04 Jan Perspective: Poetically Inclined

Decades before the term “New Age” achieved popularity in American culture and long before a fascination with Eastern philosophies brought yoga and meditation into the Western consciousness, an intensely inward-looking American artist was tapping into mystical, non-material reality and creating exquisite, ephemeral paintings from her experiences. Agnes Pelton called these abstracted, delicately rendered images “Imaginative,” although they emerged not from mental activity, but from a place of deep stillness and quiet.

Ahmi in Egypt | Oil on Canvas | 36.19 x 24.19 inches | 1931 |Whitney Museum of American Art, New York; Purchased with funds from the Modern Painting and Sculpture Committee 96.175. ©Estate of Agnes Pelton

Although Pelton attained some recognition from the art world during her lifetime, notably as part of the landmark 1913 Armory Show and later with several solo museum exhibitions in California, she fell into almost total obscurity following World War II. She had removed herself geographically and otherwise from the East Coast art world and had no interest in self-promotion or renown. What mattered to her was creating authentic visual expressions of the radiance, beauty, and beneficence she perceived as underlying and continually forming the material world.

Fortunately, the art world is rediscovering Pelton. A traveling retrospective, Agnes Pelton: Poet of Nature, was organized by art historian and curator Michael Zakian and toured the country from 1995 through 1996. The exhibition showcased Pelton’s distinctive approach and repositioned her in the context of American Modernism. Her visual voice was unlike other Modernists of her era — and even unlike members of the New Mexico-based Transcendental Painting Group with which she was associated.

Artist Agnes Pelton, photographed by Alice Boughton | Date Unknown | Carolyn Tilton Cunningham Family Collection, courtesy of Nyna Dolby

In 2020, the Phoenix Art Museum produced another traveling exhibition, the first in more than 24 years. Curated by Gilbert Vicario, Agnes Pelton: Desert Transcendentalist consisted of abstract paintings and was exhibited at the Whitney Museum of American Art in New York City, among other venues. As Whitney curator Barbara Haskell puts it, when early American Modernism is discussed today, Pelton “is definitely part of the conversation.”

Pelton’s unusual, and in some ways traumatic, childhood likely set the stage for turning her naturally introspective character toward a non-conventional spiritual path and the desire to paint from that inner place. She was born into a highly religious and idealistic family, but one in which scandal tainted its ideals. Her grandfather, Theodore Tilton, was a newspaper editor in New York City and a protégé of the abolitionist and preacher Henry Ward Beecher. But Tilton’s wife, Elizabeth, had an affair with Beecher that brought public humiliation to her husband and led to the couple’s adult daughter Florence being sent to live in Germany.

In Stuttgart, Florence met William Halsey Pelton, a wealthy American expatriate from a Louisiana plantation family. Agnes was born to the couple in 1881 and lived in Europe until she was 7, when she and her mother moved to Brooklyn to live with Pelton’s grandmother. Agnes’ father, who led a dissolute lifestyle and had little involvement with his family, died in Louisiana of a morphine overdose when Agnes was 9. “Pelton’s background led her to revolt against organized religion and seek her own spiritual path, [that was] more personal and individualized,” Haskell says.

At age 14, Pelton began studying art at the Pratt Institute in Brooklyn, where one of her instructors was Arthur Wesley Dow. Dow later also taught Georgia O’Keeffe, six years younger than Pelton, and others who became early Modernists. His art philosophy was radical at the time, emphasizing the painter’s personal experience of color and composition rather than a straightforward illustrative approach. After Pratt, Pelton studied art for a year in Rome. Her early paintings reflected Dow’s perspective and that of the artist Arthur B. Davies, who depicted figures in romanticized wooded landscapes rich with symbolism.

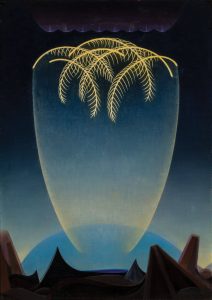

Messengers (Mensajeros) | Oil on Canvas | 28 x 20 inches | 1932 | Gift of The Melody S. Robidoux Foundation, 2014.39 | Courtesy of the Phoenix Art Museum

For Pelton, whose moody inner life was sometimes expressed in flowing, Greek toga-style clothing, this poetic inclination continued even as her work evolved along with her spiritual beliefs. For a time, she set up her studio in Greenwich Village and painted contemplative figures in pastoral scenes. But when her mother died in 1921, she left the city and stepped away from the New York art world. She moved into a converted historic windmill on Long Island, a space she described as a “mystical house, reaching into heaven and radiating from its center, distributing sustenance.”

At the same time, Pelton’s interest in mystical, esoteric forms of wisdom expanded to include a constellation of old and newly revisioned traditions. She began following Russian-American Helena Blavatsky’s theosophical teachings, which incorporated elements of Buddhism and Hinduism and was also interested in Rudolf Steiner’s anthroposophy and Agni Yoga. She established a personal meditation practice. Pelton was also strongly influenced by the work and writings of the Russian painter Wassily Kandinsky — himself a follower of theosophy — and by travels in Europe, Beirut, Syria, Hawaii, and elsewhere. All these aspects of Pelton’s spiritual quest translated into her art — an abstract visual language that began in the mid-1920s and continued throughout her life.

