06 Sep In the Studio: Read between the lines

It’s not your average artist who creates a series of paintings that becomes popular, then refuses to sell even one. But Poteet Victory is not your average artist.

Of Cherokee and Choctaw ancestry, Victory, named Robert Poteet at birth, was born in Idabel, Oklahoma. His name is derived from his paternal Cherokee grandmother, Willie Victory. His last-name-turned-first is from his mother’s side of the family, who had a Louisiana Cajun upbringing.

The sculpture garden at Victory Contemporary includes works by Ted Gall, seen on the red bases. The foreground aluminum piece is titled Dancing with the Muse, and the far stainless-steel piece is The Chase.

As an art student during high school, Victory modeled for local artist Harold Stevenson, who would become a lifelong mentor. After moving to New York City, Stevenson became famous for his mural The New Adam, which resides at the Guggenheim Museum.

Victory studied art at Oklahoma University, leaving after his junior year to live in Hawaii. There he mastered the art of silk screening, returning to set up a successful and booming business in Dallas, Texas, working for Frito-Lay, Waylon Jennings, Willie Nelson, and CBS Records. When he’d accumulated enough to pursue his dream of becoming a full-time painter, he sold his business and moved to New York City.

Occupying an 1890 building listed on the National Register of Historic Places, Victory Contemporary Gallery is located in downtown Santa Fe amidst the museum and arts district.

Stevenson prepared an unusual welcome. He had befriended Andy Warhol when he first arrived on the New York art scene. Already an established artist, Stevenson had helped Warhol get started with connections to galleries and museums. He told Warhol about this young artist from his hometown and arranged for Victory to meet him.

Victory tells the story in the newly published biography Poteet Victory, by J. Robert Keating. On a hot day, he boarded a plane in Dallas wearing a straw cowboy hat, headed for New York City. He sat next to a Wall Street broker who, once they landed, asked him what his plans were. “Well, I’m going to meet Andy Warhol,” Victory replied. The broker, wanting to see the result of this declaration, offered to pay the cab fare to Warhol’s Factory.

Victory is at work on a personal commission, an Abbreviated Portrait of a collector. Commissioned portraits can be any size, unlike his series of 20 celebrities, which are all 4 by 4 feet.

Upon arrival, Victory announced himself to the doorman, saying that Warhol was expecting him. “Well, here comes Andy,” says Victory, “with his hands in the air and a big smile on his face, sayin’ ‘Hey… Great! You’re here!’” It turned out that Warhol was going to a cowboy-themed party later that day, and Victory’s straw cowboy hat fit him perfectly.

But instead of attending parties at The Factory, Victory devoted himself to his studies at the venerable Art Students League. He eventually returned to his home state, earning a Bachelor of Fine Arts at Central State University in Edmond, Oklahoma, in 1986.

Victory aims to use color judiciously throughout his compositions.

Today, Victory and his wife, Terry, welcome clients and visitors to their downtown Santa Fe gallery and studio on Palace Avenue. Its prime location is amidst museums and galleries, including the Georgia O’Keeffe Museum and the New Mexico Museum of Art. Built in 1890, the building that houses Victory Contemporary is on the National Register of Historic Places. It has been described by the Historic Santa Fe Foundation as “an excellent example of local adobe construction modified by late 19th-century architectural detail.” The two-story building is recognized by its second-story balcony and the porch’s elaborate woodwork.

The main office of Victory Contemporary features Victory’s work, including 20 mini Abbreviate Portrait prints in plexiglass on the far wall.

The Victorys jumped at the chance to purchase the property in 2019, after paying more than $1 million to lease a gallery for 10 years. Luckily, the building had been purchased and renovated during the 1970s by preservationist and architect John Gaw Meem, who then donated it to the Historic Santa Fe Foundation in 1980.

