05 May Perspective: Standing the Test of Time

When the Fairmont Hotel in San Francisco was badly damaged by fire following the deadly earthquake of 1906, architect and engineer Julia Morgan was hired to design and oversee the building’s restoration. Known for her hands-on approach, the 34-year-old architect arrived early on the first day of construction. She was standing quietly, making notes, when a worker approached. “We’re waiting for the architect. Maybe best if you wait over there,” he said. Morgan looked up and responded, “I am the architect.” The man was sure she had misunderstood. “No, no, we’re waiting for the architect; his name is something like Joe Morgan,” he said, perhaps having noticed paperwork signed J. Morgan. She simply repeated, “I am the architect.”

Avery Morgan, Julia Morgan Standing on a Balcony in Paris | Cyanotype | 1899 | Courtesy of Morgan-Boutelle Collection, Special Collections and Archives, California Polytechnic State University

Architectural historian Mark Anthony Wilson, a professor at several Bay Area colleges, tells this story about a woman who designed more than 700 buildings, including Hearst Castle in California. During this extraordinarily prolific career, she certainly faced greater obstacles than condescending attitudes. But exceptional talent, hard work, and belief in herself carried her through the many challenges in what was then a nearly all-male field. And her finished projects spoke for themselves, winning her the respect of male peers and ultimately the highest honor bestowed by the American Institute of Architects. In 2014, almost 60 years after her death, she became the first female architect to win the AIA Gold Medal.

Painting of a French Chateau | Watercolor | ca. 1899–1901 | Julia Morgan Papers, Special Collections and Archives, California Polytechnic State University

The award was among the latest in a series of firsts for Morgan, starting with her achievement as the first woman admitted into the architecture program at the prestigious École Nationale Supérieure Des Beaux-Arts in Paris in 1898. In 1904 she was the first woman to obtain an architecture license in California, and she was a pioneer in designing with reinforced concrete for aesthetic as well as structural purposes. While her contemporaries were using the technology pragmatically for industrial buildings and infrastructure, she spotlighted both its earthquake-resistant properties and its beauty in residences and commercial projects.

Beauty and functionality, in fact, are central elements in all of Morgan’s buildings. “It’s hard to choose a favorite, which is an indication of her range of skills and the care and dedication she put into her buildings,” says Wilson, author of Julia Morgan: Architect of Beauty. “I’ve been in hundreds of them, and I’ve never been in one that wasn’t beautiful.”

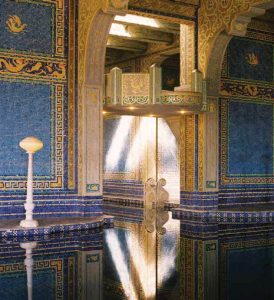

The Roman Pool at Hearst Castle was inspired by the mausoleum of Galla Placidia at Ravenna, Italy. It was designed with lapis lazuli tiles and gold leaf, assembled at Fugazi Hall in San Francisco, and shipped on pallets to San Simeon, California.

Born in 1872, Morgan came of age in circumstances that aligned with her interests and helped establish her career. Her mother, Eliza Parmelee Morgan, was the daughter of a highly successful cotton trader from whom she inherited substantial wealth. While Julia taught herself to live frugally and became known for completing projects within strict budgets, her family’s position granted her access to the upper echelon of society — and future clients — in Oakland, California, then a relatively small city.

Following the late Victorian era, American society began opening to progressive movements, including ever-greater numbers of women attending university and entering the workforce. Meanwhile, an expanding charitable landscape — schools, playgrounds, libraries, and social welfare programs — was spearheaded by women. “Morgan’s friends were frontrunners in that movement, and she was catching that wave,” says Karen McNeill, a historian who has been researching, writing, and speaking on Morgan for more than 20 years.

