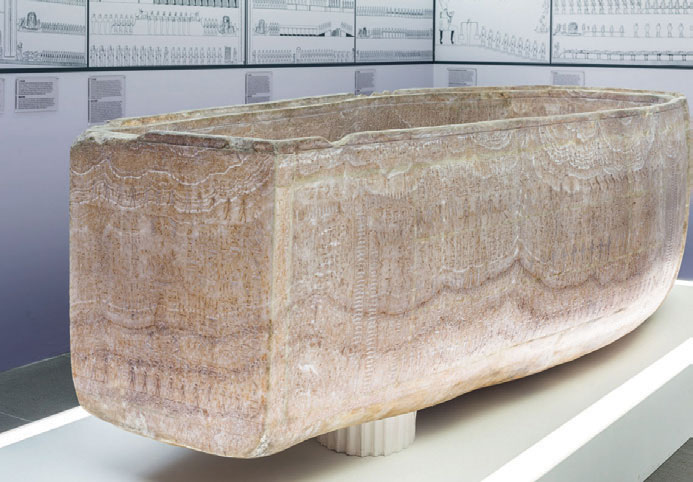

The rematerializing of the rock-cut tomb of Seti I [1323–1279 B.C.] is a notable example of a long-term TNPI project being brought to fruition. It’s especially notable for its 10 chambers of refined bas-relief wall paintings, decorated with thousands of hieroglyphs, and Seti’s elaborately carved alabaster sarcophagus. In 1817, more than 3,000 years after the pharaoh’s death, Italian explorer Giovanni Belzoni discovered the tomb. Awed by the wall paintings, he created a detailed series of watercolors that have proven invaluable for researchers. Unfortunately, Belzoni removed the magnificent sarcophagus; throughout Egypt, in earlier eras, archaeologists, explorers, and others hacked away pieces of walls and carried off objects to establish what are now famous Egyptian collections abroad. In addition, since that time, Seti’s tomb has suffered severe decay due to flawed attempts to preserve it and problems caused by tourism.

Restoration of Stoppelaëre House. The work to restore the building and convert it for its new use was carried out by Tarek Waly Center Architecture and Heritage using local builders and other workers. Financing was provided by Factum Foundation and Tarek Waly Centre Architecture and Heritage. Photo: ©Factum Foundation

In 2016, the TNPI began to recreate the tomb of Seti I and the Seti I sarcophagus. The facsimile includes portions presently missing and held worldwide in museums and private collections. These have been recorded, reproduced, and reassembled to make the replica more complete than the original. In 2017, when the facsimile of two of the chambers — the Hall of Beauties and the Pillared Room — were complete, they were displayed at Antikenmuseum in Basel, Switzerland. They are currently in store in Madrid awaiting delivery to their final destination. As of 2019, Factum is back in Luxor resuming the recording of the tomb of Seti I. When this project is complete, all those who visit will be contributing to the well-being of the local community and the survival of the knowledge contained in one of the most distinguished tombs in the Theban Necropolis.

The facsimile of the sarcophagus was exhibited at Scanning Seti: The Regeneration of a Pharaonic Tomb (October 2017 to May 2018) at Antikenmuseum Basel and at Images of Egypt at the Museum of Cultural History in Oslo (September to December 2018). Photo: ©Oak Taylor Smith for Factum Foundation

The digitization of archaeological evidence, paintings, sculptures, early books, and manuscripts plays an essential role in allowing art lovers, historians, and scholars more opportunities to appreciate and study cultural heritage. Facsimiles installed near their original locations can provide relief for over-visited sites and educate visitors about their history and importance.

Factum Arte has worked with the Musée du Louvre, the British Museum, the Pergamon Museum, Museo del Prado, Biblioteca Nacional de España, the Fondazione Giorgio Cini, the Supreme Council of Antiquities in Egypt and many other institutions and private individuals, and its technologies are also available to contemporary artists.

No Comments