10 May Perspective: Rocky Mountain Rendezvous

Working on a commissioned portrait in his newlyopened New Orleans studio in early 1837, Alfred Jacob Miller looked up to see a handsome, well-dressed man enter the shop and watch quietly for a few moments as he painted. Miller may not have thought much of it at the time, but the stranger’s second visit a few days later would bring an offer of unimaginable adventure, chal-lenge, and opportunity that would reverberate through the rest of the artist’s life, career, and well beyond.

Miller was a 27-year-old European-trained painter who had recently moved to New Orleans from his home in Baltimore, hoping to establish a business in portrai-ture. The man who stepped into his studio, drawn by paintings displayed in the window, was Captain William Drummond Stewart, a son of Scottish nobility, retired from the British military, and a veteran of the campaign that defeated Napoleon at Waterloo. An adventurer 15 years older than Miller, Stewart had already traveled several times to America and the Rocky Mountain West.

Cavalcade (The Indian Procession) | Oil on Canvas | 69 x 96 inches | ca. 1839 | J. Joe Ricketts in association with the Ricketts Art Foundation

His offer to Miller: to accompany the captain and his party on an expedition to the Green River Valley in what is now Wyoming. Through sketches and paintings, Miller would document the rendezvous taking place there that summer. The rendezvous was a massive gathering of fur-trapping mountain men, Indigenous people from various tribes, and fur traders. At its peak from the mid-1820s to ’30s, the annual encampment brought together thousands of people and their horses. It was a combination of busi-ness, revelry, camaraderie, and relaxation before the par-ties went their separate ways.

Miller accepted the challenge.

He was not an outdoorsman and had never been far-ther west than New Orleans, but Stewart’s manner and broad experience clearly reassured him. As it turned out, Miller became the first and only painter of European descent to attend and document a rendezvous. And while art historians have long acknowledged that other early painters of the American West gave greater attention to detail and accuracy, Miller’s work is not only beautiful but also provides us with the sole first-hand visual account of this important and short-lived period in American history. While the artist only ventured West one time, he used his watercolor sketches as references for commissioned paint-ings for the rest of his career.

A current exhibition at the Buffalo Bill Center of the West in Cody, Wyoming, features more than 65 of Miller’s oil paintings, sketches, and small watercolors, many of them produced for Stewart. These were displayed in Murthly Castle, Stewart’s home in Scotland, and some were painted while Miller lived for a year at the castle in 1840. The artworks were sold and dispersed after Stewart’s death in 1871, with a number of them eventually return-ing to collectors and institutions in and around Wyoming.

Alfred Jacob Miller: Revisiting the Rendezvous in Scotland and Today represents the first time a significant number of works produced for Murthly Castle have been reassembled and considered together, along with a selection of artifacts from the fur trade era. The show runs through October 22 at the Center of the West and then travels to the Eiteljorg Museum of American Indians and Western Art in 2024. The exhibition has advanced scholarship on Miller, with new essays planned for publication in the Alfred Jacob Miller Online Catalogue. The catalogue, begun in 2015, is the most extensive online database of the artist’s Western paintings held in institutional collections.

Trappers Saluting the Wind River Mountains | Oil on Canvas | 21.938 x 35.813 inches | ca. 1864 | Buffalo Bill Center of the West, Cody, Wyoming. Gift of The Coe Foundation. 10.70

One important area of ongoing consideration is the influence of Miller’s European art training and cultural background on his perception and interpretation of the West. Born in Baltimore in 1810, he attended private school, likely received private art lessons, and in 1832 traveled to Paris to study art. He attended life-drawing classes at the École des Beaux-Arts and copied paintings at the Louvre. The following year he spent time in several Italian cities and then settled in Rome for more art stud-ies, returning to Baltimore in 1834.

He brought back with him an aesthetic inspired in particular by such painters as Eugène Delacroix, leader of the French Romantic art movement. Delacroix was known for his “intense color pal-ettes, expressive brushwork, dramatic and emotion-stirring subjects, and frequent focus on foreign peoples and places,” notes Karen Brooks McWhorter, Collier-Read Director of Curatorial, Education, and Museum Services at the Buffalo Bill Center of the West. McWhorter co-curat-ed the Rendezvous exhibition along with Johanna M. Blume, Curator of Western Art, History, and Culture at the Eiteljorg Museum.

Miller’s rendezvous imagery, espe-cially as it depicts Native Americans, was also heavily influenced by the prevailing Euro-American view of Indigenous people as “noble savages” and “uncivilized.” And there was another major factor in shaping his artis-tic choices: the captain’s position as patron and his own artistic goals. Stewart’s elder brother was seriously ill at the time, and Stewart would soon inherit his father’s estate and title as the seventh baronet of Murthly and attendant responsibilities. “He believed this would be his last trip West, so we have a significant understanding of his impe-tus for hiring Miller — that Stewart was memorializing this really important piece of his life and identity, and Miller was facilitating that,” Blume says.

