15 Nov Perspective: R. Brownell McGrew [1916–1994]

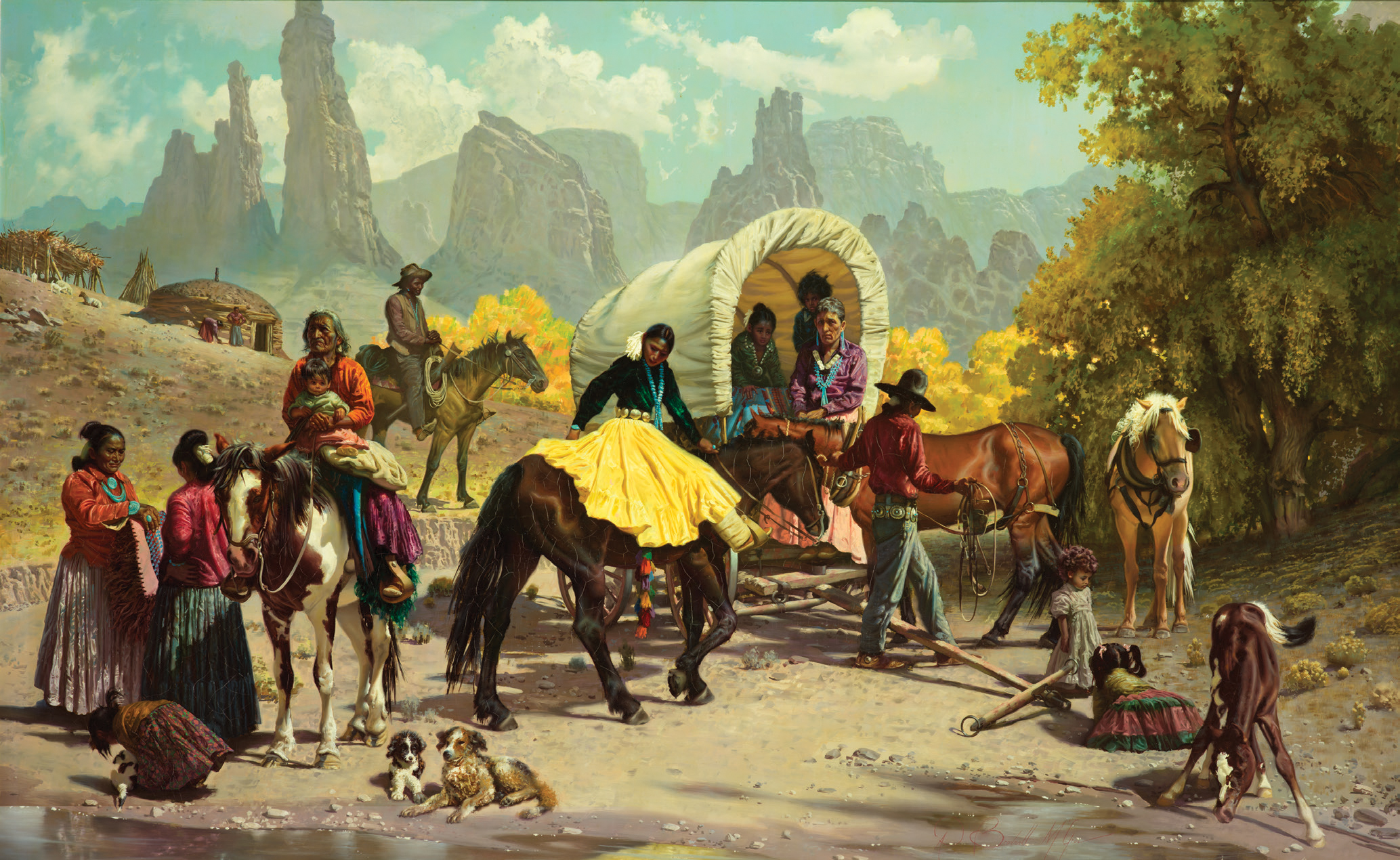

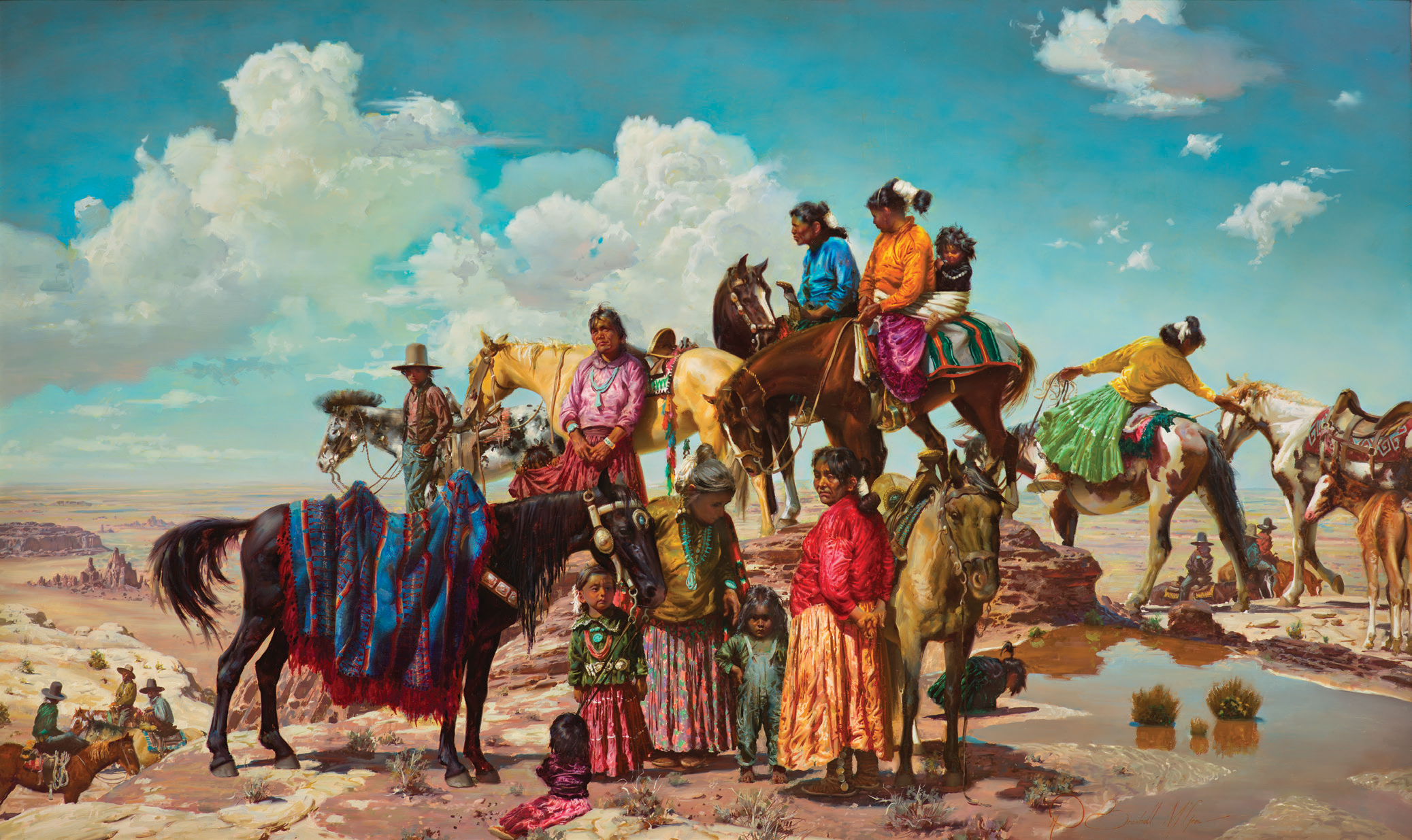

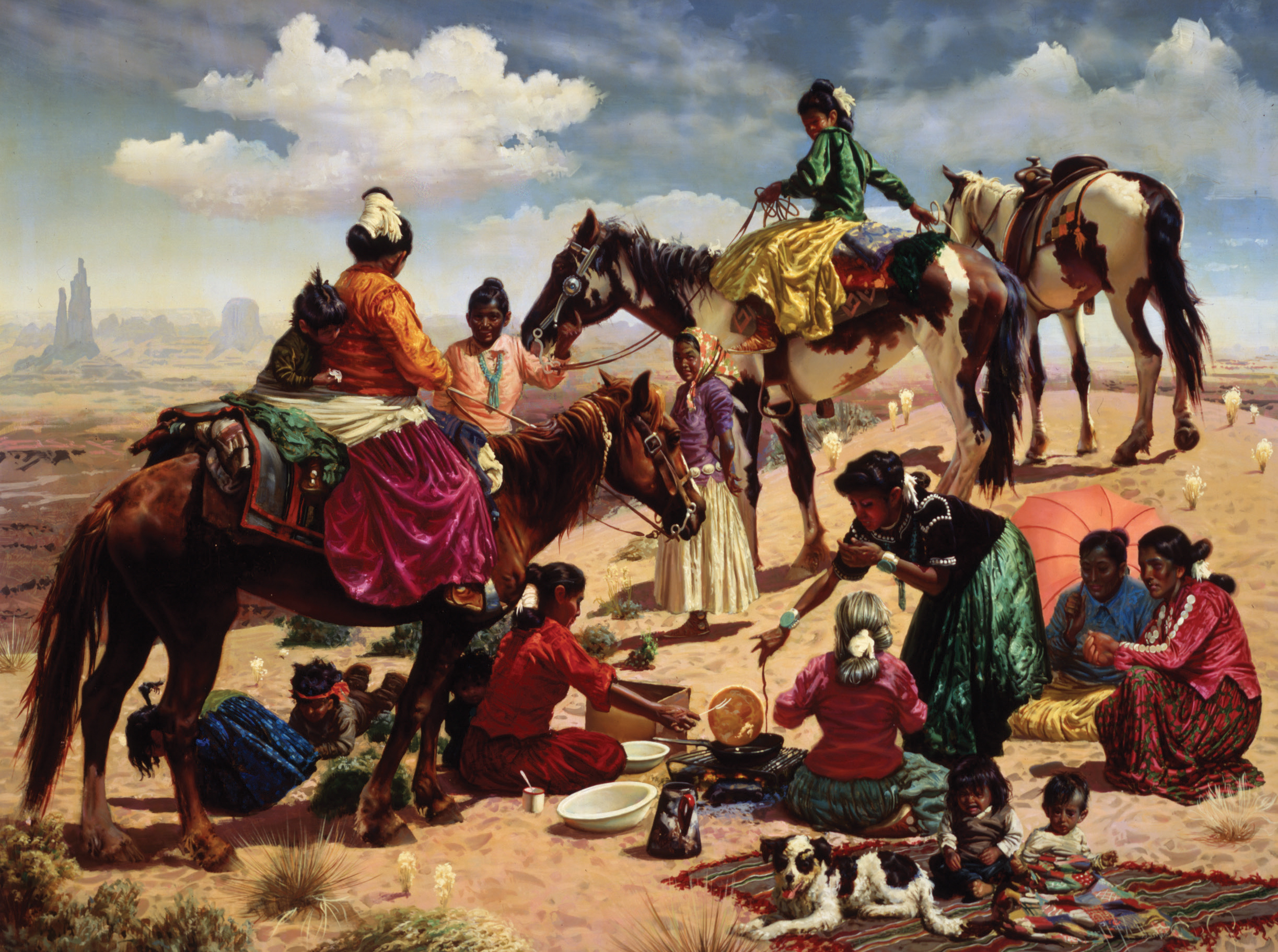

Ralph Brownell McGrew is considered by some to be one of the best Western portraitists of the 20th century. He painted portraits of the Diné (Navajo) and Hopi people of Arizona and New Mexico with such exceptional ability that his work is often said to appear three-dimensional. His canvases depict journeys on horseback and in covered wagons, daily tasks, and celebrated traditions amidst sun-splashed mesas and distant vistas. With colors that seem to jump from the canvas, his artwork tells a silent but poignant story of people dispossessed from their ancestral homelands, heritage, and independence, but not from their dignity.

Untitled | Oil on Masonite | Late 1930s – Early 1940s | Gift of Mr. Vernon W. Hillmer | Courtesy of the Autry Museum, Los Angeles; 2000.5.1

“He captured a particular time and place, and he had a special — and secret — technique that made his paintings look wet long after he completed them,” says Tricia Loscher, curator and assistant director at Western Spirit: Scottsdale’s Museum of the West. “That’s his legacy. He taught us how to see the Native peoples of the Southwest by sharing with us their souls.”

