12 May Perspective: Of Birds and Texas

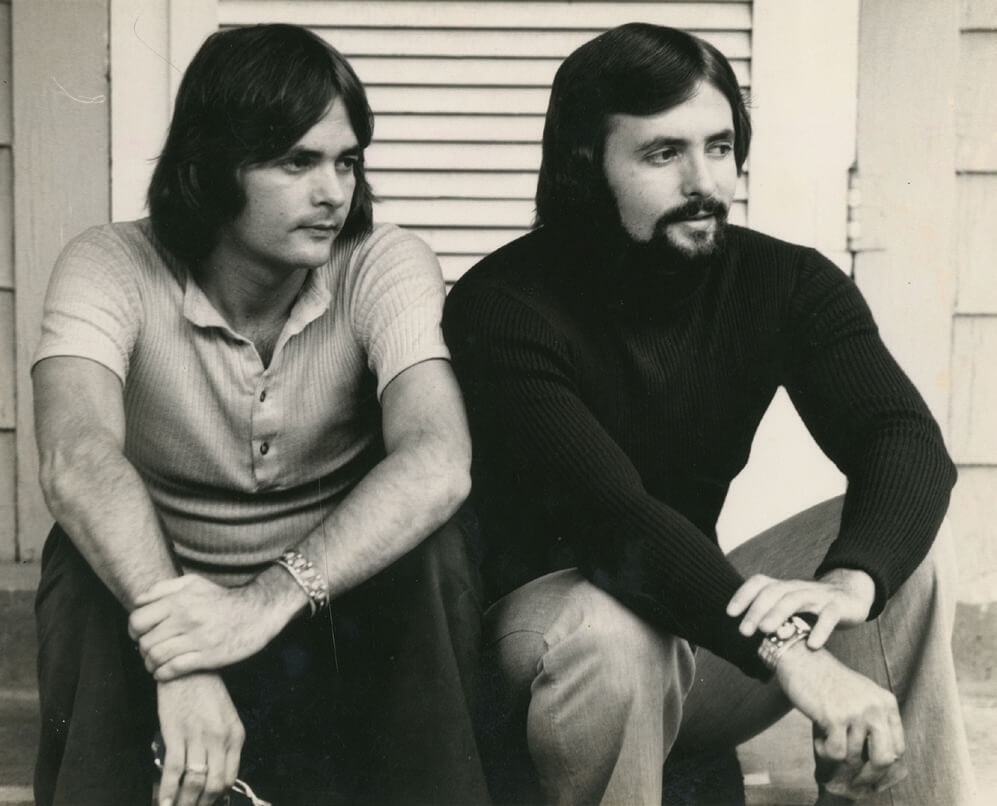

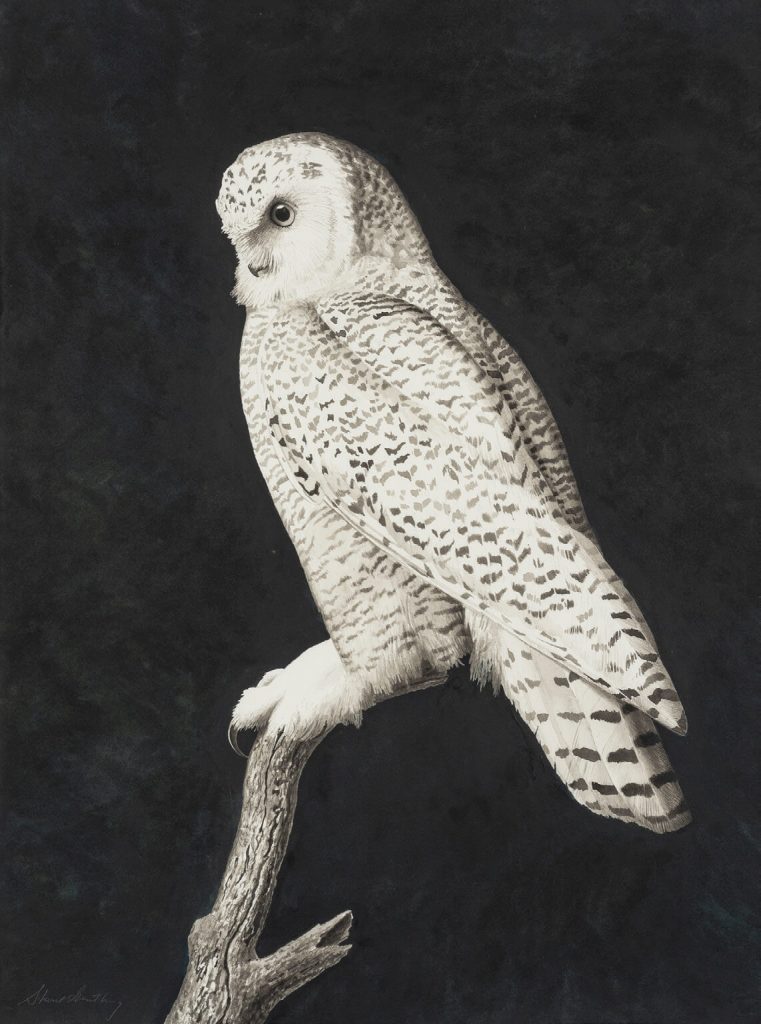

When Texas-based artists and twin brothers Stuart and Scott Gentling were asked why they never tried to extend their art presence and collector base beyond their home state, they always responded, “Because we don’t need to.” And it was true. Wealthy collectors and patrons in Fort Worth and other regions of the Lone Star State bought virtually everything the duo painted. Commissions for official portraits came in for such figures as the former Governor and President George W. Bush, the late Amon Carter Sr. (owner and publisher of the Fort Worth Star-Telegram), and primatologist Jane Goodall. Of Birds and Texas, the brothers’ masterpiece, is a boxed portfolio of 50 paintings of birds and landscapes, an homage to John James Audubon, that sold for $2,500 per copy and earned high acclaim.

But it wasn’t just the Gentlings’ exceptional talent — painting separately or both having a hand in the same artwork — that caught the eye of collectors and dealers. The brothers found themselves to be the center of attention beginning in boyhood. Those around them, including many who went on to become renowned in various fields, were magnetized by Scott and Stuart’s insatiable curiosity, big ideas, eclectic and often-obsessive interests, and nonstop creativity.

“High caliber, interesting people were drawn to them from a young age,” says Jonathan Frembling, Gentling Curator and Head Museum Archivist at the Amon Carter Museum of American Art in Fort Worth. In a sense, Frembling says, the brothers carried on the custom of earlier Fort Worth artist circles and salons in a community historically known to delight in its eccentric, homegrown talent.

While the Gentlings never sought out broad recognition during their lifetimes, Scott’s death in 2011 (Stuart died in 2006) initiated an effort to present their achievements and remarkable lives to the larger world. As executor for their estate, their sister Suzanne Gentling gifted the Amon Carter Museum with 60 boxes of manuscript materials and artifacts from the twins’ lives. The material became the core of the Gentling Study Center, which opened at the museum in 2019 and includes a dedicated curatorship as well as fellowships available to scholars for research on any artist within the museum’s archives.

The crowning touch in honoring the brothers is a comprehensive retrospective opening September 25 and continuing through January 9, 2022. Imagined Realism: Scott and Stuart Gentling features 160 artworks along with objects that represent some of their wildly varied interests, including Texas birds and landscapes, the ancient Aztec empire, and a lifelong pursuit of collecting rare items, including antique musical instruments and original historical clothing dating back to King George III.

“People will be astonished,” Fort Worth art historian Scott Barker says of the exhibition, adding that the Gentlings’ pursuits and artistic facility “makes you really marvel at what the human mind can do.” Barker was one of six scholars who contributed essays for a major monograph produced in conjunction with the show.

