11 Mar In the Studio: From Cows to Canvas

Joel Ostlind’s subject matter reflects the glorious diversity of the Rocky Mountain West, encompassing cowboys, horses and cattle, wildlife, fly fishing, and the great outdoors itself. So it stands to reason that his ideal studio would offer a literal window into that expansive world, a well-sheltered place endowed with sweeping vistas and ample space where he could draw, engrave, print, and paint the world he knows and loves.

Ostlind began building such a space for himself around 30 years ago. The studio stands near a pond that’s less than a hundred yards’ stroll from his vintage 1930s home in the Little Goose Valley, about two miles outside of Big Horn, Wyoming, population 495, and two miles from the Bighorn Mountains, a spur of the Rockies. He first began working in his studio in 1991 and has continued to improve and expand it over the years, custom tailoring it to fit his particular needs as an artist.

Shining outward at night, the large lofted windows in the original studio structure bring northern light into his print room. In the lower-roofed building to the right, Ostlind’s wife Wendy frames his artworks, and to the left is the studio’s newest addition, a hay-bale structure where he paints.

“As the late William F. Reese, a wonderful Western painter, once told me, ‘When inspiration hits, you’d better be standing in front of that easel,’” says Ostlind in his soft-spoken, measured manner. “A studio has given me stability. I can go to it, and I’m in the art world. It has also given me depth, because I have a pile of old sketchbooks where I can always find something for reference. Since I draw every day, the studio is just part of the pattern for me. And it filters out some of the distractions of the world.”

- To create an etching, Ostlind heats a copper plate and then uses a small roller to coat it evenly with his etching “ground,” a combination of beeswax and asphaltum, a coloring agent.

- For his etching tool, he uses a piece of an ordinary straight pin that he sticks into a pencil eraser. He removes the wax, and then exposes the metal to an acid bath to etch his drawing into the copper.

- In the final step of this creative process, Ostlind lifts a completed print off an etching plate on the bed of his Ettan press.

For many years before he settled down near Big Horn, Ostlind made his studio wherever he happened to be resting his head for the night as a working cowboy. Born and raised in Casper, Wyoming, he’s always loved both art and the cowboy life, and he took watercolor and basic design classes at Casper College before earning degrees in soil science and ranch management. Straight out of college, he began working on ranches.

One year in his 20s, as the holidays approached, Ostlind was on a ranch in the Texas Panhandle, and his parents sent him a gift box “with a wool sweater, a little electric Christmas tree, and a blank sketchbook.” He resolved then that “every evening, I’d draw something related to the day,” and he still draws daily. “It’s just part of the pattern for me, like musicians playing their scales,” he says.

Ostlind’s studio displays a wealth of items steeped in his cowboy past and lifelong love of the West, including (from left): his easel, a sofa once owned by rancher Bradford Brinton, the first saddle he bought as a working cowboy, his 15-by-30-inch landscape Jackrabbit Flats, and a recently arrived shipping crate, in which the University of Wyoming returned a collection of his etchings that had toured for several years. The wool saddle blankets “are nice to cover up some of the concrete floor, and I’ve always enjoyed red blankets,” the artist says.

From the start, Ostlind’s spare, elegant, accurately observed lines possessed an almost musical lyricism. Later on, in the 1980s, when he, his wife Wendy, and their young son and daughter were in a remote cow camp on the vast Padlock Ranch straddling the Wyoming-Montana border, Ostlind had the chance to show some of his sketches and watercolors to an art director from Leo Burnett, an international advertising agency that was on location to shoot ads for Marlboro cigarettes. “He said, ‘You could do something with this.’ And to hear him say I had some potential felt liberating,” Ostlind says.

The family moved for Ostlind to work on a smaller ranch, where he would feed cattle with a team of horses in the morning and in the afternoons he would teach himself art at the Sheridan County Public Library. In the spring of 1990, with their children school-aged, the Ostlinds bought their current home with the money they’d diligently “saved on cowboy wages,” and, as Ostlind explains, he “started gathering material for a studio, the first part of which I built in the winter of 1990 to ’91.”

In the print room, Ostlind stores completed etchings in flat files that his late father “built for me out of old scrap lumber around 1998.” The artist has organized his studio with separate areas for printmaking and painting.

The 12-by-24-foot structure called for a lot of old-fashioned Western resourcefulness. “I hand-dug the foundation,” Ostlind says. “I traded with different people around the area, including hay off this piece of land for some lumber. The trusses for the lofted ceiling are from trees I cut down that were killed by pine bark beetles on the Padlock Ranch. I got a lot of salvaged building materials, like windows from some demolition my brother-in-law had done. I traded a little art for the picture window. And my father would come down from Montana and help me.”

Near the doorway to the etching studio, Pica relaxes in her bed. “She spends every day in the studio with me and makes a good doorbell,” Ostlind says.

