09 Jan In the Studio: A Tradition of Taos Excellence

When artist Mark Maggiori attended Académie Julian in Paris, he’d never heard of the Taos Society of Artists. The venerable art organization, founded in 1915, was where Joseph Henry Sharp, Bert G. Phillips, Ernest Blumenschein, Herbert Dunton, Oscar E. Berninghaus, and Eanger Irving Couse, the six founding members, developed an American art movement that combined the best of European painting techniques with the landscape, effervescent light, and Native American and Spanish cultures that were distinct to Taos, New Mexico.

Maggiori uses a full-length mirror to gain a different perspective on works in progress.

Aspects of Maggiori’s life parallel the lives of the famed Taos founders. Blumenschein, Phillips, and Sharp also studied at the Académie Julian before they helped form the organization. And in 2020, more than 100 years later, Maggiori found himself painting in Sharp’s studio while his own Taos studio was under construction.

After graduating from the Académie Julian, which integrated with ESAG Penninghen in 1968, Maggiori began his artistic career painting portraits influenced by John Singer Sargent. “At that time in Paris, 2004, it was not easy to make a living when painting in a Realist manner; contemporary art was popular. I realized I could not sustain a career, so I put painting in my dream box,” he says.

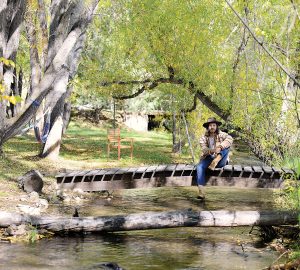

Taking a break from painting, Maggiori relaxes near the Rio Lucero that runs through his property.

Instead, Maggiori explored other creative mediums. He formed the successful nu metal band Pleymo, became an accomplished director, and participated in other disciplines, including animation, graphic design, and photography.

“I was forever interested in American culture. I visited often, photographing for my band, which allowed me to become acquainted with cowboy culture. What I didn’t know was that there was an art form to it, which I discovered later on,” Maggiori says.

When Maggiori lived in Paris and was directing a music video for a French artist, he met American Petecia Lefawnhawk. “She was working for a fashion company as an art director. I hired her for videos I was doing as she happened to be cool and efficient,” Maggiori says, adding that 12 years later, and after he moved to the U.S. in 2011, they were married and now have a daughter.

A thunderbird emblem marks the double doors that allow Maggiori to maneuver his large canvases in and out of the studio.

Meeting Lefawnhawk also greatly impacted his artistic career. Her father lived in Oklahoma and introduced him to Western art. “When I visited Oklahoma wearing a cowboy hat, my father-in-law challenged me as a French man wearing a cowboy hat. He told me if I wanted to see what real cowboys are like, I should go to the National Cowboy & Western Heritage Museum in Oklahoma City. Thank God he sent me there! When I got there, I was struck by lightning! I spent a lot of time in the gallery looking at all the Prix de West winners.

“That was when I felt a calling. I had a feeling, ‘I can do that, and I can do it well.’ There was so much that was speaking to me — the art form, the landscape, the cowboy clothing. I bought magazines and learned that there were people buying this art. Thereafter, when we went and spent time in Oklahoma, through 2012 and 2013, I visited the museum often. I was involved in my career as a director and couldn’t just stop; I wanted to make sure if I was to change my career that it was possible to make a living, not be like the poor artists in ‘La Bohème.’”

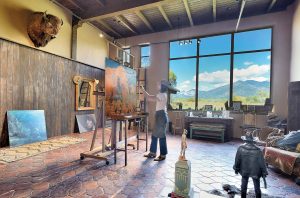

“Mixing paint is where an artist spends more time than actually touching the canvas with a brush,” Maggiori says, adding that 85 percent of his time is spent mixing paint and 15 percent is spent deciding where it should go.

In 2014, he painted his first cowboy, an epiphany that spurred the creative direction of his life. The music video industry had changed, and the calling he’d felt to Western art became a reality.

