08 May Perspective: Breaking the Prairie

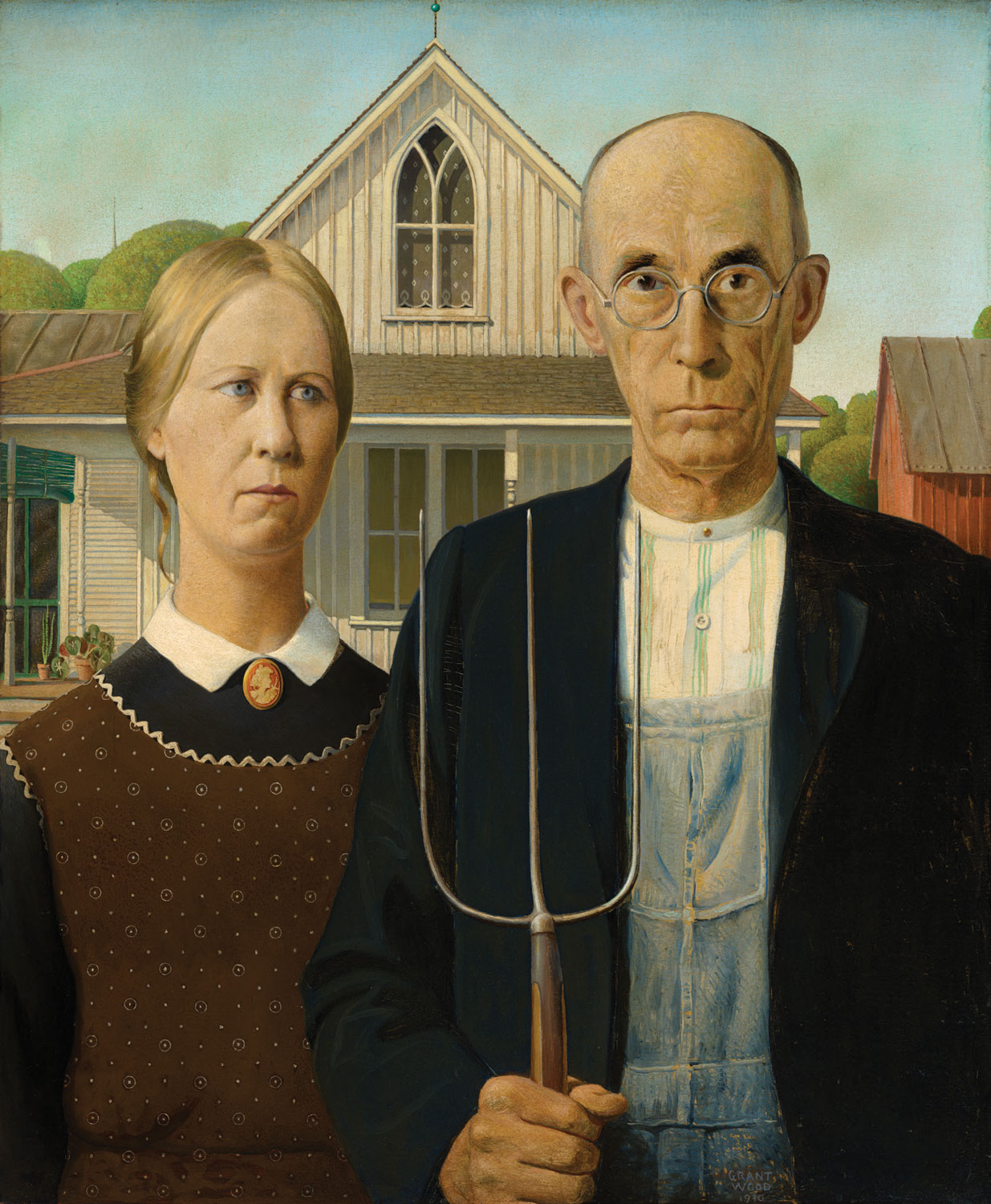

The pitchfork is what many people notice first, its tines sharp and unforgiving, its handle rigid in the farmer’s grip. His eyes stare coolly, and his mouth is set in moral rectitude — or is it half-concealed levity? The woman by his side (His wife? His daughter?) looks askance as if to say, “Are the tines of this fork for skewering sinners or for making hay?” Behind them, a Gothic window in a board-and-batten farmhouse overlooks the scene disapprovingly. Or does it endorse what in a certain light might be a tableau of erotic frankness? We do not know. As with much of Grant Wood’s painting, the effect is ambiguous.

