11 Jul Perspective: A Meditative Mood

R.E.C. Chipper Thompson, husband of the late artist Lanford Monroe [1950–2000], remembers a visit they made to Claude Monet’s gardens in Giverny, France. Monet’s house was closed to the public that day, but Monroe wanted to see inside. So, with permission from the guard, Thompson lifted his wife onto his shoulders so she could gaze in the windows. The famed French Impressionist may seem an unlikely inspiration for the American painter’s delicately atmospheric landscapes and wildlife imagery. But Thompson, who was with Monroe for 11 years, saw her awestruck and moved many times by art as diverse as Monet’s water lilies and Robert Motherwell’s abstractions. “A lot of people don’t know the broadness of influences that were behind her paintings,” Thompson says.

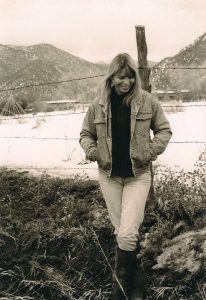

Artist Lanford Monroe [1950-2000] dedicated her life to her artwork and completed her first commission at age 6. She lived with her husband, R.E.C. Chipper Thompson, in Taos, New Mexico.

In this atmosphere, Monroe’s talent was encouraged, and she fully expected to follow an artistic path. After graduating from Huntsville High School in Alabama in 1968, she studied painting at Ringling School of Art and Design in Sarasota, Florida. She then traveled and painted, continuously studying the art of those she admired. Monroe developed a joyous yet extraordinarily dedicated approach to painting. Except on occasional days when a lifelong heart condition lowered her energy — and ultimately took her life at age 50 — Thompson remembers her spending eight hours a day in her light-filled studio at their home in Taos, New Mexico.

The couple frequently traveled to wild places in search of inspiration, often to Yellowstone and Grand Teton national parks. While Monroe’s landscapes almost always include wildlife, they are not portraits of animals front and center on the canvas. Instead, her work reflects what is more often the experience of glimpsing an elk or moose in the wild: first, the feeling of standing among trees or beside a river in the morning stillness and then noticing a magnificent creature entirely at home in that place.

Cold Trail | Oil on Canvas | 20 x 16 inches | 1999 | JKM Collection, National Museum of Wildlife Art. ©Estate of Lanford Monroe

“She produced soft-edged compositions that subtly reveal the relationship between an animal and the environment,” says Maria Hajic, director of the Department of Naturalism at the Gerald Peters Gallery in Santa Fe and former curator at the National Museum of Wildlife Art in Jackson, Wyoming. “She captured the nuances of light, color, and a sense of place and created a meditative mood.”

Hajic knew Monroe for more than a decade, showing her art at the museum and then the gallery. She describes the painter as an “absolutely lovely person, with a soft, Southern charm.” At the same time, Monroe was “totally professional, a dream to work with, and very humble about her art,” Hajic says. She was also just hitting her stride as a painter, honing her signature style and beginning to gain collectors on a national scale. When she died, a major three-artist exhibition at Gerald Peters with Clyde Aspevig and sculptor Walter Matia was two weeks from its opening date.

Adam Duncan Harris spent 20 years as chief curator at the National Museum of Wildlife Art and now serves as the museum’s Grainger/Kerr Director of the Carl Rungius Catalogue Raisonné. Although he joined the museum shortly after Monroe died, he has a strong appreciation for her work, with its “beautiful atmospheric quality” and subtle approach to rendering wildlife. Harris has a particular fondness for a large diptych called The Gathering in the institution’s permanent collection. The two-part painting depicts a group of moose in a foggy forest clearing, each side almost a mirror of the other.

Thompson clearly remembers the day he and Monroe experienced those moose. The couple’s car was in a line of stopped vehicles in Yellowstone, all the occupants watching a bull moose on the side of the road. Eventually, the moose wandered into the woods, and the cars moved on. Thompson and Monroe were about to leave as well when Thompson suggested they follow the animal. They walked — very carefully — into the woods, guessing the moose was far enough away not to feel threatened. Suddenly they saw him, along with another bull and two or three cows among the trees. “We both had the same reaction: We’re stalking moose, like Neolithic hunters!” recalls Thompson, smiling.