The couple renovated the building to historical code, including refinishing its wood floors. They removed .25 inches of cement from the steep stairs that ascend to his studio and to a section of the gallery he hopes might one day be a museum for his Trails of Tears mural project. One of the studies for the mural hangs on a wall outside the studio. Outdoors, they have beautifully landscaped a back courtyard into a modern sculpture garden.

Victory sketches some ideas for a series of future stickball paintings.

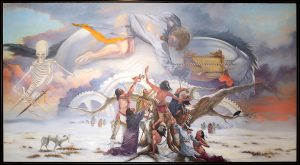

Victory is currently revisiting The Trails of Tears mural. “My dad’s side of the family is American Indian. When I began the mural, I wanted to tell the story of what they experienced,” he says, recounting the experience of J.C., his Cherokee grandmother’s father, who didn’t sign the Dawes Rolls (a government treaty that would end land ownership for five tribes and give each member possession of tribal lands instead) because he and his brother had witnessed their parents’ death by renegade white men. To this day, Victory says that what happened to his family is “still pretty fresh — even after all these years.”

In the main showroom, Victory’s abstract Shards of the First People sets a welcoming tone in the gallery.

The Trails of Tears project might have seemed a quixotic effort to then Oklahoma Governor David Boren when Victory proposed it in 1998, after having spent three years researching and getting the support of the five tribes. The 56-by-16-foot mural in three panels was a vast undertaking, but the blood boiling in his veins gave Victory the impetus to execute the idea.

With Governor Boren’s support, the University of Oklahoma and Victory signed a contract that it would go into the Natural History Museum. They gave the artist an old field house on campus for his studio, “even adding air conditioning so I could work in it,” he says. He began the mural’s three panels in 2000. “But after 9/11 in 2001, a lot of funding dried up,” Victory says, adding that under a new director, the contract was dissolved.

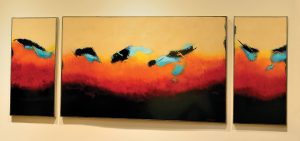

This abstract triptych, Reflections of the Sangres, depicts the Sangre de Cristo Mountains, visible from Victory’s second-floor studio.

For 20 years, the mural was stored in a warehouse. But today, his creative resilience has made him ready to focus on the project once more. “We brought the study into the gallery because I wanted to start raising awareness again about the Trail of Tears,” he says. “I’m donating the large study to the Choctaw Tribe for display in a casino in Hochatown, Oklahoma, where everyone can see it.”

In his studio, Victory is about to begin painting number 21 in a series of abbreviated abstract portraits; it’s a series that has gained wide popularity and one he calls “a little wild.”

The study for The Trails of Tears is an oil on linen and represents the middle panel of the full-size mural, which stretches 16 by 24 feet.

He explains how the Abbreviated Portrait series came about in 2008: “When I first started painting, I was focused on Indian subject matter, which I still do today, but I spice it up a bit by adding texture: sand, beads, leather. Then I started painting in an abstract way, and I wanted to do some abstract portraits. When everybody started texting and using abbreviations like ‘l8r” for ‘later,’ an idea came to me. One day I was doing a white painting with a red center. I began thinking about texting. I went over and put a black mark on it. That was it! Marilyn Monroe.

The very first of the Abbreviated Portrait series features Marilyn Monroe; the white represents one of her famous scenes in “The Seven Year Itch,” along with her iconic red lipstick and beauty mark.

“My mentor freaked out,” he says. “He told me, ‘You’ve no idea what you’ve just done. It’s impossible to come up with something new in art, and you’ve done it!’ Marilyn was the first portrait, then I did Elvis, and I don’t know why but Howard Hughes was the third. Then, Lucy and Dolly Parton. I’ve done 20 so far. I won’t sell them. I hope one day to have them all together in a museum exhibition. We’re working on that right now.”

In the meantime, with the knowledge of how to make a great reproduction, prints of Victory’s portraits are available through Victory Contemporary in Santa Fe.

No Comments