10 May In the Studio: At Home with the New Western Iconographer

For more than a decade now, Logan Maxwell Hagege has been riding high as one of the most esteemed portrayers of the American West. His cleanly contemporary, elegantly stylized, vibrantly toned scenes of vast landscapes, soaring cumulus-crowned skies, perfectly rendered cacti and flowers, and serenely self-possessed Indians and cowboys have created an indelible new iconography for the region. In the process, he has played a major role in attracting the latest generation of collectors to an art genre that began in the late-19th century, with Western greats like Frederic Remington and Charles Marion Russell, and feels more vital than ever today.

An early New Mexican wooden chest behind his pair of club chairs holds a collection of Navajo blankets Hagege uses for his paintings. His son’s painting of a horse wearing a cowboy hat leans atop a corner of a shelf just to the right of the window.

Yet, for all his burgeoning success, until five years ago Hagege (pronounced Ah-jejj) had long worked in less-than-ideal places. “My first studio was a corner of my parents’ cluttered garage,” says the native Los Angeleno, who grew up in the San Fernando Valley and segued to a succession of spaces that included an old garment mill in Fall River, Massachusetts; a “spooky classroom in a creaky old early-1800s schoolhouse” near a graveyard on Cape Cod; a brief return to his folks’ garage; and a place in another part of the Valley across the street from a marijuana dispensary that was robbed one night. “And the SWAT team wouldn’t let me leave the studio for hours,” he says. “That’s when my girlfriend, Misty, who’s now my wife, said, ‘It’s time to move.’”

Hagege bought the 1978 Ford pickup for local chores like “picking up hay for our sheep. It never leaves Ojai.”

Eventually, the Hageges, with their son, Wild, about to start preschool and Misty seven months pregnant with their daughter, Poppy, decided to head an hour’s drive west to Ojai. The beautiful, sheltered valley, just 15 minutes inland from the Pacific Coast and due east of Santa Barbara, has long been a retreat savored by artists, celebrities, and seekers. Director Frank Capra set his 1937 film based on John Hilton’s best-selling novel Lost Horizon here, with the valley standing in for the mystical Asian mountain kingdom of Shangri-La. Dada potter Beatrice Wood established her home and studio here in the late 1940s, following her Indian spiritual leader Krishnamurti to the enclave. Today, music lovers flock to the town each June for the Ojai Music Festival, four days of groundbreaking live classical, avant-garde, jazz, and experimental performances.

A good friend crafted the patio picnic table from local fallen trees.

Logan and Misty Hagege and their children settled here in a circa-1985 Spanish Mission-style house on 5 acres, in a quiet semi-rural neighborhood with mountain views. A short stroll away, he erected a barnlike, 2,000-square-foot insulated steel structure 24 feet tall “that sort of fits into the rural setting,” he says. “You’d never know it’s an art studio.” Yet, inside, the space is perfectly appointed for just that purpose, with drywall where paintings can hang, daylight-balanced LED lighting, a custom 8-foot window to welcome natural illumination, and a loading bay with a giant roll-up door for sending out larger works.

The artist’s sketchbooks cover many of the studio’s tables.

On an adjacent patio with built-in picnic table, Hagege can host groups of friends or collectors, surrounded by a recently planted cactus garden he hopes will grow to provide convenient living references for some of his works. Beyond, there’s a chicken coop he built as a project during pandemic isolation; and three sheep roam the surrounding meadows, helping to keep the grass at bay.

Family plays an important part in Hagege’s studio, from a small easel for his children, Wild and Poppy, to the pink-backgrounded Mistified, a portrait of his wife, Misty, wearing a Western hat, painted by his friend Billy Schenck.

Back inside, Hagege now has room for everything he needs to produce his art in spacious, convenient, secure comfort. One end features an expanse of low bookshelves he had built to contain his reference library of about a thousand art books spanning “a good scope of art history, including many on the West.” Steps away is an expansive table where he frames his art, starting with frames built to his specifications, along with flat files “to keep my drawings safe.”

Hagege works on part of the background of the painting for his documentary, which is destined for the film festival circuit in 2024.

Signs of the art-world friendships that have sprung from Hagege’s generous-spirited enthusiasm for other artists working today can be found in the studio’s small bathroom. Here, hanging ceiling-to-floor, is an assortment of framed works by artists including Jeremy Lipking, Brett Allen Johnson, Len Chmiel, Ned Jacob, T. Allen Lawson, Josh Elliott, and Billy Schenck, interspersed with a few paintings by past greats like Maynard Dixon. The choice of venue intends no disrespect. “I don’t want to be sitting at my easel, look over, see a great painting, and feel bad about what I’m doing,” Hagege laughs.