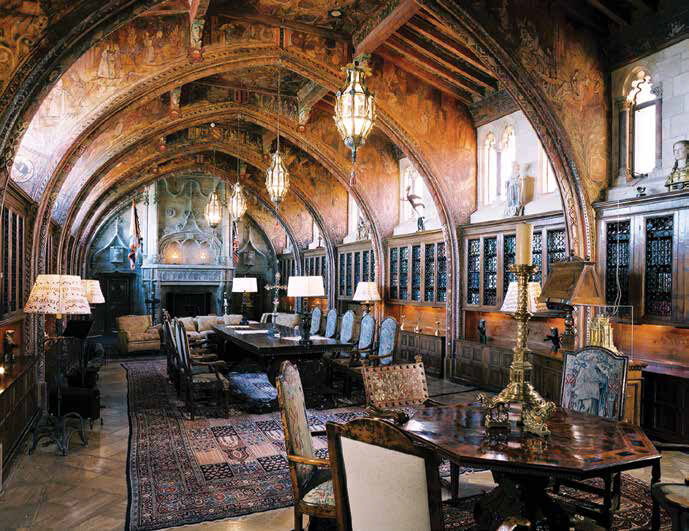

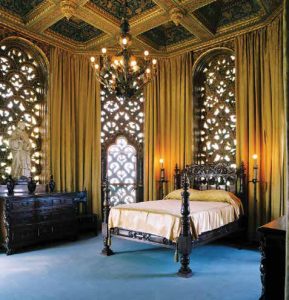

Morgan’s design of the main dining room at Hearst Castle — which William Randolph Hearst called the Refectory — is a collage of Gothic and Renaissance elements. It contains 14th-century Spanish choir stalls, Palio di Siena flags from Tuscany, Italy, and 27-foot walls topped with a flat Renaissance ceiling rather than an arched Gothic one.

Morgan herself was supported in her desire for higher education by her family and by noted architect Pierre LeBrun, her second cousin’s husband, whom she’d known since childhood. She enrolled at the University of California in Berkeley, but since it had no architecture program, she studied civil engineering. Often the only woman in her math, science, and engineering classes, she graduated in 1894. One instructor, in particular, turned out to be a highly significant figure in Morgan’s life and career. Architect Bernard Maybeck became a mentor, privately tutoring her and a handful of others, and encouraging Morgan to seek entrance into l’École Des Beaux-Arts, which Maybeck had attended.

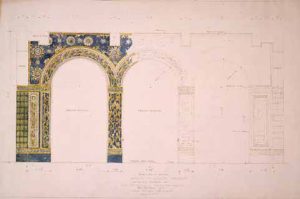

A sketch of the elaborate mosaic on a loggia, or porch, inside Hearst Castle. The estate was designed by Morgan from 1919 to 1947 and is known for its opulence. Courtesy of Julia Morgan Papers, Special Collections and Archives, California Polytechnic State University.

Arriving in Paris in 1896, Morgan initially lived at the American Club for Girls, where she met female architects Katharine Budd and Fay Kellogg. She also spent time with members of the Union of Women Artists and Sculptors and was inspired by their feminist ideas. Among these was the belief that women should have access to the examination process for admittance into l’École Des Beaux-Arts. In 1897 the school bowed to pressure from the union and others and, for the first time, opened the exams, including architecture, to women.

While most published information on Morgan states that she passed the entrance examination on her third attempt, McNeill’s research reveals she sat for the exam four times. (McNeill’s findings are presented in the newly published anthology, Julia Morgan: The Road to San Simeon, Visionary Architect of the California Renaissance.) On the fourth try, after intensive tutoring under Prix de Rome-winning French architect François-Benjamin Chaussemiche, she passed. Most students graduated in five or six years; she finished in two-and-a-half years.

The Celestial Bedroom, in the south tower at Hearst Castle, was established by raising the bell towers. As a result, the footprint was no bigger than the original towers, leaving no room for a closet or bathroom. This page: Doge’s Suite, a bedroom in Hearst Castle, features a painted Dutch ceiling formerly located in architect Stanford White’s home in New York. The room, whose name is from a 15th-century Venetian balcony, was an especially coveted room to be assigned to guests. It was completed in 1926 and remodeled in 1931. Photos: Joel Puliatti

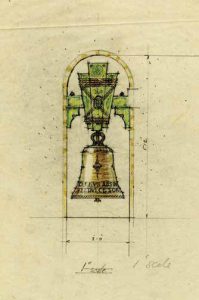

After working briefly for another architect, Morgan opened her own firm in San Francisco in 1904. That spring, she completed the 72-foot reinforced concrete bell tower, El Campanil, at Mills College. Borrowing from California mission architecture, the handsome, five-story tower is topped by a red clay tiled gable roof, with arched openings for its 10 bronze bells. Two years after the tower’s completion, Morgan’s design and choice of materials faced the ultimate test during the 1906 earthquake. It survived undamaged. “With El Campanil, she was so innovative because she saw potential for beautiful things in the plasticity of concrete,” McNeill says. In an earthquake-prone region, the project immediately enhanced her reputation and career.