In 1928, Pelton traveled to Pasadena, California, to visit a group of like-minded spiritualists. Although she had spent a short time in the high desert of Northern New Mexico 10 years earlier on the invitation of the Taos-based art patron Mabel Dodge Luhan, that landscape did not capture her imagination as it did many other artists, including O’Keeffe. But the Southern California desert was another matter. Pelton returned in 1932, this time to the small community of Cathedral City near Palm Springs, thinking she would stay a year.

She never moved away. The expansive, stark emptiness and quality of desert light were the perfect context for the abstract imagery she used to express her inner world. As Pelton once said, “The vibration of this light, the spaciousness of these skies enthralled me. I knew there was a spirit in nature as in everything else, but here in the desert, it was an especially bright spirit.”

With several outward parallels in the lives of Pelton and O’Keeffe, the two artists have inevitably been compared. Before Pelton’s 1995 retrospective, “people talked about her as a second-rate O’Keeffe,” notes Vicario, who currently serves as chief curator at the Pérez Art Museum Miami in Florida. “O’Keeffe did an amazing job, but her practice was rooted in nature. She called a flower a flower and a hill a hill. Agnes was much more poetic. She saw beyond the visible world.”

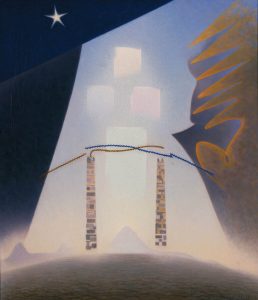

Future | Oil on Canvas | 36.18 x 24.18 inches | 1941 | Collection of Palm Springs Art Museum, 75th Anniversary | Gift of Gerald E. Buck in memory of Bente Buck, Best Friend and Life Companion

In another significant difference, while O’Keeffe was immersed in the New York art world and promoted by her husband, photographer and modern art advocate Alfred Stieglitz, Pelton supported herself solely through her art. When her work fell out of favor with museums, she lived frugally and painted desert landscapes to sell to tourists while pouring her soul into her work.

Pelton is associated with a small, relatively short-lived group of New Mexico-based painters who called themselves the Transcendental Painting Group. Their aim, like hers, was to “carry painting beyond the appearance of the physical world, through new concepts of space, color, light, and design, to imaginative realms that are idealistic and spiritual,” according to the group’s brochure for a 1939 exhibition.

One of the Transcendental Painting Group’s key artists, Raymond Jonson of Albuquerque, New Mexico, was familiar with Pelton’s work. He sent her letters “begging her to become honorary president of the Transcendental Group,” explains Vicario, to which Pelton reluctantly agreed. While her work was included in several of the group’s shows, she did not attend or travel to New Mexico beyond her early visit to Taos. Ten years Jonson’s senior, she was also much older than the other artists in the group. Pelton served as a role model and artistic inspiration, but she did not identify with their youthful energy, Zakian writes in his essay for a 1995 exhibition.

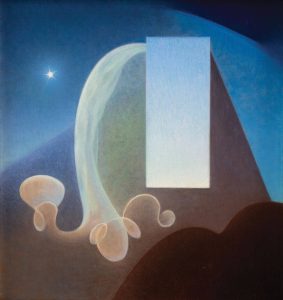

Many of Pelton’s works express life’s dichotomies with visual contrast — areas of light and dark, softness and sharp peaks, feelings of coolness and warmth. In her view, these differences represented the realm of the material world. It expressed the contrast between the difficulties of existence and the deeper energies of light, vibration, sound, and spiritual growth that lay beyond the physical.

Day (Día) | Oil on Canvas | 25.25 x 23.5 inches | 1935 | Gift of The Melody S. Robidoux Foundation, 2014.38 | Courtesy of the Phoenix Art Museum

In Pelton’s 1931 painting Ahmi in Egypt, for example, Haskell sees the figure of the swan as a self-portrait of the artist, standing beside a winding red river and dark landscape. Yet, emerging from that darkness and rising toward the top of the piece, “there’s a glorious flowering that represents enlightenment,” she says.

Among the paintings that inspired Vicario to organize the 2020 traveling exhibition was Messengers (Mensajeros), painted in 1932. The symmetrical image features a glowing vase-like form topped by gracefully curved palm fronds, rising from a dark, sharply craggy landscape. The often-recurring vase shape symbolized “comfort, containment, and security” for Pelton, writes Zakian in his essay.

Because Pelton was working through the decades of the Great Depression and World War II, Haskell believes her art reflects a response to the chaos and distress of the outer world at that time and an expression of her inner spiritual life. The curator sees a similar yearning in today’s world and, thus, a renewed resonance with Pelton’s art: “There’s a search for connection and meaning and something more personal and immaterial,” she says. Yet, because of the visually compelling nature of Pelton’s imagery, the viewer doesn’t need to know exactly what the artist was aiming to express, Haskell adds. “You really feel the quality of nature and the mystic quality in her work.”

Gussie Fauntleroy has written about art, architecture, design, and other subjects for almost 35 years. She’s the author of three books on visual artists and a senior contributing editor for Western Art & Architecture.

No Comments