07 Nov Perspective: Western at Heart

There’s a story that art historian Michael R. Grauer tells about two co-founders of the Taos Society of Artists, the small group of painters who, beginning in 1915, were highly influential in popularizing realistic and romanticized images of the American Southwest. The first time William Herbert “Buck” Dunton and Oscar Berninghaus went camping in the mountains above Taos, New Mexico, St. Louis-bred Berninghaus took along a silk-covered pillow. Dunton soon convinced his fellow painter to leave such nonessentials at home.

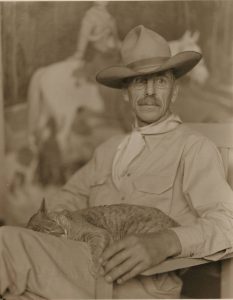

W.H. Buck Dunton, Taos, New Mexico | Photographed by Will Connell, 1932 | Courtesy of the Palace of the Governors Photo Archives (Negative Number 059756)

Grauer calls the tale a “rural legend” (as opposed to urban legend), meaning that although its veracity is unconfirmed, it says something true about the two men. Born and raised in Maine, Dunton was much more of a true outdoorsman than most of the other Taos Society artists. He was exceptionally skilled at hunting and comfortable among those Western men he called “old timers.”

Dunton stood apart in other ways as well. There are varying opinions on whether he moved to Taos in 1914 or 1915. But after living for a few years near Taos Plaza, he settled into a home farther from the small community’s central square where the other painters had their homes and studios, and where they socialized together and brought in Taos Pueblo Indians and other models to paint. More significantly, in the decades since he died in 1936, Dunton has received far less attention as an individual artist than such Taos Society artists as Berninghaus, Joseph H. Sharp, E. Irving Couse, or Ernest Blumenschein, even though he was an equally talented painter. The last major exhibition featuring his art occurred more than 30 years ago.

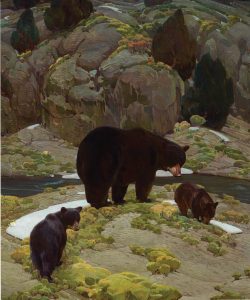

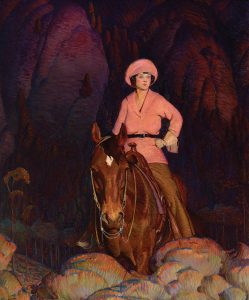

Mountain Mother | Oil on Canvas | 60 x 50 inches | c. 1932 | Bequest of Nelda C. Stark, 1999, Stark Museum of Art, Orange, Texas, 31.21.410

An exhibition at the Phoenix Art Museum through June 2024 aims to restore Dunton to his rightful place among the Taos artists — and, more generally, as a painter of the American West. William Herbert “Buck” Dunton: A Mainer Goes West brings together some of his most significant works, while a companion show features works by other Taos Society artists. Organized by the Phoenix Art Museum and the Harwood Museum of Art in Taos, A Mainer Goes West allows visitors to see “what a deft and talented painter Dunton was, which may be a surprise to some because his work is not so readily seen in many places,” says Michael K. Komanecky, independent curator and art historian, who co-curated the exhibition with the museum’s adjunct curator, Betsy Fahlman and Nicole Dial-Kay, the Harwood Museum’s curator of exhibitions and collections.

The show’s concept arose when Komanecky was chief curator for the Farnsworth Art Museum in Rockland, Maine. Researching Dunton’s origins in that state, he first presented his findings to fellow art scholars at a conference in Taos. Fahlman, a former colleague at the Phoenix Art Museum, shared her enthusiasm and helped the exhibition come to fruition in Phoenix and Taos.

Dunton was born in 1878 and grew up on a farm near Augusta, Maine. As Komanecky points out in an essay for the show catalogue, the wilds of that state’s vast forests had a profound, lifelong impact on the artist and helped prepare him for his time out West. As a boy, Bert, as his family called him, spent many summer days with his grandfather in the woods, learning to hunt and fish. His grandfather instilled in him the importance of humane hunting. Throughout his life, Dunton believed one should never attempt to hunt before becoming very precise with a rifle, and never kill more than one needs.

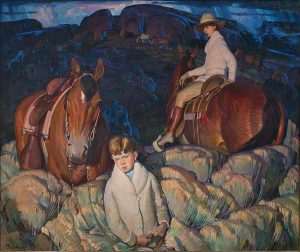

My Children | Oil on Canvas | 50 x 60 inches | c. 1922 | Collection of the New Mexico Museum of Art. Gift of a friend, 1927 (351.23P). Photo by Blair Clark

Stories of cowboys, grizzlies, and Native Americans in popular magazines of the day fueled Dunton’s early fascination with the West. He later wrote that, inspired by these stories, he and his friends called each other “pard” and “began to slink about the pasture in wide-brimmed hats, our belts bristling with discarded pistols, and butcher knives borrowed from the kitchen.”

In the summer of 1896, when he was 18, Dunton first visited the West. “He threw a few things in a bag, picked up his old Winchester, and took the train as far West as it would go to Broken Bow, Nebraska,” says Grauer, adding that from there, he traveled on to Livingston, Montana, probably by stagecoach or wagon.