At first, he began posting his paintings on Instagram. “I was solo; I didn’t know any artists, but I ended up meeting some through social media. When I started painting cowboys, I posted on Instagram; people responded, giving their opinions. I enjoyed the interaction,” he says, adding that he found encouragement and help from other artists, such as Cowboy Artists of America member Teal Blake. “If I posted a painting with something not correct, [Blake] would poke me. ‘Be careful of this or that.’ I was learning a lot of things; coming from France, it was helpful.”

Entering the studio, a collection of cowboy boots and Navajo blankets lives underneath Maggiori’s print The Seeker.

As a new artist, he began looking for a gallery, “but I didn’t dare approach one,” Maggiori says. “At some point, [Maxwell Alexander Gallery] sent me an email inviting me to show them my work. I loaded some paintings and drove to L.A. They bought the paintings on the spot and took them to Montana for a show. Both paintings sold, and from there, they asked for more. As they were selling my paintings, other collectors, galleries, and shows began to approach me. All of a sudden, I was in shows; it happened so quick!”

The Briscoe Western Art Museum’s Night of Artists presented Maggiori with its patrons’ choice award during his first show with them in 2016, followed by an award for best painting in 2017. Then, the esteemed Autry Museum of the American West presented him with the Don B. Huntley Spirit of the West Award at the Masters of the American West in 2018 and again in 2019. His career was in full swing.

Generous-sized windows frame the mountains sacred to the people of Taos Pueblo, El Salto, and allow plenty of natural light to filter through the studio.

Maggiori’s initial insight that he could excel at Western art was well calculated. Today, his paintings are considered to be among the best for “New Western art,” a movement Maggiori believes was started by the Southern California-based artist Logan Maxwell Hagege.

“Logan brought in a new era. It was an interesting time for renewal, and I think that’s why it was so fast. Glenn Dean and others came along, too. Collectors were hungry for new blood — we had something new. Our generation had different techniques garnered from watching animations, from comic books, and for me, lots of inspiration from motion pictures.”

With a love of vintage American cars, Maggiori sits in his 1966 Chevrolet Malibu; to the left is his 1966 Ford F-250.

During the 2020 pandemic, Maggiori and his family fell in love with a property in Taos, much like the original founders of the Taos Society of Artists felt when they first came to the region. They bought 5 acres and converted a three-car garage on the property into a studio, with plenty of natural light and views of the mountains.

While the studio was undergoing renovations, a friend who managed the Couse-Sharp Historic Site suggested that Maggiori paint in Sharp’s studio while the campus was closed for the pandemic. “I ended up working there and then did a show of paintings from the studio with Parsons Gallery,” Maggiori says. He now divides his time between his Los Angeles and Taos studios.

Maggiori stands near a marsh on his property, overlooking the distant mountains.

Maggiori is looking forward to his upcoming solo exhibit, Beyond the Golden Sky, at Legacy Gallery in Scottsdale, Arizona, opening on March 10. The show represents two years of work. “It will have about 20 pieces, 13 to 14 [larger ones] and also smaller works that will have different price points for different collectors,” says Maggiori. Due to demand, some of these pieces will be sold by a drawing, while others will be sold during a live auction, promising a lively evening.

“Every so often, an artist will come along with a new fresh look at a familiar subject,” says Brad Richardson, owner of Legacy Galleries. “Mark Maggiori is a great example of this; he has been able to do this in a short period of time. Collectors have aggressively embraced his paintings. In my 35 years of experience, I feel Mark’s work will stand the test of time.”

A favorite painting in the studio is Maggiori’s rendition of his daughter, Wilderness, at 2 years old; it’s the only original painting that he’s kept. “I told her I was going to paint her every year, and now she is 3, so I must think of how I want to paint her,” he says.

WA&A senior contributing editor Shari Morrison has been in the business of art for more than 40 years; she helped found the Scottsdale Artists’ School, the American Women Artists, and directed the Santa Fe Artists’ Medical Fund for some years.

Based in Santa Fe, New Mexico, photographer Daniel Nadelbach’s clients include Smithsonian, Whole Foods, Auberge Resorts, Head Sportswear, and Vogue Australia, among others.

No Comments