Morgan went on to design six more structures at Mills College. (One was not completed.) Her interest in advancing opportunities for young women also led to a long affiliation with the Young Women’s Christian Association (YWCA), for which she designed dozens of projects. Among the best known is the Asilomar Conference Center in Pacific Grove, now part of the California State Park system. The complex stands out for the architect’s relatively restrained approach to Arts and Crafts and First Bay Tradition styles — extensive use of redwood and stone and wide but not dramatic overhanging eaves — and for the thoughtful placement of buildings within the landscape.

Morgan was hired to restore the iconic San Francisco Fairmont Hotel after an earthquake in 1906. Photographed by Charles Weidner (ca. 1906) Courtesy of Julia Morgan Papers, Special Collections and Archives, California Polytechnic State University.

Morgan’s design for the Gum Moon Methodist Chinese Mission School (1909–1911) in San Francisco reveals another critical skill: She was a master at designing on a budget without sacrificing beauty or essential elements. In the project, she used inexpensive methods to suggest cultural references, including red brick construction and green paint for the window and cornice trims, two important colors in Chinese culture. Then she could be more exuberant in select areas such as the entrance, with a painted iris decoration as the archway keystone and a Chinese lantern and tiles inside the arch. Morgan also saved money by using open wooden trusses and other exposed framing as striking aesthetic elements. Quoting Maybeck’s phrase, “an open use of natural materials, honestly stated,” Wilson sees this as an admirable quality in Morgan’s work as well.

If Morgan is known for one thing, it’s her almost 30-year collaboration with William Randolph Hearst and his family on the design and construction of Hearst Castle. The relationship began early in her career when Hearst’s mother, Phoebe Apperson Hearst, commissioned her to remodel a hacienda in Pleasanton, California. In 1919 the newspaper magnate hired Morgan to design La Cuesta Encantada, later called Hearst Castle, on a hillside overlooking San Simeon Harbor. The Hearst affiliation expanded over the years to include designing multiple structures, grounds, and pools at the estate, as well as dozens of other buildings around California and in Mexico. With each project, Morgan was deeply involved in virtually every detail. She assimilated Hearst’s collection of art and antiquities into the buildings, worked with him to find architectural elements and objects from Europe, supervised construction, and personally oversaw purchases — while also designing buildings for multiple other clients.

The legendary landmark sits atop Nob Hill with panoramic views of the city and bay. Photographer unknown (ca. 1906) Courtesy of Sara Holmes Boutelle Papers, Special Collections and Archives, California Polytechnic State University.

Hearst Castle’s major structures and their adornments reflect a blend of styles: Spanish Renaissance, French Gothic, Ancient Roman, and others, including original artifacts and reproduced motifs. The effect is what Jennifer Shields, associate professor of architecture at California Polytechnic State University in San Luis Obispo, refers to as “architectural collage.”

For decades Morgan’s significance was downplayed because she did not develop a singular style. In recent years, however, architectural historians and authors have begun to acknowledge the brilliance behind her work. Shields, the author of the book Collage and Architecture, uses the term collage with respect, especially as it reflects Morgan’s skills as a consummate listener and collaborator. She designed exactly what clients wanted — aesthetically, spatially, functionally, and within their budget — rather than focusing on her own legacy.

A one-inch to-scale drawing of a bell designed by Morgan. Courtesy of Julia Morgan Papers, Special Collections and Archives, California Polytechnic State University.

Yet, her legacy is significant. With the 150th anniversary of her birth this year, Morgan’s achievements are being celebrated more than ever. In early 2022 Shields curated an exhibition, Julia Morgan, Architect: Challenging Convention, at Cal Poly’s University Art Gallery. It featured a selection of the architect’s original drawings, photographs, and correspondence. And adding to the growing number of books on the architect are the newly published Julia Morgan: An Intimate Biography of the Trailblazing Architect, by Victoria Kastner, and Drawing Outside the Lines: A Julia Morgan Novel, by Susan Austin. “I’m always meeting architects, engineers, and designers who love and find her inspirational,” McNeill says. “Not necessarily as a stylist, but as a person.”

WA&A’s senior contributing editor Gussie Fauntleroy has written about art, architecture, design, and other subjects for 25 years. She’s the author of three books on visual artists.

No Comments