If anyone wondered what Stuart and Scott were up to as boys, one look around their shared bedroom would tell the tale. According to family members whose accounts about the brothers fueled many stories-turned-legends, their perpetually messy room was crowded with evidence of their fascination with nature and self-directed learning. There were live reptiles, insects, and birds. There were dead birds and small mammals the brothers had shot and which Stuart was using to practice taxidermy through a correspondence course. There were tumbling stacks of papers and books, including comic books set in the Aztec empire. There were model sailboats, a miniature railroad, and miscellaneous projects in every state of completion.

As adults, the Gentlings admired the model of the 19th-century gentleman naturalist, a hands-on, self-styled scholar eager to learn about the botanical and animal realms. As boys, they lived that model, roaming the semi-rural wooded bottomland by the Trinity River on Fort Worth’s west side. In the 1950s, when the world was enthralled with rocket ships, the brothers talked an uncle into giving them gunpowder, using it to build and fire several three-stage rockets. “It all goes great — until it doesn’t,” Frembling says. A malfunctioning rocket resulted in a massive shockwave explosion. A neighbor, Governor John Connally, rushed over, and the boys were taken to the hospital, singed and embarrassed, but okay. “They couldn’t just read about something,” Frembling says. “They wanted to build, to do.”

The Gentlings’ obsession with birds — and the initiation of their artistic teamwork — began as young teens when Stuart came across a copy of Audubon’s book Birds of America in the library of the Fort Worth Children’s Museum (now the Fort Worth Museum of Science and History). He later admitted to borrowing and never returning the tome, which he used to make a drawing based on a painting of wood ducks. Scott had begun teaching himself to paint with watercolors, and the two worked together on their first collaboration, a large-sized copy of Audubon’s wood ducks.

Following high school, the brothers enrolled in Tulane University in New Orleans. Scott dropped out after a year, returned to Fort Worth, and then entered the Pennsylvania Academy of the Fine Arts in Philadelphia. Stuart graduated from Tulane and briefly attended law school before joining Scott. They eventually settled back in Fort Worth with an art education but without a degree. Lifelong bachelors (although each had girlfriends over the years, one of whom unsuccessfully proposed to Stuart), the Gentlings lived together in Fort Worth for the rest of their lives.

With support from such high-end players as heiress and collector Anne Burnett Tandy, doors began opening for the Gentlings’ art. Tandy was instrumental in introducing Scott’s paintings to Donald Vogel, owner of Valley House Gallery in Dallas. After testing the market with Scott’s work in a group show in November 1965, Vogel gave the artist his first solo show the following March, with an accompanying catalogue. Kevin Vogel — the gallerist’s son and now co-owner of Valley House with his wife, Cheryl — remembers his father doing something at the opening that he’d never done before. After hanging the show, he closed off that part of the gallery so the enthusiastic crowd couldn’t see Scott’s work. Following a period of wine and schmoozing, Vogel opened the door for the big reveal. “People were blown away,” Kevin Vogel says. “There was a feeding frenzy, and it almost all sold out.” Valley House represented Scott for the next 10 years.

