10 Jan Perspective: Conversations between Past and Present

If a picture says a thousand words, then Hopi potter Nampeyo [c. 1859 – 1942] has shared many great tales. Widely known as the most remarkable Pueblo potter of all time, Nampeyo was a prolific artist, and her legacy upholds its place in the world of American fine art.

Nampeyo did not speak English, nor did she personally sign her work. She is the subject of many books, scholarly discussions, and ongoing teachings, although details vary throughout the widespread accounts. Pottery attributed to Nampeyo can fetch well into the six-figure range, with collectors vying for her pieces worldwide.

Attributed to Nampeyo, Bowl | Pottery and Paint | c. 1920 | National Museum of the American Indian, Smithsonian | institution (22/1757). Photo by NMAI Photo Services

The success and longevity of her work reflect her artistic skills and astute business acumen. What she accomplished at a time when Indigenous peoples were viewed as subordinate rather than leading artists is a tribute to her extraordinary talent, creativity, and foresight.

“To only see Nampeyo as a potter is to ignore her important roles within her society as Clan Mother, a participant in the ceremonial life of her village, a caregiver, a wife of a farmer, and other roles,” says Diane Dittemore, Associate Curator of Ethnology at the University of Arizona’s Arizona State Museum.

Arnold Genthe, Nampeyo | Gelatin Silver Print | 9.5 x 7.563 inches | c. 1926 | NPG.98.51 | National Portrait Gallery, Smithsonian Institute

Born in Hano, on First Mesa in Arizona, around 1859, she was the eldest of four children to her mother, White Corn (Tewa, Corn Clan) and her father, Quootsva (Hopi, Snake Clan at Walpi). Her arrival came at a tumultuous time in history. The Mexican-American War had ended 10 years prior, annexing the Southwest region to the U.S. Indigenous peoples were being forced from their lands, stripped of their cultural traditions, and pushed onto reservations. At the same time, tourism in the Southwest had begun bringing visitors from the East Coast and Midwest through newly expanded railroads. It would become a silver lining in desperate times for many Hopi-Tewa.

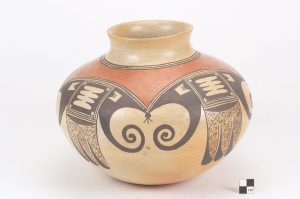

Nampeyo, Tile | Pottery and Paint | c. 1900 | National Museum of the American Indian, Smithsonian Institution (5/8166). Photo by NMAI Photo Services

Taught by her paternal grandmother, Nampeyo was a master potter by the time she reached her mid-teens. She kept house for her brother, Tom Polacca, who provided food and lodging for the 1875 Hayden Survey, which mapped out the Four Corners area. As a result, she was exposed to white settlers, including William Henry Jackson, a photographer believed to have documented the first image of Nampeyo.

“Nampeyo had an incredible spark of creativity and really ran with it,” Dittemore says. “A lot of people were not engaging with the outside world in the same way Nampeyo’s family did.”

Nampeyo’s work, along with that of her neighbors, was sold in the first trading post at the villages of First Mesa by Thomas Kern in 1875. It was said the Walpi were hugely critical of Nampeyo and those she taught, and as a result, Nampeyo began to look further afield for materials and inspiration beyond the traditional Hopi teachings she received.

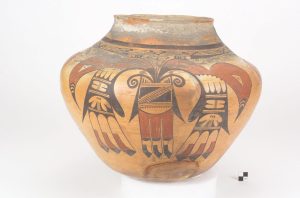

Nampeyo, Jar/Olla | Pottery and Paint | c. 1925 | National Museum of the American Indian, Smithsonian Institution (17/6133). Photo by NMAI Photo Services

She did not need to look far. Below First Mesa are the ruins of Sikyatki, an abandoned village from the 1500s. Fragments of Sikyatki Polychrome pottery remained scattered across the site.

Identified as Ancestral Hopi yellow ware, Sikyatki Polychrome is distinct for its creamy yellow color and high sheen. Low, wide vessels are painted with detailed depictions of life forms such as animals and plants. As culture dictates, each piece has a living spirit and carries a prayer from its maker. References to clouds and rain are often depicted as a way of asking for rain to nourish crops.

Nampeyo took inspiration from what she found and would go on to create her own designs, which became known as Sikyatki Revival.

