06 Sep Perspective: The Wilderness in Watercolor

One morning in 1923, Swedish-American painter Gunnar Mauritz Widforss was having breakfast in Camp Curry at Yosemite National Park when Park Service Director Stephen Mather asked if he could join him. Mather was out of uniform, as was his custom, so he could solicit honest feedback from park visitors on their experience, as the National Park Service had only been established in 1916. Widforss, a genial, soft-spoken but outgoing man, welcomed the stranger to his table, and they struck up a conversation. It couldn’t have taken long for each to figure out who the other was: Widforss, an exceptionally talented watercolor landscape artist who was creating breathtaking paintings of Yosemite’s iconic landforms; and Mather, the man in charge of marketing and selling the national park experience to the public.

Gunnar Widforss painting at Asilomar State Beach in 1926. Photo: Albert Derome

“You can see a light bulb go off over each man’s head,” says Alan Petersen, curator of fine arts at the Museum of Northern Arizona in Flagstaff. Mather would have thought, “This is who I need to sell the parks!” And a dollar sign would have lit up over Widforss’ head. “This is what I need to sell my art!” Indeed, the meeting and friendship that developed between Mather and Widforss proved highly beneficial for both parties.

In the years before the artist’s untimely death at 55 in 1934 from a heart condition, Widforss became known as the Painter of the National Parks. After Yosemite, he painted and lived at the Grand Canyon. He produced images that were used on postcards and menus at both parks, and his paintings were reproduced on magazine covers and sold at the gallery inside El Tovar Hotel on the Grand Canyon’s South Rim.

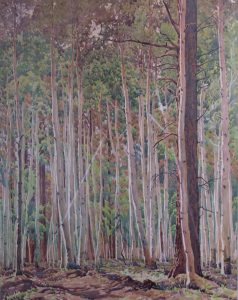

Aspens | Watercolor on Paper | Size and Date Unknown

With the Museum of Northern Arizona housing the largest collection of Widforss’ art, Petersen has done extensive research on the painter. He has published a Widforss catalogue raisonné, on view at gunnarwidforss.org, and is currently writing a monograph. He says that although public familiarity with the artist diminished after World War II, contemporary landscape painters and collectors are increasingly coming to know and admire his work.

In this growing circle, Widforss is recognized as “one the finest watercolor landscape artists of the 20th century who depicted the American West,” says longtime gallerist Richard Lampert, co-owner of Zaplin Lampert Gallery in Santa Fe, New Mexico. “While very much appreciated by those who know his art, Widforss is still under the radar. His works don’t come our way as often as we would like.”

Born in Stockholm, Sweden, in 1879, Widforss was one of 13 children of Mauritz Widforss and Blenda Carolina Weydenhayn. His mother was a skilled painter who studied at Konstfack University College of Arts, Crafts, and Design in Stockholm, then known as the Technical Institute. Gunnar entered the same school at age 16. His father was a businessman with a hunting apparel and firearms shop. Both parents were supportive of their son’s interest in art; Gunnar’s father periodically sent funds when his son ran out. The painter was good at making money but less skillful at managing it, Petersen says.