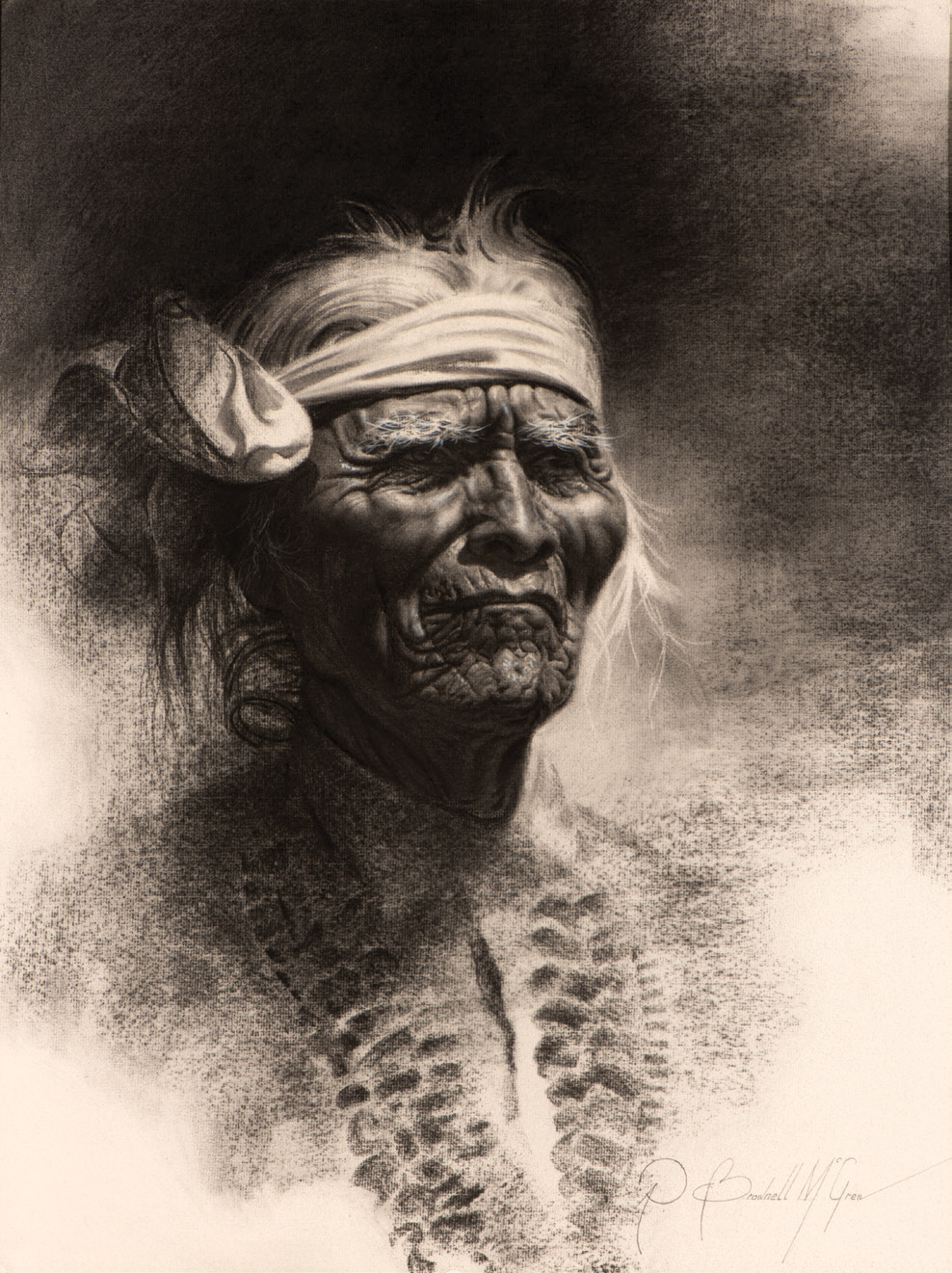

McGrew was trained in drafting and drawing, explains Elisa Phelps, vice president and chief curatorial officer at the Eiteljorg Museum. “That gave him a great eye for detail — reflected beautifully in his portraits of tribal elders — and an ability to create his work in a very distinctive way.”

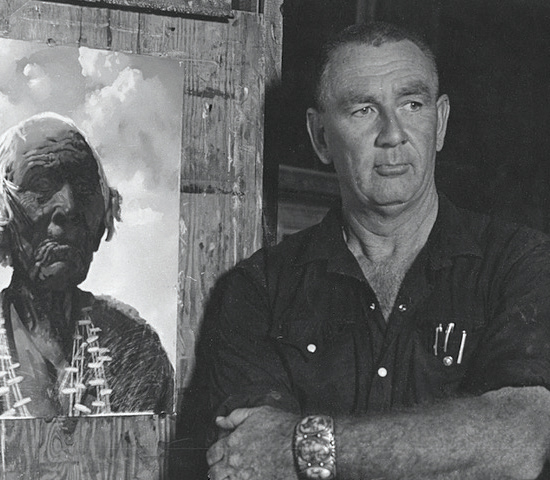

R. Brownell McGrew in his studio, c. 1984 | Photo courtesy of Gail Eifrig

The artist was born in 1916 in Ohio, and his family moved to California during his early teenage years. After studying at the Otis Art Institute in Los Angeles, he became a draftsman and designer for the Firestone Corporation and worked as a commercial artist for M.G.M. and Columbia studios before he discovered his love for painting the desert.