Nampeyo, Jar | Pottery and Paint | 1920-1940 | National Museum of the American Indian, Smithsonian Institution (21/4629). Photo by NMAI Photo Services

In 1895, an excavation of Sikyatki was led by Jesse Walter Fewkes of the Smithsonian Institution. Nampeyo’s second husband, Lesso, along with other men from the village, were hired to work on the site. In later years, Fewkes would argue that he played a pivotal role in Nampeyo’s success, crediting himself as the person who introduced her to Sikyakti pottery. “Fewkes wanted to take credit for the proliferation of the Sikyatki pottery revival, but Nampeyo had already been incorporating it,” Dittemore says.

Nampeyo would have taken the iron-rich clay in rock form from the area and ground it until it could be mixed with water, hand-coiled, painted, fired in coal fragments and sheep manure, then polished. Unlike others who sketched their work, Nampeyo decorated the pots free hand, typically painting in one long swoop of her handmade yucca paintbrush dipped in pigments derived from the earth. The apparent ease with which she completed her depictions remains a source of identification for her works.

Nampeyo, Jar | Pottery and Paint | 1910-1920 | National Museum of the American Indian, Smithsonian Institution (18/7532). Photo by NMAI Photo Services

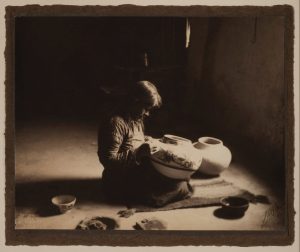

By the 1900s, Nampeyo had become a household name, with her image appearing in tourist publications. Edward S. Curtis was among the photographers to capture her on camera, making her an icon of Hopi culture at a time when other Indigenous peoples faced destitution.

In 1905 and 1907, Nampeyo and her family were invited to live for three-month stints at Hopi House in the Grand Canyon, where she would demonstrate her skills as a potter and sell her work to tourists. She was invited to demonstrate in expositions, and her work was featured at World Fairs.

“America, in terms of artistic culture, was the backwater of the world,” says Gerald Clarke, a professor of ethnic studies at the University of California, Riverside. “People wanted to claim historic cultures and traditions as their own to match those of Europe.”

By the 1920s, Nampeyo’s eyesight began to fail. Although she could still hand coil the seed jars and the saucer shape vessels she was known for, she relied on family members to paint her balanced designs in the classic red, blacks, and whites.

Edward Curtis, The Potter — Nampeyo | Platinum Photograph | 5.8125 x 7.4375 inches | Date Unknown | Peterson Family Collection | Courtesy of Western Spirit: Scottsdale’s Museum of the West

Her daughter Fannie and granddaughter Dextra are thought to have been the most talented contributors to this effort. Dextra’s nephew Les Namingha is one of the voices in an upcoming catalogue titled Native American Art from the Thomas W. Weisel Family Collection, which will be released this spring by the Fine Arts Museums of San Francisco. The catalogue includes the voices of 90 authors who share valuable insights behind the creation of more than 200 pieces of Indigenous art, collected over decades by philanthropist Thomas W. Weisel, including pottery by Nampeyo. The mammoth endeavor sparked dialogue and partnerships between Indigenous peoples and the museum, a movement that is being mirrored by other institutions across the U.S.

It also served as the impetus for a current exhibition at San Francisco’s de Young Museum titled Nampeyo and the Sikyatki Revival, which opened in February 2021. Each of the 32 pieces on display was handpicked from the museum’s collection, and the pottery on view spans six centuries from the 1400s to the present day. “While small, it is a mighty show,” says Hillary Olcott, the exhibit’s co-curator with Hopi potter Bobby Silas, and the associate curator of the Arts of the Americas for the Fine Arts Museums, San Francisco.

Nampeyo, Jar | Pottery and Paint | 1920-1940 | National Museum of the American Indian, Smithsonian Institution (21/3256). Photo by NMAI Photo Services

Visitors can gage the spectrum of Nampeyo’s life works from her inspiration in Ancestral Hopi yellow ware, to the legacy she left, apparent in the works by four generations of her descendants, who maintain the cultural practices of Hopi and Hopi-Tewa.

“Against a backdrop of Pueblo cultural practices where individuals were not encouraged to assert their individuality, she emerged from anonymity,” Dittemore says. Nampeyo paved a pathway few deemed possible. Her legacy is now part of a new narrative of Indigenous voices telling their own cultural stories beyond those of assumed accounts and museum interpretations.

Suzi Mitchell is a Scottish freelance writer who lives in Colorado with her three children, a spoiled dog, and a nonchalant cat. When not writing about artisans and architecture for publications on both sides of the Atlantic, she paints.

No Comments