Walter Wanger Productions | Grant Wood | 1940 | Gelatin Silver Print | Photo by Ned Scott Courtesy of the Figge Art Museum, City of Davenport Art Collection, Grant Wood Archive, Friends of Art Acquisition Fund, SB-4

The artist discovered the Iowa farmhouse portrayed in American Gothic 117 miles from Cedar Rapids, a city where he lived and worked for much of his life. He first sketched it on an envelope, then painted the scene on composition board. The oil won the Art Institute of Chicago’s bronze medal for painting in 1930 and brought Wood fame, linking him to a corn-fed, regionalist tradition of Midwestern art that included works by Thomas Hart Benton and John Steuart Curry.

The corn-fed label was misapplied, as suggested by a recent exhibit of his work at New York’s Whitney Museum, for Wood was every bit the modernist. As Barbara Haskell wrote for the exhibit’s catalog, “Like [Edward] Hopper, Wood portrayed the solitude and alienation of contemporary experience. By fusing meticulously observed reality with imagined memories of childhood, he crafted unsettling images of estrangement and apprehension that pictorially manifest the disquiet of modern life.”

Wood’s childhood had been troubled. Born on an Anamosa, Iowa, farm in 1891, he was a chubby, unathletic boy whom his Quaker father, Maryville, disparaged for his dreaminess. Maryville died when Grant was 10, and his mother, Hattie, uprooted the family from its rural home to the relative urbanity of Cedar Rapids. Wood may have seen that move as an attempt by his mother to diminish his father’s legacy. The effort failed. As Grant later noted, “To me, he was the most dignified and majestic of persons … There was a certain mystery and loneliness about [him] that I sensed even as a child — a strange quality of detachment which no one would ever be able to understand.”

As if in defense of his father’s agrarianism, Wood would later compose a career-changing essay titled “Revolt Against the City.” It railed against the cosmopolitan values of New York City and Paris (where he had studied during the 1920s), and championed rural ones. “One of the most significant things in the art world today,” he wrote, “is the increasing importance of real American art. I mean an art which really springs from American soil.” The emphasis upon “real” versus “fake” in his communications has contemporary resonance. And, as Haskell observed, “The social and political climate in which Wood’s art flourished bears certain striking similarities to America today, as national identity and the tension between urban and rural areas reemerge as polarizing issues in a country facing the consequences of globalization and the technological revolution. Yet, … its enduring power lies in its mesmerizing psychological dimension.”

Grant Wood | American Gothic | 1930 | Oil on Composition Board | 30.75 x 25.75 inches | Art Institute of Chicago; Friends of American Art Collection 1930.934. All rights reserved Wood Graham Beneficiaries / VAGA at Artists Rights Society (ARS), NY. Photograph courtesy Art Institute of Chicago/Art Resource, NY.

Wood believed art to be personal; a good painter depicted their crucial life struggles. It was “the depth and intensity of an artist’s experience that are the first importance,” he wrote. Great art starts “by looking inside ourselves, selecting our most genuine emotions.” He felt that “we’re conditioned in the first 12 years of our lives … everything we experience later is tied up with those 12 years.”