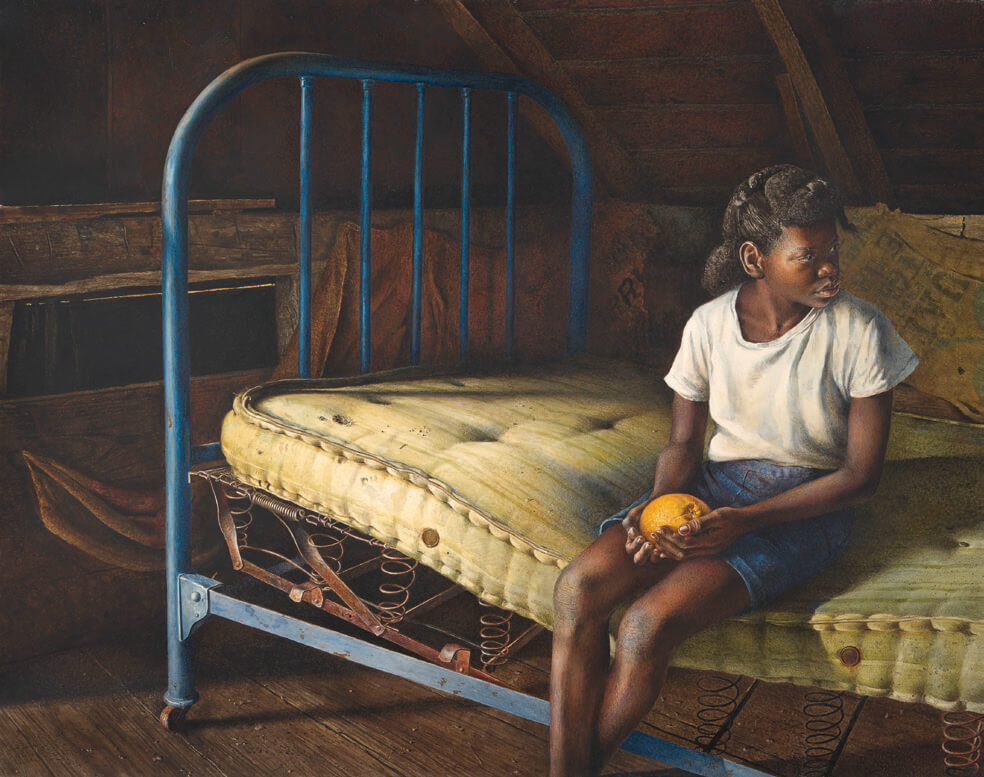

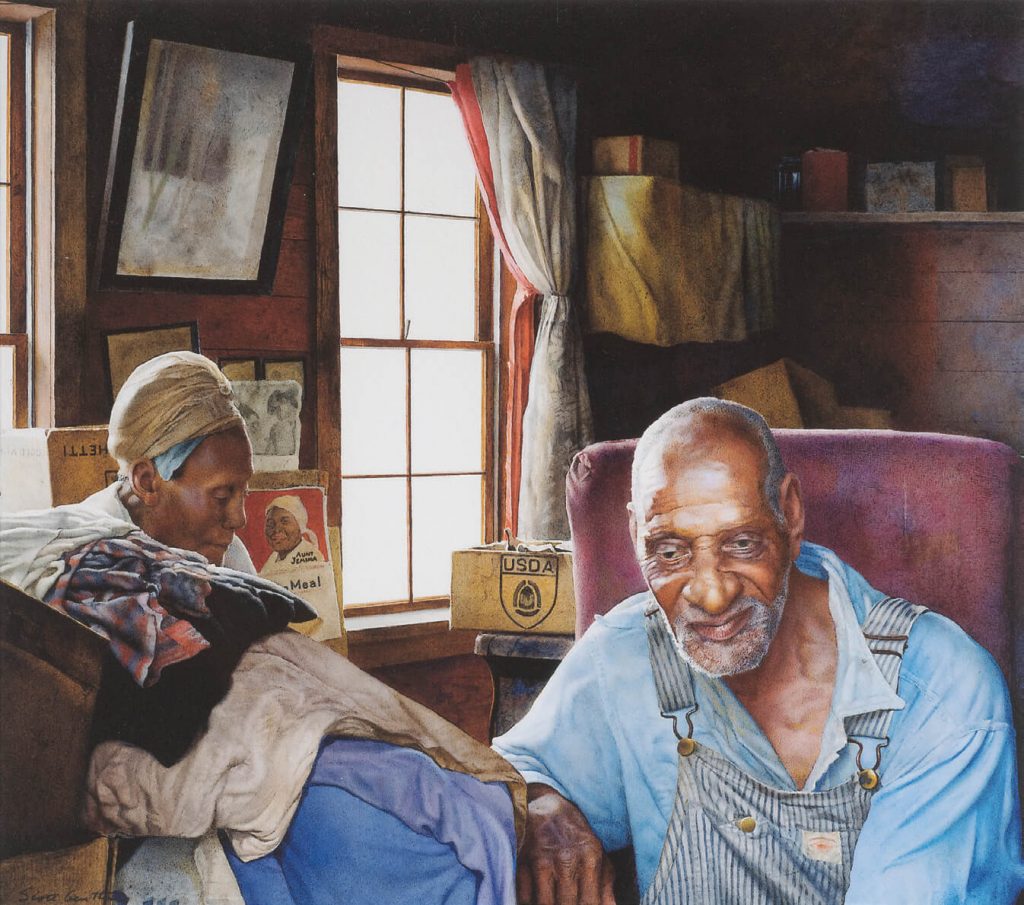

While the Gentling brothers employed similar painting styles, differences in the way they worked produced a synergistic whole. “Stuart impresses me as a top-tier representational painter,” Barker says. “Scott was a once-in-a-lifetime representational painter, a special breed, and those who knew him, knew that.” Working primarily in graphite and watercolor on paper throughout their careers, Scott’s style was meticulously detailed and exceptionally crisp. Stuart had an accomplished but looser approach, and an emotional intensity that worked well, for example, with clouds and backgrounds in their bird imagery.

Vogel speculates that Stuart may have contributed compositional elements and underpaintings while Scott came in with detail, although the artists are known to have gone back and forth with many aspects of their work. “Stuart credited Scott for the ‘extra touch’ he brought to every painting he worked on, and Scott trusted Stuart’s extraordinary eye for layout and composition,” Barker says. Some paintings were signed by one or the other and some by both. The brothers were prolific, producing hundreds of landscapes and still life paintings along with special projects.

Likewise, the Gentlings complemented each other in their interactions with the world. Stuart was the front man, chatty and social. He was the one who networked, cultivated patrons and collectors, and took care of the business end of things. Scott was more reclusive, rarely traveling aside from the brothers’ trips around the state to scout out birds or their research ventures in Mexico. Scott’s preference was to be at home painting, reading, and filling up sketchbooks and notebooks.