In 1946, McGrew became the first recipient of the John F. and Anna Lee Stacey Fellowship from the National Cowboy Hall of Fame in Oklahoma City, and he used the money to explore and study the Southwest. In the 1950s, he traveled and painted with Jimmy Swinnerton, who introduced him to the Diné and Hopi peoples of Northern Arizona. McGrew was instantly taken by the stark beauty of the landscape, by the ancient traditions still cherished, and by the people themselves. It changed his life forever.

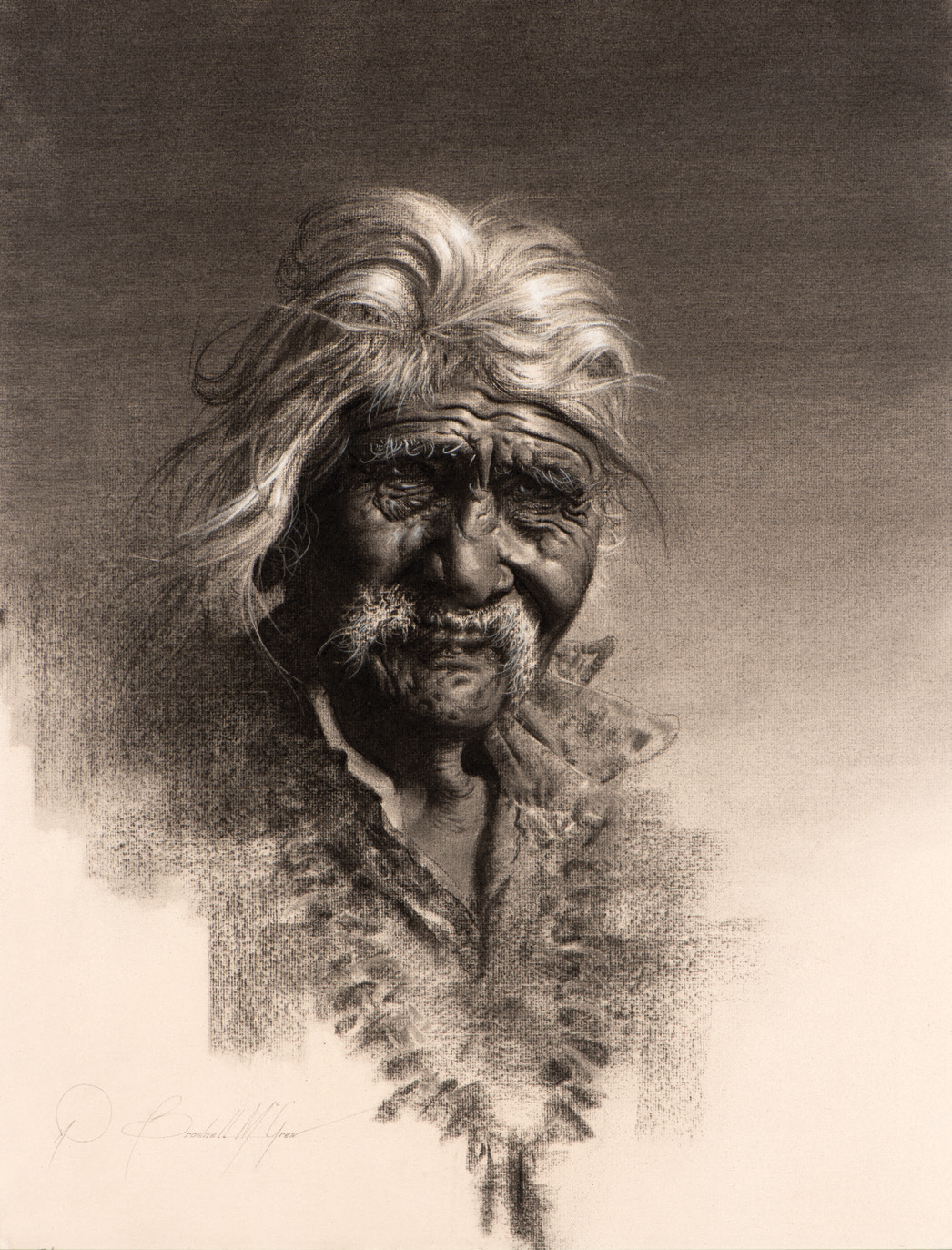

The Singer | Charcoal | 24 x 18 inches | Courtesy of the Eddie Basha Collection

“[American Indians] have a respect for nature and meet it on its own terms,” McGrew wrote in a letter now archived at the Heard Museum in Phoenix, Arizona. “We whites feel that we can manipulate nature to our own ends, and any landscape is a fitting subject for compulsive engineering.”