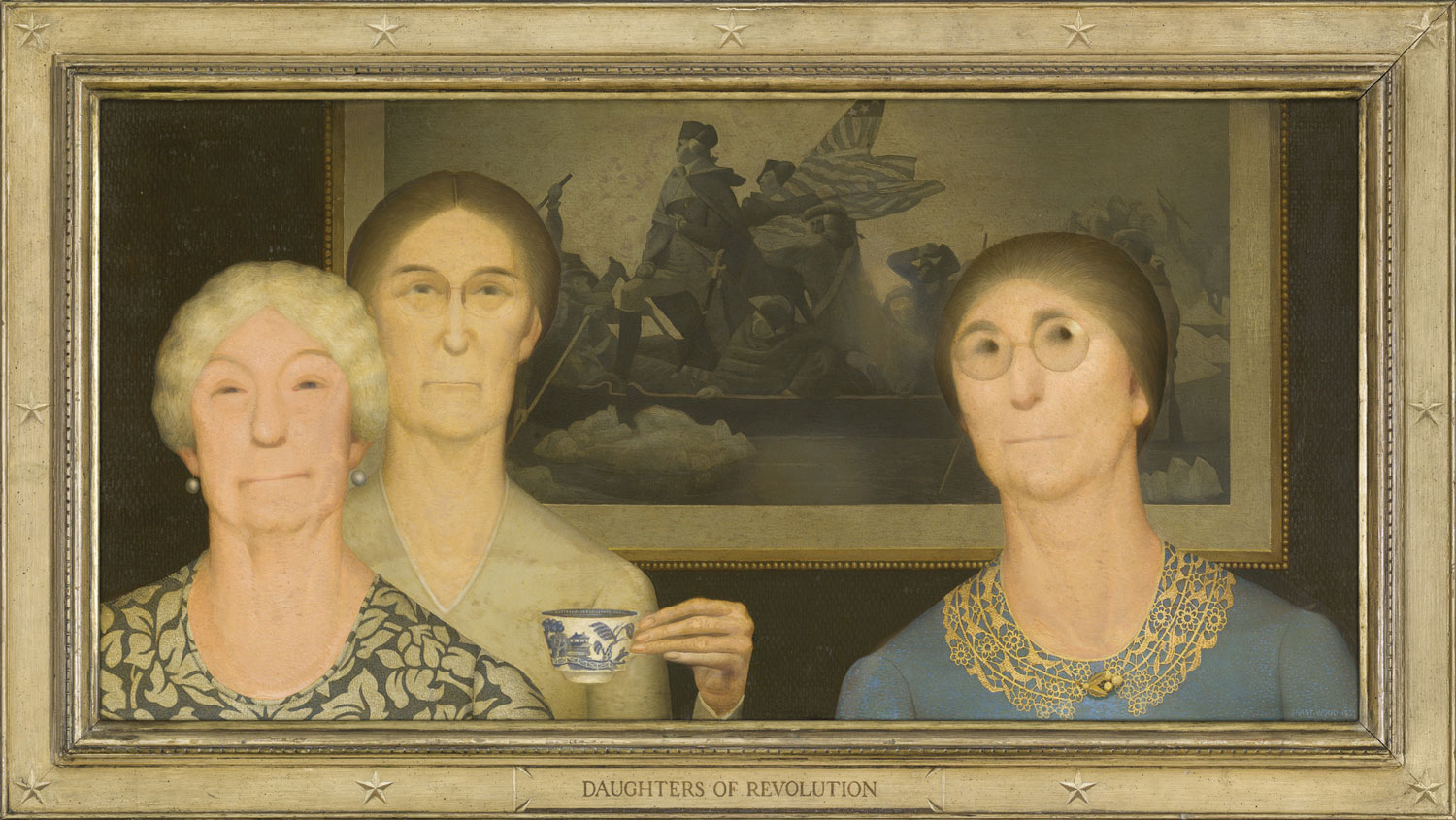

Two paintings implying the conflict between his father’s affection for the farm and his mother’s for the city are Spring Turning (1936) and Daughters of Revolution (1932). Wood was familiar with Freudian psychology, and in the former canvas, Iowa’s fields are inflated and rendered as presumably part of the male anatomy. Conversely, in Daughters of Revolution and Victorian Survival (1931), women are portrayed as austere townsfolk, physically dry and without sensuality — though his portrait of his mother, Woman with Plants (1929), plays her remoteness as maternally nurturing.

Wood reputedly was homosexual; the Whitney catalogue makes much of his painterly allusions to gay desire. His oil, Arnold Comes of Age (1930), shows a plaintive young man posed before a distant body of water where nude men romp. At the Iowa State Fair, the work won first place in portraiture and a grand prize in painting. Allusions to same-sex attraction would also be hinted at in Appraisal (1931), where a farm woman holding a Plymouth Rock chicken gazes flirtatiously at a wealthier, more urbane female customer. But a more controversial work would be Sultry Night (1939), a painting and lithograph of a nude farmer bathing from a horse trough. That lithograph was deemed pornographic by the U.S. Postal Service, which refused to mail it to customers. This action solidified Wood’s antipathy to Victorianism and puzzled him. “In my boyhood,” he said, “no farms had tile and chromium bathrooms. After a long day in the dust of the fields, after the chores were done, we used to go down to the horse tank with a pail … we would dip up pails full and drench ourselves.” His subsequent allusions to same-sex attraction were not dampened.