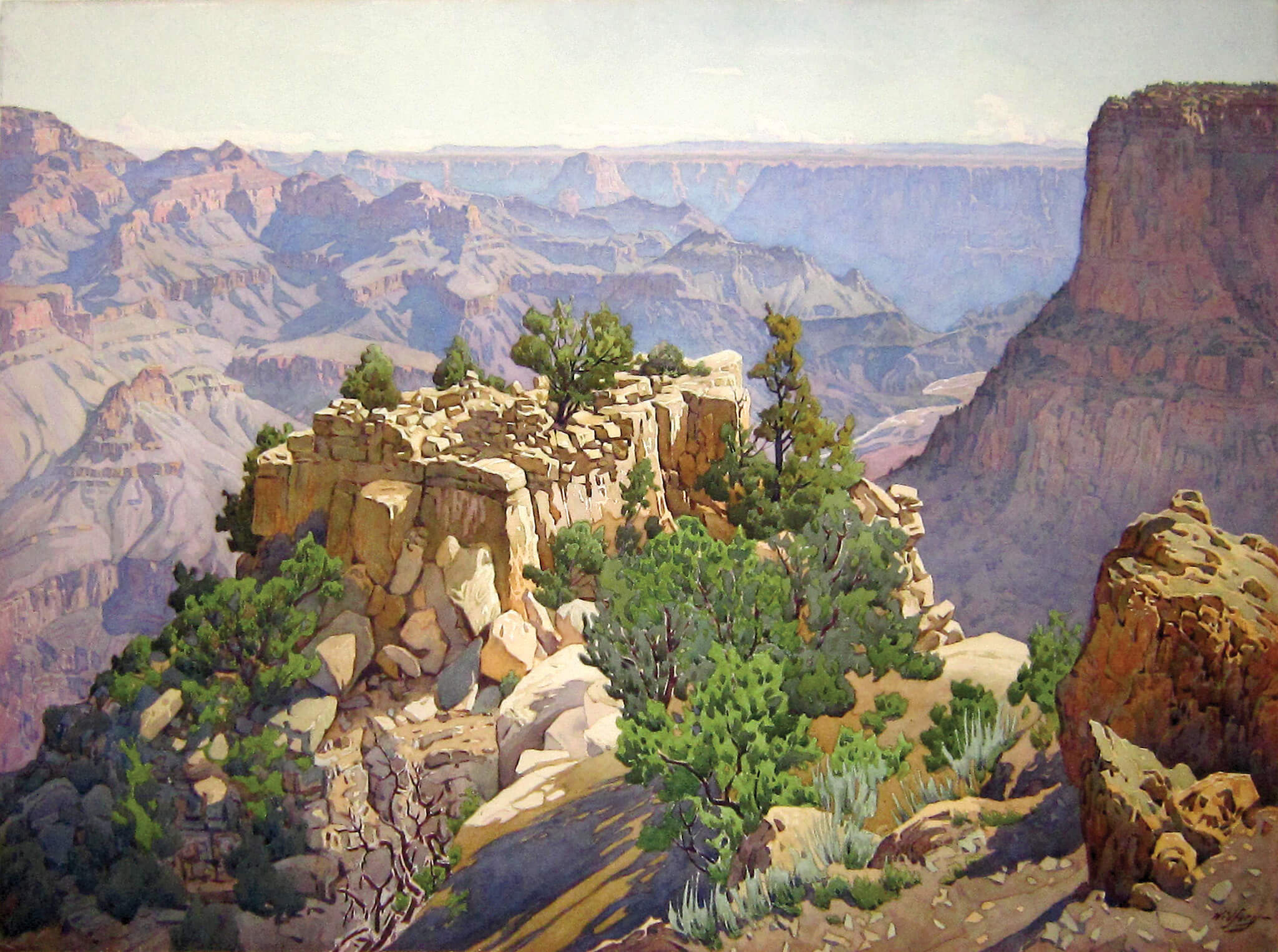

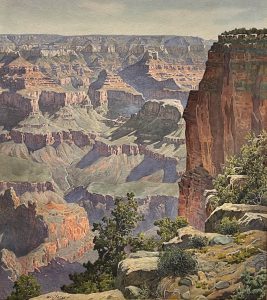

Plateau Point, Grand Canyon | Watercolor | 20 x 25 inches | c. 1930

Following graduation from the Technical Institute, where he learned such crafts as faux finishes and mural painting, Widforss moved to St. Petersburg, Russia, to apprentice in decorative painting. But he did not enjoy the work, finding it oppressive and uncreative. Back in Stockholm, he briefly set up shop as a decorative painter, probably to please his father. Within a year, he had dropped the venture and begun traveling around Europe, searching for beautiful places to paint. Between 1904 and 1909, he spent time on the French Riviera, in Italy, Austria, Switzerland, and North Africa, often setting up his easel in spa towns where tourists could watch him produce paintings and then buy them. By his second trip to America — he lived briefly in Florida and New York in 1906 — he had gained considerable technical skill in painting the landscape. He arrived in California in 1921 and soon headed for Yosemite, where two years later he met Mather, and his relationship with the national parks began. He also traveled periodically to California’s coast and exhibited at galleries in Carmel-by-the-Sea and San Francisco.

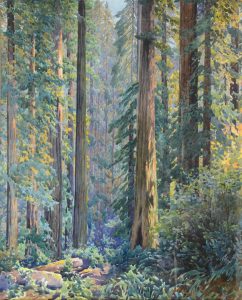

Redwoods | Watercolor on Paper | 24.625 x 19 inches | c. 1926

In 1923, Widforss made his first visit to the Grand Canyon. As Petersen suggests, “Yosemite had been a big challenge — there was no landscape just like it in Europe. But Gunnar was always up for a challenge. So, when he saw the Grand Canyon, it was like: ‘Okay, here’s this!’ And of course, he totally nailed it.” Unlike most Grand Canyon artists, Widforss’ first attempt at painting the vast, complicated vista spread before him was not limited to a side canyon or a single promontory; rather, he produced a panorama of a classic view from the North Rim. “He dove in from the deep end,” Petersen says.