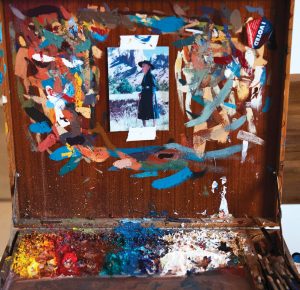

On the inside of his palette lid, spots where he has wiped off excess paint from his brush form an unintentional abstract design.

In a corner of the studio close to the large window is that easel: a Hughes Model #4000. The large, sturdy, counterbalanced wooden stand “makes working on big, heavy paintings a lot easier,” he says. “It’s the Cadillac of easels.” On a small, high bench to its right sits his well-worn, custom-made wooden palette box — “I’ve had it for maybe 15 years” — with, masking-taped inside its lid, a postcard of Georgia O’Keeffe outdoors at her Ghost Ranch outside of Abiquiú, New Mexico. “She’s there as a reminder to take some chances and be gutsy.”

The painting Close to Home, resting on the floor, led to a serigraph display above it to the right, produced in an edition of 9, and also served as an inspiration for one of Hagege’s first sculptures, the aluminum, steel, and enamel-paint work display on the shelf, entitled Blue Bandanna.

A coffee table nearby holds an assortment of the pocket sketchbooks Hagege always carries with him wherever he goes. “I have a ton of them, for little stream-of-consciousness drawings, plucking ideas out of the air. Some of them will turn into paintings, or elements of paintings, or maybe spur another idea.”

Behind his Simpsons figurines is a study the artist framed.

But Hagege isn’t the only one hard at work developing art in his studio. Near his own easel stands a miniature one with pots of tempera paint and little brushes. “My kids will come in here and paint with me. I think it’s important for them to have a place where they can just be messy and have endless supplies.”

Two figure drawings in a series of working studies will eventually lead to a new painting Hagege is planning, to be entitled A Day in the Life.

Traces of Hagege’s personal life are interwoven with his working one throughout the studio. On the other side of the large window from his easel, for example, is a rack in which more than a dozen different surfboards stand on end, two of which Hagege made himself. “I used to surf every day when I was in my late teens and early 20s,” he says. “Now I try to get out about once a week.” On top of the bookshelves stands an assortment of collectible character figurines from the early days of “The Simpsons” animated TV series, reflecting his early ambitions of becoming an animator before serious atelier-style art training in his early 20s altered his career path. “When I was a kid, I was always into collecting,” Hagege says.

A dozen chickens now reside in the coop Hagege built during the pandemic. “I have no plans to draw them yet,” he says, “but you never know.”

He works on a frame for Hinoki Clouds, a painting he created as a wrapping paper design for a friend’s company.

Hagege holds one of his studies for the painting he produced as one of three artists — along with Bella McGoldrick and Thomas Blackshear — who were selected to reimagine The Last Drop from His Stetson for the labels of limited-edition hats that were produced to commemorate the 100th anniversary of Stetson’s iconic image originated by Arizona painter Lon Megargee.

In ways like this, small and large alike, Logan Maxwell Hagege’s studio encapsulates not just his work as an artist but his life as a well-rounded human being. And he feels the benefits of that fact, every day. “Studios have always been an important part of my life,” he says. “Even if I’m not working, I’ll sometimes come out here and sit around and do nothing. It just feels good to be here.”

The wide-ranging display in the studio’s bathroom includes, at top-left on the right-hand wall, Hotline by Jemez Pueblo artist Jacque Fragua; and, in the antique Craftsman frame two below it, a work by Maynard Dixon.

Hagege’s work is represented by Maxwell Alexander Gallery in Los Angeles, California; Gerald Peters Gallery in Santa Fe, New Mexico and New York, New York; Mark Sublette Medicine Man Gallery in Tucson, Arizona; Trailside Galleries in Jackson, Wyoming, and Scottsdale, Arizona; and Wood River Fine Arts in Ketchum, Idaho.

Hagege created The Song at Sunset, his largest work to date at 96 x 144 inches, for a 2020 show.

Two color studies setting the same foreground against different backgrounds help him decide on what composition he will paint.

No Comments