Together the pair achieved remarkable things that neither could have done alone. Like the bird book, which involved years of intensive effort: researching, sketching, and painting Texas birds; marketing; working with the printer and publisher; and raising funds, including mortgaging their home, their mother mortgaging hers, and the twins eventually selling a valuable original Audubon watercolor drawing (through Sotheby’s for $253,000) to meet the project’s enormous expenses.

Another labor of love was the Gentlings’ scholarship and artwork related to the Aztec empire just prior to Spanish conquest. The brothers spent decades pursuing their Aztec fascination, taking part in archeological digs in Mexico and studying historical works and eyewitness accounts from Spaniards en route to conquest. Stuart taught himself to read and speak the Aztec language of Nahuatl. Scott produced volumes of extraordinarily detailed ink drawings as visual interpretations of the Aztec capital city of Tenochtitlan in 1519. Large-scale prints of the drawings were compiled as a limited-edition boxed book, The One Reed Year: What It Might Have Felt Like to See Aztec Mexico on the Eve of Conquest. Scott also created intricate three-dimensional models of temples and other sacred spaces in Tenochtitlan.

“I love that they did what they wanted to do and went all the way with it. They never went halfway in anything. And both of them working together made a wonderful whole,” says Vogel. The Gentlings’ oeuvre can be seen as autobiographical, reflecting their particular, sometimes-quirky passions. At the same time, their creations and the brothers themselves were welcomed with an equivalent passion by the upper strata of Fort Worth society and admired by Texans of all ranks. “These guys were part of the tapestry of Texas art,” Frembling says. He adds that the enthusiasm he sees around the upcoming exhibition demonstrates “how deeply they were loved.”

No Comments