17 Dec Perspective: Charles Schreyvogel [1861–1912]

He had a city boy’s fascination with the West. And though he’d often visited and was influenced by explorer-artists such as George Catlin and Thomas Moran, he painted not on the dry prairie or desert plain but on the flat roof of a Hoboken, New Jersey, brownstone. He’d seen Montana, but his Rockies were not the Big Horns or Absarokas, but the bluffs of New Jersey’s Palisades. And though he’d befriended military, the costumed trooper before him was not a veteran but a teenage athlete from Hoboken’s Stevens Institute. The gangs he recollected were less those of Jesse James or Butch Cassidy than the Bowery Boys of Manhattan. He was Charles Schreyvogel [1861–1912], the son of a German immigrant from the Lower East Side, and an artist who came to rival Frederic Remington in reputation if not in output.

At Remington’s death in 1909, the popular publication Leslie’s Weekly called Schreyvogel “America’s greatest living interpreter of the Old West.” It added, “He is more than a historian … he is giving us an invaluable record of those parlous days of the western frontier, when a handful of brave men blazed the path for civilization and extended the boundaries of empire for a growing nation.” And a curator at the Metropolitan Museum of Art would note that, “Schreyvogel helped to engineer the concept of the cowboy and the cavalryman as icons of American masculinity.” He championed soldiers of the American Indian Wars and painted portraits of Native Americans judiciously. But his legacy would not be without controversy. He and other artists of his period would be criticized by Stanford historian Alex Nemerov for having demonstrated anti-immigrant, even racist tendencies. Anglo-Saxon founders were “native” Americans and “Indians” were heathens at the gate, represented at New York’s Ellis Island by a 19th-century influx of European aliens.

Nemerov would argue in an essay titled “Doing the ‘Old America’,” in the 1991 collection The West as America: Reinterpreting Images of the Frontier, that “the iconography of cowboys and Indians that arose so vigorously around the turn of the century is best understood in relation to the urban, industrial culture in which this iconography was produced.”

Schreyvogel was nothing if not urban. And New York, according to Nemerov, was under siege by immigrants. Schreyvogel’s father had owned a candy store near Avenue B, and though the family was first-generation German-American, they fled the Lower East Side because of the overflow of tough Irish and Italian hooligans from the gang-ridden Five Points neighborhood.

The Schreyvogels were decidedly middle class; a neighbor later described Charles as “[a] gentleman, full of old-world courtesies.” To escape the gangster hordes, his father, during the 1870s, moved his family to then-rural Hoboken, which had a polite German population and a small-town charm. Charles roamed its fields and scrambled up its cliffs, quickly seeing New Jersey as a surrogate for the West. It was as if he anticipated Saul Steinberg’s 1976 New Yorker cover, View of the World from Ninth Avenue, suggesting the frontier began at the Hudson.

He’d worked as a goldsmith’s and a lithographer’s apprentice and studied with the painter Carl von Marr in Germany. But his fiercest teachers would be the Western novelists, cowboy filmmakers and Wild West impresarios of the day. He met Buffalo Bill in New York and spent hours sketching the horses, cowboy and Native American performers of his show.

As had former president Theodore Roosevelt, Schreyvogel first visited the West’s dry climate for his health — as antidote to his asthma and depression — and secondarily to draw. In 1903, he returned from five months spent sketching Native Americans and troopers around Colorado’s Ute reservation, “his face dark as old leather,” writes James D. Horan in his book, The Life and Art of Charles Schreyvogel, “and his health improved.” He carried his sketches to his Hoboken rooftop and began painting.

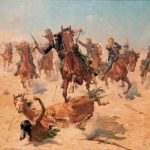

Success did not come quickly, but in 1900, when a canvas titled My Bunkie (depicting a trooper rescuing an unhorsed bunkmate from a Native American onslaught) won the Thomas B. Clarke Prize at the Academy of Design in New York, Schreyvogel caught the eye of critics and fellow painters, including Remington, who recognized him as a competitor. Remington may also have disliked Schreyvogel for his immigrant heritage. As the artist fumed in a letter to Poultney Bigelow, editor of Outing magazine, “Jews — Injuns — Chinamen — Italians — Huns, the rubbish of the earth I hate.” The anger he would unleash toward Schreyvogel — a “Hun,” as Germans were called — would be unprecedented in American artistic feuds.

Schreyvogel had traveled West between 1893 through the early 1900s, and “Custer fascinated him,” Horan writes, particularly his campaign of 1868 to 1869 against the Southwestern Plains tribes. “Etched in Schreyvogel’s mind was the story of Custer’s order that Santana, the Kiowa, and the other chiefs surrender and return to [Oklahoma’s] Fort Cobb.” It had been a dramatic standoff, and during the winter of 1902, Schreyvogel began painting it.

The resulting Custer’s Demand was completed in 1903. It showed Custer, accompanied by officers, on a winter plain entreating his Native American counterparts to leave the field. Horan writes, “Schreyvogel, as always, had first done extensive research to make sure that the scene was historically correct: horses, the costumes of the men — red and white — and their equipment, even to the thickness of the stirrup leathers.” The painting was shown at New York’s Knoedler Galleries and was “an immediate success.” Horan adds that Schreyvogel told his wife, Lulu, “I think it is the best thing I have ever done.”

Then the New York Herald reproduced the painting, accompanied by a four-column interview with its creator and a photograph of him in a derby, painting on the Hoboken rooftop. Remington was incensed. He wrote to the Herald, “While I do not want to interfere with Mr. Schreyvogel’s hallucinations, I do object to his half-baked stuff being considered seriously as history.” He disputed the size of Custer’s horse, the color of his trousers, the stirrup cups employed and other of the painting’s details.