Soon McGrew became a familiar sight on the reservations. Initially people were somewhat uncomfortable with the idea of someone painting their picture, but as they got to know him, they eventually became comfortable enough to sit for portraits. Over time, McGrew became known among the tribes as “The Man Who Paints the Old.”

“My dad was a ‘starving artist’ for a while,” says Gail McGrew Eifrig, 79, the eldest of McGrew’s three daughters, all of whom live in Arizona. “Dad was more focused on his painting than on selling his paintings, and he took a long time to do each one. So our mom — who was very supportive of his work — began working to support the family, and we moved to Palm Springs in the late ‘40s so she could take a job as an executive secretary to the city manager.”

Pause on the Way to the Sing | Oil on Masonite | 1967 | Courtesy of The Anschutz Collection

McGrew’s reputation in the art world grew as his brilliantly-hued works drew attention both for his “pop out” technique — the secret of which he never divulged — and for his compelling imagery. “People who know and appreciate Western art, know and appreciate R. Brownell McGrew,” says Mario Nick Klimiades, director of the Billie Jane Baguley Library and Archives at the Heard Museum. “The people in his paintings often seem three-dimensional; they seem to almost pop off the canvas. And his works are hard to find, so I’ve often wondered why he actually isn’t more popular, and why the prices for his works aren’t higher.” Of late, McGrew’s paintings have sold in the $40,000 to $80,000 range.

Night Whiskers | Charcoal | 24 x 18 inches | Courtesy of the Eddie Basha Collection

“The first impression I had of McGrew’s work was a charcoal drawing he did for the CAA [Cowboy Artists of America] show,” says painter Martin Grelle. “And I was blown away. It was just so wonderfully executed. He captured perfectly the old man’s age, heritage, and character. I believe his way of painting with oils was pretty unique, especially for the Western art genre. He had more of an Old Masters’ technique, which gave his paintings a great luminosity and very brilliant color tones.”

McGrew was elected to the CAA in 1969 and became a charter member of the National Academy of Western Art at the National Cowboy Hall of Fame in 1973. In addition to his acclaim for painting portraits of tribal elders, McGrew also painted landscapes and family scenes from the reservation. One example is Going On A Visit, which depicts an extended family traveling on horseback and foot — little girls play in the dirt and grandmas sit in a wagon beneath a backdrop of craggy peaks and mesas. And Dolce Far Niente, Navajo Style depicts several men and women talking in the shade of a lean-to, with children and a baby in a papoose in the foreground.

Entaph, in the Cook Shade | Oil on Masonite | 1967 | Courtesy of The Anschutz

Variation on a Theme III | Oil on Masonite | 1973 | Courtesy of the National Cowboy & Western Heritage Museum, 1973.11.

“My dad eventually began getting commissions from magazines for his work, and that led to interest from museums and galleries,” says Eifrig. “But these people felt he should be charging much more for his work. So a gallery owner in Phoenix tripled the prices of his pieces, and they began selling like hotcakes. And one of his earliest buyers was Senator Barry Goldwater, who later ran for president.”

Tsinavinni Yazzie | Charcoal | 24 x 18 inches | 1974 | Courtesy of the Eddie Basha Collection | Winner of the 1974 Prix de West Gold Medal in Drawing at the National Cowboy & Western Heritage Museum

“My dad was a throwback,” Eifrig adds. “He was more concerned with quality than with money, which is why he only did a few paintings a year — although all the gallery owners begged him to do more. And, for each painting, he would do at least a hundred drawings of different elements he wanted to see in it.”

McGrew’s letters in the Heard Museum archives reveal much about the man. He once wrote, on hearing the sounds of Hopi priests singing in a ritual inside a kiva, that “There was something ineffably moving and primordial in the sound, carrying the mind back through the untold centuries, into the mists of time where the same deep, stirring tones called the ancestors of these and all men to look above and beyond themselves.”

No Comments