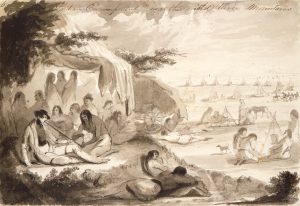

Indian Encampment Near the Wind River Mountains | Pencil with Black and Grey Washes on Paper | 6.375 x 9.5 inches | ca. 1837 | Buffalo Bill Center of the West, Cody, Wyoming. Bequest of Joseph M. Roebling. 15.80Foundation

During Miller’s stay at Murthly Castle, his letters home make it clear that Stewart visited the artist at his easel and made suggestions. In almost all of the paintings where individuals are recognizable, Stewart is prominent — a handsome, dashing figure in a tailored buckskin suit and flat-brimmed hat. Often, he is portrayed as an active ren-dezvous participant, smoking a pipe in social interaction with Native men or talking with trappers. “It’s like a fun ‘Where’s Waldo?’ search, looking for him,” McWhorter says.

Miller’s cultural biases as a 19th-century Euro-American male in situations that were completely foreign to him are especially evident in such works as Bartering for a Bride. (Other versions of the same event are titled The Trapper’s Bride. The artist produced multiple paintings from many of his watercolor sketches.) The scene depicts a trapper about to wed a Native American woman, a not-infrequent occur-rence among mountain men. Miller’s rendition contains Europeanized details designed to make the event more read-able to viewers and to fit his society’s values.

For instance, the bride is barefoot, echoing both the Romanticist style and the notion of a virginal bride, delicate and dependent on men. In reality, as scholar Dr. Kathleen Barlow has pointed out, the bride would have been wearing her best moccasins and leggings for such an important occasion. The painting’s composition and title also come from Miller’s misunderstanding of tribal customs. As revealed in his writings, he believed that the trapper was required to barter or pay for his bride. In fact, the gifts requested by the bride’s family were part of a complex reciprocal tribal practice of relationship building between family groups.

Bartering for a Bride | Oil on Canvas | 36 x 28 inches | 1845 | Courtesy of the Eiteljorg Museum of American Indians and Western Art, Indianapolis

Yet, regardless of the balance of accuracy and imagination in Miller’s Western art, the fact that he witnessed and painted the 1837 rendezvous provides a visual sense of things we oth-erwise would only know through writings — and some that would not have made it into words. It is widely acknowledged that another recognizable figure in many of the sketches and paintings is hunter Antoine Clement, Stewart’s lover.

Along with suggesting the existence of romantic involvement between two men, Blume points out that Miller’s paintings provide a clear counterpoint to the idea of rugged individualist masculinity among trappers and others in the early West. “In works depicting Stewart’s traveling party, I’m struck by a sense of ease and intimacy, a camaraderie between men in this group,” she says.

Historian Jim Hardee, editor of the Rocky Mountain Fur Trade Journal, served as an advisor on the selection and interpretation of artifacts in the exhibition. He explains that historians of material culture continue to examine Miller’s work for information on objects and activities too mundane to be described in journal entries, everyday things like the kettle hung over a fire. “It’s another piece of the puzzle,” Hardee says.

Antoine Watering Stewart’s Horse | Oil on Canvas | 30 x 36 inches | 1840 | American Heritage Center, Laramie, Wyoming. ah04912_005

Miller also captured scenes too extravagant for words. As Hardee explains, the 1837 gathering would have drawn as many as 2,500 people, along with 5,000 or more horses. The encampment beside the Green River would have extended 5 miles in either direction. Miller expressed the extraordinary scale and drama of the experience in the monumental-size painting Cavalcade. It depicts more than 1,000 mounted Shoshone encircling a camp in a grand parade-like entrance while the Wind River Mountains rise in the background. “It’s a jaw-dropping composition, a tour de force,” McWhorter says.

Indeed, critics have noted that despite the absence of finely rendered detail in many of the pieces and through Miller’s vagueness and loose brushwork, the viewer is offered the opportunity to imagine how it might feel to be part of the experience — the crowds, the dramatic hunt, and the quieter moments of rest or gathering around a fire. As McWhorter puts it, “There’s an emotional charge and sense of storytelling that might supersede fact.”

WA&A’s senior contributing editor Gussie Fauntleroy has written about art, architecture, design, and other subjects for 25 years. She’s the author of three books on visual artists.

No Comments