Having studied Dunton’s life and art since 1989, Grauer is the foremost living authority on the artist and is working on a Dunton catalogue raisonné. To date, he has catalogued some 1,300 works. Grauer currently serves as McCasland Chair of Cowboy Culture and Curator of Cowboy Collections and Western Art at the National Cowboy & Western Heritage Museum in Oklahoma City.

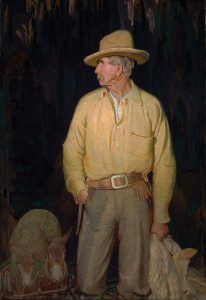

McMullin, Guide | Oil on Canvas | 60 x 56 inches | c. 1934 | Bequest of H.J. Lutcher Stark, 1965, Stark Museum of Art, Orange, Texas, | 1.21.22231.21.410

Dunton dreamed of becoming a cowboy, but once he was in the West, he discovered he was no good at it. In a 1924 magazine article, he poked fun at his ineptitude: “Though I had lots of experience, I made a sorry [cowboy] … Why! even to this day, I couldn’t rope a sick chicken with his legs hobbled.” What he could do was hunt, and over the next 15 summers, he traveled to Mexico and the West — to Montana, Wyoming, Colorado, Oregon, and New Mexico — hiring himself out to ranches to provide game for feeding the cowboys, and drawing and painting his observations.

When not in the West, Dunton studied art in Boston and New York City, and his long, highly successful illustration career flourished. Over the years, he created countless illustrations, often of Western subjects with sketches made from life, for magazines including Harper’s Weekly, Collier’s, Woman’s Home Companion, Scribner’s, and Cosmopolitan. He illustrated numerous books, including Zane Grey’s Western tales. His art was also accepted into major exhibitions at such institutions as the Academy of Design in New York, the Art Institute of Chicago, and the 1924 Venice Biennale.

In 1912, Dunton was studying with the painter Ernest Blumenschein at New York’s Art Students League when Blumenschein suggested he visit Taos. He went that summer and fell in love with the landscape, the clear light, and the feeling of a place where ancient Indigenous cultures and Old West ways had not yet been replaced by modern life. Soon after, he left New Jersey, and Taos became a substantial part of his life.

Ginger | Oil on Canvas | 50.813 x 33.875 inches | c. 1932 | Gift of Vivian Dunton, Harwood Museum of Art of the University of New Mexico, 1980.245

There, he helped found the Taos Society of Artists, whose primary purpose was to sell their art by organizing traveling exhibitions around the country. Frequently seen wearing a 10-gallon hat, Dunton found great satisfaction in painting the landscape, cowboys (including Mexican vaqueros), Native American subjects, and iconic figures of the West. One of his primary goals was to capture what he saw as a quickly vanishing era. Grauer speculates that Dunton gave himself the nickname “Buck” as more befitting his identity as a Westerner.

His wife Nellie, however, was not as taken with the Old West — electricity wouldn’t arrive in Taos until 1928 — and the couple divorced in 1920. Grauer believes they lived separately for most of their married life; Nellie and their two children periodically visited Taos, and Dunton returned to the family home in New Jersey. A 1922 painting titled My Children depicts the artist’s daughter and son looking melancholy with their horses against a dark background amid rabbitbrush outside Taos.

Such portraits represent one of four distinct stylistic phases in Dunton’s art that Grauer sees. First was his prolific illustration work. Among New York publishers in the early 1900s, he was considered “the only true successor to Remington,” Grauer says. When Fredric Remington died shortly after receiving a significant commission from Cosmopolitan, Dunton was selected to complete the commission.

While he continued to accept illustration commissions until about 1923, after moving to Taos, he was eager to shed his reputation as an illustrator and encouraged magazine writers to describe him as a plein air painter. He also befriended the Russian painter Leon Gaspard in Taos and briefly experimented with more expressive brushstrokes and heavier textures. After resigning from the Taos Society of Artists in 1922, for unclear reasons that likely involved oversized egos among the group, his approach shifted again.

Romaldita | Oil on Canvas | 30 x 25 inches | c. 1922 | Bequest of Nelda C. Stark, 1999, Stark Museum of Art, Orange, Texas, 31.21.401

This is the striking style of his portraits: dark backgrounds and dramatic frontal lighting reminiscent of a stage set. Forms are somewhat simplified, with an emphasis on curvilinear shapes. In this style Dunton portrayed his children and iconic Westerners, including the hunting guide depicted in McMullin, Guide. Grauer sees this phase of Dunton’s work as suggestive of American Regionalism of the early 1930s, as expressed by such artists as Grant Wood, Thomas Hart Benton, and Alexandre Hogue.

Indeed, while Dunton is often pigeonholed as a Taos Society artist, his legacy reaches beyond the Taos group. “He was an Old West artist, too. He had a foot in each camp,” Grauer says, adding that Dunton deserves to be remembered among the generation after Charlie Russell, along with Frank Tenney Johnson, Maynard Dixon, and Edward Borein.

As for Dunton himself, he had his own notion of how he wanted to be remembered. In a 1914 interview in the New York Herald, he remarked, “What I want is to paint for the connoisseurs, yet have the people out ‘in God’s country’ say, ‘That man’s been there.’”

Gussie Fauntleroy has written about art, architecture, design, and other subjects for almost 35 years. She’s the author of three books on visual artists and a senior contributing editor for Western Art & Architecture.

No Comments