Meanwhile, during a successful show of his pen-and-ink drawings at a bank in Sheridan, Wyoming, Ostlind received numerous requests for “another drawing like the one you sold.” That led to an interest in copperplate etching, a time-honored method of making fine-art multiples. So he took a printmaking course at Sheridan College, and, as he was completing the studio, he bought a high-quality Ettan press with a 20-by-40-inch bed that enabled him to print etchings as large as 18 by 30 inches.

Today, Ostlind still uses the press to produce sought-after limited-edition prints that Wendy frames in an adjacent workroom, applying gold-leaf details to the moldings by hand. But the tidy space of the original studio ultimately proved too limiting for the artist’s painting activities; he needed more space to judge his compositions from afar.

To that end, about a decade and a half after first building the studio, Ostlind set about creating an addition: a structure composed of dried hay bundles 18 inches thick, secured by chicken wire and sealed within stucco. Heading up the project’s design, with Ostlind assisting in construction, was his son Jake, then a recent graduate of the School of Architecture at Montana State University.

In the Heart of Wyoming | Acrylic on Linen | 18 x 18 inches | 2019

The 18-by-30-foot structure has since proven to be an ideal place for Ostlind to paint his acrylic canvases, surrounded by pleasing memorabilia, including the first saddle he ever owned and an antique wood-framed leather sofa with German silver trays in the armrests. That sofa was once owned by Bradford Brinton [1880–1936], whose ranch became the foundation for the nearby Brinton Museum. “I just picture Bradford sitting on that couch with a mixed drink and probably a cigar,” Ostlind says, chuckling.

On the wall that’s opposite his easel, to the right of a picture window framing the Bighorn Mountains, is a small window — its wood frame painted Swedish blue — inset into the wall to offer a glimpse of the chicken wire and hay within. Typically referred to as a “truth window,” this traditional element of straw bale structures proves the veracity of the construction method. “Some people put a real ornamental door over them,” says Ostlind. “La dee dah! I usually just hang a painting over it.”

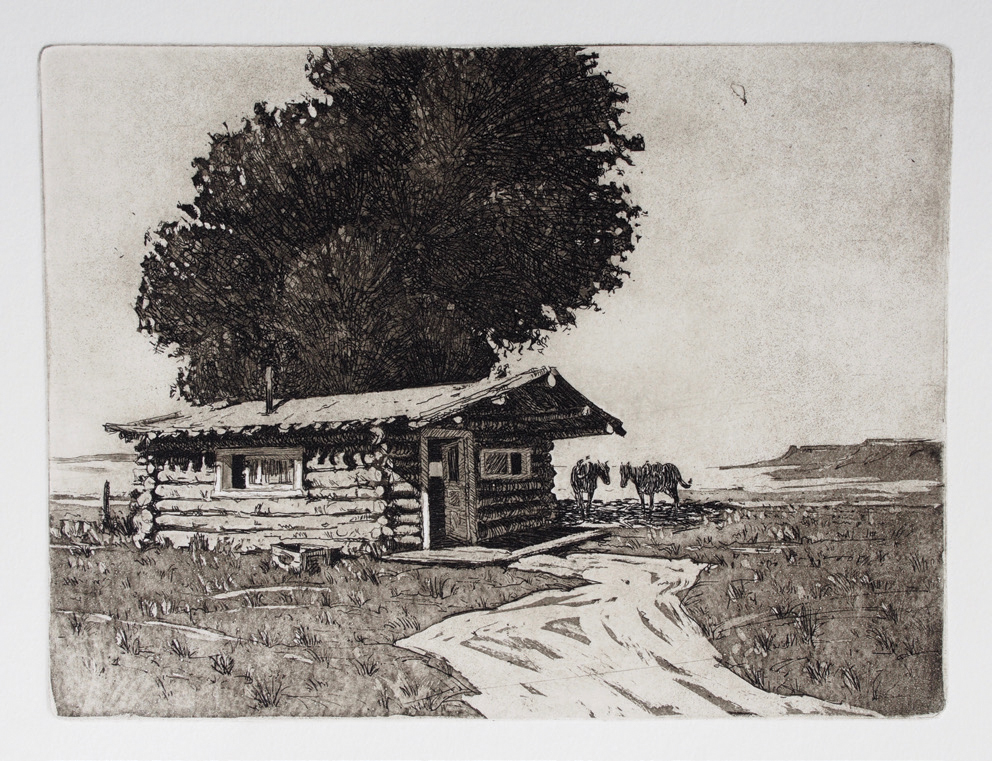

Coffee at the Neighbors | Etching with Aquatint | 6 x 8 inches | 2015

Regardless, the truth window provides an apt metaphor for the artist: Inside and out, in his life and his art, Ostlind is the real deal, a genuine product of the American West.

No Comments