Grant Wood | Daughters of Revolution | 1932 | Oil on Composition Board | 20 x 40 inches | Cincinnati Art Museum; The Edwin and Virginia Irwin Memorial 1959.46 © Figge Art Museum, successors to the Estate of Nan Wood Graham/VAGA at Artists Rights Society (ARS), NY

But Wood’s best work speaks less to gay themes than to a celebration of agrarian life — and to darkness at the heart of the American experience. After moving from Cedar Rapids to teach at the University of Iowa, in Iowa City, he drank heavily (a saloon keeper remembered Wood trading sketches for whiskey — up to two bottles a day), fought to keep academic employment, and would die at age 50 of pancreatic cancer. What he accomplished in various mediums (sculpture, painting, ceramics, stained glass, wrought iron, and interior design) was not only the imagery of his best-known paintings, American Gothic and The Midnight Ride of Paul Revere (1931), but a unique take on the tortured side of American consciousness. Wood himself was tortured. As a populist, he was denigrated for his middle-American values (critics during the 1930s considered them proto-fascist). And like the Midwestern writers, Sinclair Lewis and Hamlin Garland, he was vilified for his recognition of the hypocrisy of small-town life, and for being unafraid to skewer it.

Wood’s view of that life’s white-picket-fenced and corn-fed simplicity, undergirded by repressiveness, is David Lynchian in tone. As with that filmmaker’s best work — Blue Velvet or Twin Peaks — a malignancy lurks beneath Wood’s perfect flower beds and lawns. The painting Spring in Town (1941) is case in point. In its foreground, a shirtless man spades a garden as a woman hangs a quilt and a child bends a limb of flowering dogwood. The house and church behind it are perfect, but the eye is drawn to the soil of the man’s garden. In its turning, darkness is unveiled, a gloom that clouds the pristine day.

Wood is not thought of as a Western painter, yet his canvasses express prairie wistfulness and a proclivity for dreaminess that overlie a thinly veiled melancholy. Emily Braun wrote in her Whitney essay, “Cryptic Corn: Magic Realism and the Art of Grant Wood,” that his intentions may have been more surrealistic than precise. “Magic Realism, as its oxymoronic name suggests, evinces instability — not order or normalcy. Despite the style’s polished surfaces and the surfeit of detail, it signals its own lack of transparency, an ironic distance, and controlled ambiguity,” she writes.

Braun compares Wood’s work to that of Henry Rousseau and to Giorgio de Chirico’s Italian metaphysical painting. She mentions the snake plant, which appears in Wood’s Woman with Plants, as a possible derivative from Giorgio Morandi’s 1917 painting Cactus, the plant “weirdly obdurate.” Braun writes: “Did [Wood] know it was commonly referred to as ‘mother-in-law’s tongue?’” It appears again “creepily on the porch of American Gothic.”

Grant Wood | Spring in Town | 1941 | Oil on Wood | 26 x 24.5 inches | Swope Art Museum, Terre Haute, Indiana 1941.30. © Figge Art Museum, successors to the Estate of Nan Wood Graham/VAGA at Artists Rights Society (ARS), NY

That painting is the work by which Wood’s legacy will be judged. As Peter Schjeldahl observed in his New Yorker review of the Whitney show, “American Gothic is, by a very wide margin, his most effective picture — though not his best, for which I nominate Dinner for Threshers (1934), a long, low, cutaway view of a farmhouse at harvest time.”

In Dinner for Threshers, Wood retreats to his pre-adolescent fixations: the male figures are wraithlike, the women automatons. The painter, Barbara Haskell wrote, appears here and elsewhere to be “molding the eternal world into a portrait of his inner self [which] involved tapping into what Hopper called the ‘intense, formless, inconsistent souvenirs of early youth.’”

At the end of his life, Wood — harried for his midland regionalism, dismissed by New York critics as irrelevant, vilified for what was seen as his reactionary aesthetics, weary from his battles in academia, and seriously ill — returned to his depictions of farm versus town. In 1941, Spring in the Country and Spring in Town existed only as drawings, but Wood hurriedly transformed them to the multi-colored oils that would be his last major works. Each was a testament to his parents’ different lifestyles. From his hospital bed, Wood pledged the greater loyalty to Maryville’s, promising his sister that “In the year ahead, I’m going to do the best work of my life. My first painting will be a portrait of our father.”

A month before Wood’s death, Thomas Hart Benton visited him in the hospital and reported that “when he got well he was going to change his name, go where nobody knew him, and start all over again with a new style of painting.” One can only speculate what that style might have been. In February 1941, Wood died, his body traveling home — first to David Turner’s mortuary in Cedar Rapids, behind which the artist had lived for 10 years with his mother, and then to Anamosa, where he lies next to Hattie in the family plot.

No Comments