Back in her studio, Monroe produced two paintings from her photographs of the moose. When her husband saw the paintings propped against the wall unframed, he immediately imagined them as a diptych, and Monroe agreed. “It’s a great memory,” he says of coming across the majestic creatures. The diptych was in the invitational Prix de West exhibition at the National Cowboy & Western Heritage Museum when the artist died.

The Gathering | Oil on Canvas | 20 x 16 inches | 2000 | Purchased with a grant from the Robert S. and Grayce B. Kerr Foundation as a 2017 Collectors Circle Acquisition, National Museum of Wildlife Art. ©Estate of Lanford Monroe

Maryvonne Leshe, the managing partner at Trailside Galleries and the Jackson Hole Art Auction, represented Monroe at Trailside for more than 20 years. The artist was “really special to work with, a gentle, kind spirit,” she says. “There’s such a peaceful quietness about her paintings — very elegant,” Leshe says. She remembers one piece that Monroe sent to the gallery as part of a solo show. It was a moonlit scene featuring a mother bear and three cubs at the edge of a lake. Leshe fell in love with it and set it aside to purchase for herself when an important client noticed it and wanted to buy it. The gallerist couldn’t refuse, but she did commission Monroe to create a similar painting for her. “Lanford was working on a show for a major gallery in New York, so she had to put this one off but said she would have it for me by Christmas. She died in July. I keep thinking about that painting — and about Lanford, as a friend and talented artist.”

While most of her work was landscape painting incorporating wildlife, Monroe was also a bronze sculptor, although she didn’t have a chance to fully develop that aspect of her art. Horses were a significant part of her life — she and Thompson had several at their Taos home — and they were the primary focus of her sculpture.

In the late 1980s, when the couple first met, she was living near Thompson’s hometown of Athens, Alabama. He and his father and uncle were building a log cabin not far from Monroe’s house, and she would ride her horse over to watch the progress. They gradually got to know each other and fell in love. At the time, she had cast three equine pieces with a local foundry, but after the foundry went out of business, she turned her focus to painting, first in watercolor and then oils.

Rain Soaked Field, Limestone, Colorado | Oil on Board | 12 x 16 inches | Private Collection

Not long before she died, Monroe had begun creating a set of bronze chess pieces with wild animals taking on the various roles. The only one she finished sculpting was the chess queen — a mountain lion. After her passing, her friend and noted sculptor Sandy Scott, who had encouraged and helped her get back into sculpture, had the mountain lion cast. Pieces from the limited edition were presented as gifts to artists selected to participate in the Lanford Monroe Memorial Artist in Residence Program at the National Museum of Wildlife Art, a program Thompson and others helped establish in celebration of her “extraordinary contributions to wildlife art.” The program took place at the museum each summer for 11 years.

Monroe had also given Scott a casting of a beautiful mare, which Scott later gifted to Brookgreen Gardens, a sculpture garden and wildlife preserve in South Carolina. “Lanford would be delighted to know her sculpture now resides in an acclaimed American museum in her beloved South,” she says.

Having watched his wife’s art evolve over the years, Thompson saw her later paintings, especially of equine subjects, becoming more impressionistic and often incorporating what for Monroe were vivid hues. At the same time, she was moving toward more of a storytelling approach in some pieces. Veteran’s Day was inspired by an overgrown cemetery in rural Pennsylvania, where the brightness of small American flags contrasted with the quiet, overcast day. In the distance, a group of fox hunters is riding away, while in the cemetery in the foreground sits the “veteran,” the fox who got away.

Overlook | Oil on Board | 18 x 24 inches | Private Collection

Hajic also took note of Monroe’s talent as it grew and evolved. “She loved what she was doing,” the gallerist says. “I think had she lived, she would have been very successful.”

Following Monroe’s death, her husband, himself an artist, musician, and writer, spent several years gathering material and talking with her family and friends while writing a book on her life. Homefields: The Art of Lanford Monroe was published in 2008. As much as the beauty of her art, he says, her full-hearted approach to painting and life remains with him as an inspiration. “She made me realize that whatever I did in life, if I didn’t live it, breathe it, and love it, then maybe I’d better rethink my plans.”

No Comments