Widforss was unlike other plein air painters in another way as well. He generally did not complete a piece in one sitting. The painting Plateau Point involved returning to the same location 10 days in a row at the same time of day, and each session meant a 12-mile round-trip hike deep into the Canyon. Already in his mid-40s and despite being a heavy smoker and drinker, “he was very energetic and active,” Petersen says. The artist’s demanding work habits and prolific output — his relatively short career produced some 4,500 paintings — left little time for romance, although there are hints at a relationship with Grace Watkins, who ran the gallery at El Tovar Hotel.

What drove Widforss as much as his pure enjoyment of painting and desire for self-challenge was a profound connection with the natural world, a value he shared with his Swedish contemporaries. In conveying nature’s essence, he offers an awe-inspiring experience to those who view his work, Petersen says. “He was able to not just capture the light in the scene he’s painting, but through his technique, he was able to create a radiance, to have the painting emanate the light.”

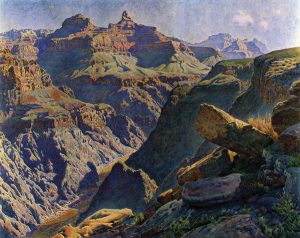

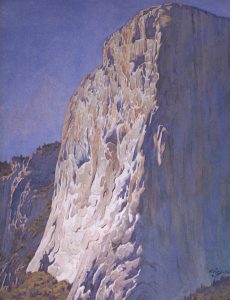

Grand Canyon | Watercolor on Paper | 19.5 x 17.5 inches | c. 1926

While most watercolor artists paint wet-on-wet in washes, Widforss applied short strokes of relatively thick, transparent color. This way he could work in an arid climate, proceeding methodically as the paint dried. Glen Knowles, a present-day watercolor artist and drawing and painting professor at Antelope Valley College in Lancaster, California, has studied Widforss’ paintings. Along with extraordinary drawing skills and mastery of value, what stands out for Knowles is the artist’s use of color. Many landscape painters enhance color, but Widforss honored what he observed. “Most colors in nature are muted,” Knowles says. “Widforss’ color is truthful. His watercolors are tapestries of muted colors woven together to create a symphony of nature’s very essence.”

But there’s something else, and it has to do with how the human eye sees. As we scan a scene, our eyes are continually making micro-adjustments to the light. Our pupils open and close quickly in infinitesimal degrees to allow us to refocus and perceive details simultaneously inside shadows and in bright light. The camera doesn’t do this. With much landscape painting, details in the shadows are minimized in favor of simpler, dark, often graphic shapes. In Widforss’ work, on the other hand, we view details in shadowed areas and in full light. “Just as our eyes do,” Knowles says. “The result is we have this visceral experience of being there looking over the artist’s shoulder at the actual scene. That’s what people have always responded to in his work, his extraordinary realism that makes us feel like we are there in the presence of nature as he was painting, and now as we view his watercolors 100 years later.”

Yosemite, Nocturne | Watercolor on Paper | 17.25 x 12.25 inches | 1922

Most widely known during the 1920s and ’30s, Widforss received his first museum exhibition at the National Gallery of Art in Washington, D.C., in 1924, followed by two exhibits at the Brooklyn Museum of Art in the late 1920s. Yet while he enjoyed a niche market for a time, he was swimming against the tide of Modernism. Movements including Regionalism, Abstract Expressionism, and even the California Watercolor Society artists, who were inclined toward abstracted forms and brilliant colors, were heading in new directions. “He was old-fashioned,” Petersen says, “but he was content with what he was doing.”

Now the tide is turning again, and Widforss is becoming better known and celebrated, especially among contemporary landscape painters, including such acclaimed artists as Merrill Mahaffey and Ed Mell, who point to his work as highly inspirational. Knowles, also powerfully moved by Widforss’ art, recalls visiting the painter’s gravesite at the Grand Canyon Pioneer Cemetery. “You encounter a very emotional tribute,” he says. “A number of artists have made that same pilgrimage and planted an artist’s brush in the ground, bristle-side up, on top of his grave. It feels like the image of medieval knights laying down their swords, honoring their fallen king.”

No Comments