As both men were icons of Western painting, the comments produced a national controversy, according to Horan. Custer’s widow and an officer present attested to the canvas’ accuracy, and even President Roosevelt (a former rancher and a symbol of the new West) chimed in. As recorded in Horan’s book, during a White House visit Roosevelt told Schreyvogel, “What a fool my friend Remington made of himself, in his newspaper attack, he made a perfect jack of himself, to try to bring such small things out, and he was wrong anyway.”

It’s unclear as to why Remington resented Schreyvogel. Remington was at the height of his fame; Schreyvogel was just attaining his. Remington admitted, in a letter to a friend, (Colonel Schuyler Crosby, an officer depicted in Custer’s Demand) that “I despise Schreyvogel.” Remington had wanted to paint Custer, and as Horan writes, “It was obvious that Remington was seething with jealously that he had a rival in the field.” And, “Schreyvogel, painting on a roof — of all places in Hoboken — may have been an affront to [his] view of a true [W]esterner.”

Schreyvogel, on the other hand, never criticized his accuser. He said simply, “He is the greatest of us all.”

Urbanity was Schreyvogel’s lot, and it worked in his favor. His canvases, largely of military personnel, were dramatic without being romantic. And their frantic activity — troopers pursuing Native Americans, Native Americans being slain by troopers — anticipated the frenzy of the new century’s comic books, Western films and television shows. As Horan writes, “The viewer could almost hear the thunder of the horses, the wild, shrilling cries of the warriors, the crack of the Winchesters, the thud of saber steel on bone, and the scream of wounded horses.” A majority of these paintings reinforced the belief that Native Americans were violent savages whose extermination, or removal, was crucial to Manifest Destiny.

A siege posture in Schreyvogel’s paintings supports Nemerov’s thesis that his “last stand” pictures were unconscious allegories of immigrant intrusion. Defending the Stockade (circa 1905) is a case in point. It shows a bevy of wounded troopers, besieged by American Indians, hurrying “to close the fort’s gates to the enemy,” Nemerov writes. He argues this may represent “an Anglo-Saxon race in a world ‘overrun’ with immigrants. … If Schreyvogel made ‘closing the door’ his central theme, he did so because the terms he possessed for representing the West emerged from a culture in which the idea of closing the door, of enacting anti-immigration legislation, was important.”

Well, perhaps. Schreyvogel himself was of immigrant stock, and he venerated the American Indians he met on his trips, complaining that they were treated miserably. “The conditions on the reservations never failed to appall him,” Horan writes. “He spent hours describing to Lulu the poverty of the tribes,” and how the Indian Bureau had failed them. His daughter remembered that “he would sound very bitter when he talked about the terrible conditions on the reservations. Particularly the children. He would give them every penny he had.”

His sympathy was emphasized in a 1901 canvas titled How Kola. It shows a mounted trooper vaulting toward a fallen Native American, then holding fire when the Native American shouts “how kola,” or “stop friend.” The scene was based on an incident from an 1870s, hand-to-hand skirmish with the Sioux. A trooper had been saved by a tribe member from freezing to death in a blizzard, and when later he recognized that man in combat, his life was spared. Along with My Bunkie, it became one of Schreyvogel’s most popular paintings.

His family bought a Catskills farm in 1905 and spent their final summers there. Schreyvogel’s paintings acquired a ruminative tone, his impasto thick and his subject matter rural. He never ceased painting the West, however, with his signature motifs: “The vivid, remote, startling blue sky,” Horan writes, “the stark yellow light of the plains, the crystal clear air, the brown barren earth, the rearing nervous horses ready to plunge from the canvas, and the fighting men, white and red.” Schreyvogel lamented that “the last of the frontier was gone,” and in Hoboken, painting on his rooftop studio, Horan adds, “he daily turned his back on one of the most striking views in the world, New York’s rising skyline, to face the somber, rocky face of the lower Palisades.”

Schreyvogel died — a victim of septicemia — in January 1912. He left perhaps 100 paintings, numerous sketches and a few bronzes. His rival, Remington, had left some 2,500 works. Yet recently a Schreyvogel oil, Dispatch Bearers, sold at Christie’s for $245,000, and in 2015 a watercolor, Mountain Man, sold at Sotheby’s for $6,250. A bronze, The Last Drop, in 2007 sold there for $108,000. The National Cowboy and Western Heritage Museum in Oklahoma City, Oklahoma, the Sid Richardson Museum in Fort Worth, Texas, and the Gilcrease Museum in Tulsa, Oklahoma, hold the majority of his paintings.

What Walt Whitman said of Thomas Eakins seems a fitting epitaph for Schreyvogel. And it’s a sentence Remington might have muttered of his adversary: “[He] is not a painter, he is a force.”

- Charles Schreyvogel painting on his studio rooftop in New Jersey, ca. 1903. Charles Schreyvogel Collection, 1969.197.19.13. Donald C. & Elizabeth M. Dickinson Research Center, National Cowboy & Western Heritage Museum, Oklahoma City, Oklahoma.

- “My Bunkie” | Oil on Canvas | 25.2 x 34 inches | 1899 | Metropolian Museum of Art, gift of friends of the artist, by subscription, 1912

- “How Kola” | Oil on Canvas | 25 x 35 inches | 1901 | On loan to the Buffalo Bill Center of the West, Cody, Wyoming, from a private collection

No Comments